It’s hard to believe. We are only an hour from the urban mayhem of New York City and there is no sound but birdsong and the burble of a trout stream. It’s as if the outside world is walled off by a curtain of streamside shade trees.

The yellow line whips vividly from Cole Baldino’s five-weight fly rod. We are calf-deep in the cool, tannin-tinted water of New Jersey’s Musconetcong River, a tributary of the Delaware. Baldino is Delaware River Coordinator for Trout Unlimited.

The Musky is a lovely stream, protected under the federal Wild & Scenic River Act. There are hatchery-supported brown and rainbow trout and the occasional brookie. But Cole’s eyes light up when he discusses another fish, not a trout at all.

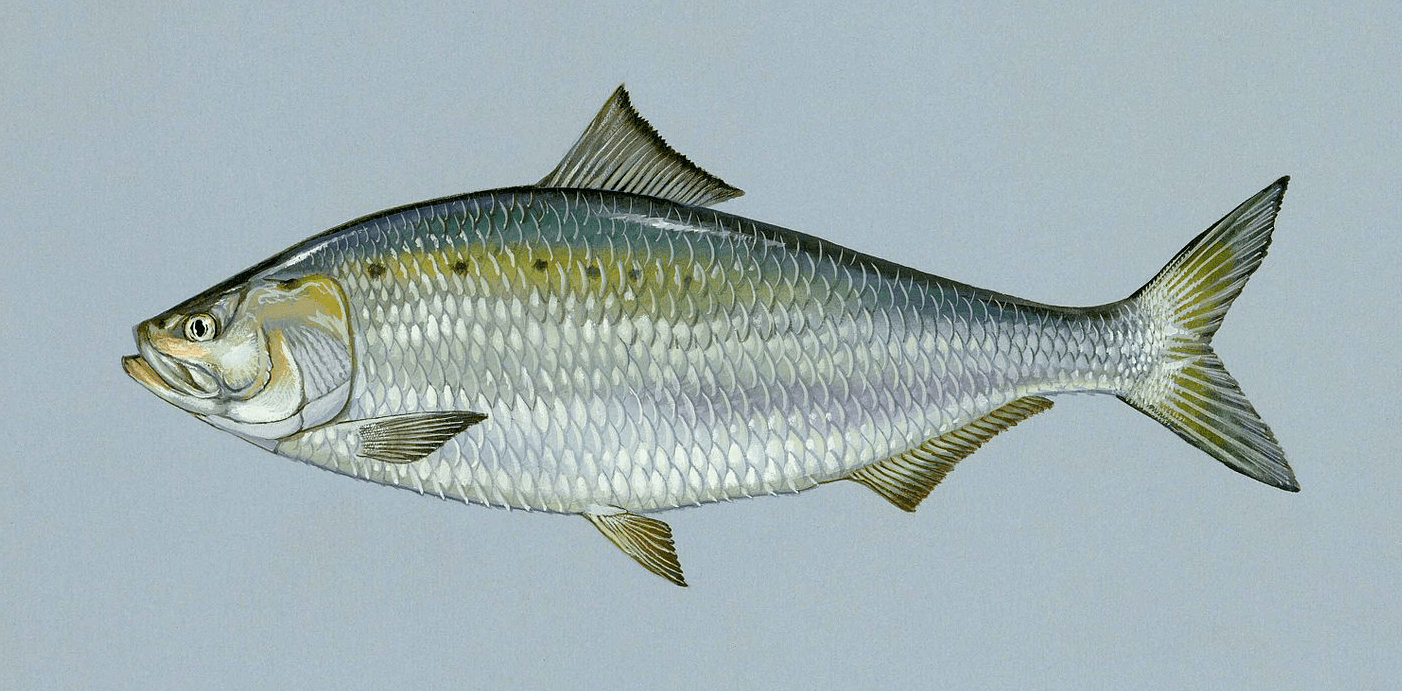

“They are about this big,” holding his hands about 16 inches apart, “and they are really fun to fish for. They are silver with two black dots on the side near the head. They are basically a big, anadromous herring.”

Baldino is talking about American shad. When I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, “anadromous” described steelhead and chinook salmon that return to mountain spawning streams after reaching adulthood in the ocean.

Turns out shad in the mid-Atlantic states share a lifestyle. Or at least they used to. Like salmon, the downfall of shad has been dams. But compared to the giant dams of the Columbia Basin, those on the Musconetcong are much smaller and much older.

The Musky dams date back 200 years. As early as the Revolutionary War, owners of sawmills and flour mills took advantage of any drop in the river to turn a water-wheel. The resulting dams, though no more than 32 feet high, are plenty big enough to block the sea-run migrations of shad.

“Shad had not migrated into the Musconetcong since the days when George Washington’s Army marched through,” Baldino says. “But they are coming back.”

Times have changed in the New Jersey Highlands. The small manufacturing plants that once dotted the river have long been replaced by urban factories. Eighteen dams remain on the main stem of the Musky. Some are critically important, but others are obsolete, increasingly at risk of failure and hazardous for boaters and children playing in the river.

Cole has teamed up with other conservationists and community members to gradually remove unneeded dams. So far, about six of the Musky’s 48 miles have been reconnected with the ocean.

“The removals are a huge victory,” he says. “But the return of shad in one year of the removal is just immense. The spawning habitat is in great shape, and the shad returned completely on their own once adequate habitat was open. It goes to show how effective dam removal is.”

As evening fades, I recall the familiar equation: Habitat + Access = Opportunity. Give nature a chance and she will produce. Even in the shadow of New York City.