LYING THERE on our bellies, we could stare over the brink of the precipice and figure how long it would take a boulder, pried loose from the top, to reach the sink of the valley below. Several seconds, probably. Through our 6X binoculars we watched an osprey hover over the wind-scuffed waters of Last Man Lake, then power-dive and come up with what looked like a half-pound rainbow trout in its claws. Without the binoculars we couldn’t see the fish hawk at all. That’s how high we were.

Northward, the 10,500-foot spire of Mount Tatlow seemed almost within hand touch. But that was only a trick of the clear altitude to which our goat had led us; Tatlow was a full 10 miles away as the crow flies.

Yes, we could see many things from the sheer spine of the cliff, things both near and far, but we could not see the goat. I wasn’t surprised, for I had never expected we would. “Bit exasperating, isn’t it?” The Englishman had rolled over and now lay on his back, propped on his elbows. The remark came in his usual good-natured Oxford accent but I knew it barely covered the frustration that was eating him. And there was sound reason for that frustration. Three days in a row we had come out after the old man of the cliff, and three times in a row he had eluded us. We had yet to fire a shot.

Yes, we could see many things from the sheer spine of the cliff, things both near and far, but we could not see the goat. I wasn’t surprised, for I had never expected we would.

At first we tried to take him from below. I should have known better, for previous experience there in the Chilcotin district of British Columbia had taught me that not often will a goat be taken from below. But we tried it—zigzagged up from the valley floor until we stood at the base of the palisade upon which the goat bedded. From its shale-littered base it reared 2,500 feet above us, its wall as vertical as that of a skyscraper and made almost as smooth by centuries of spring run-offs and autumnal winds.

About halfway up the palisade the goat stared down from its precarious perch on a ledge.

Next we tried an approach from the east, more wishfully than wisely. Since there was a half-mile strip of shale that somehow had to be crossed in full view of the goat before we could get within even doubtful range, our effort was barren of result.

On the morning of this third day we’d left camp with the intention of climbing to the top of the mountain and working around until we were immediately above the goat. For me the spark of hope burned mighty low, for I judged that the ledge upon which the goat slept was a good 1,000 feet below the top. And I doubted that we’d be able to see it from above.

But the Englishman was stubborn and determined, so we sweated, puffed, and cursed our way up the mountain-again to taste the bitter fruit of defeat. I studied this scion of the British aristocracy whose weightiest concern at the moment was to get within range of an old billy goat. His 6-foot 1½-inch frame toted 170 pounds of healthy flesh and muscle. And he was no novice in the trickier, finer points of big-game stalking. I wasn’t surprised to learn he’d been to the Austrian Alps for chamois, which are almost as elusive, he told me, as our own Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep.

Half-heartedly now I said, “We could settle for some other goat.”

The retort bounced back like a rifle shot: “And admit the beast has us whipped? No. We’ll not break off the engagement this early.”

That was the heart of the matter. The British will not recognize defeat even when it laps at the shores of their isle. Being English-born myself I can speak with some authority.

At the outset he hadn’t wanted a second goat trophy any more than I wanted the sword Excalibur. He’d crossed an ocean and a continent for just one thing: a bighorn ram with horns no less than 40 inches in curl and 15 around the base. He’d hired me for a 28-day hunt and we’d spent seven of the days in getting his trophy. On our 10th day a single 180-grain bullet from his .303 British rifle got him a mountain goat with black, tapering prongs that were 9¾ inches long. I told him that by law he was entitled to another but he shrugged it off.

Neither was he interested in mule deer, moose, or bear. So with our thoughts on fishing, we had dropped back down into the valleys and pitched camp on the north shore of Last Man Lake, whose trout are totally uncivilized and strike at anything remotely resembling a fly.

Across the lake, on the southern shore, the cliff reared abruptly toward the September sky. And the goat was there on its face when we moved in to set up camp. Out of habit I uncased my binoculars and focused them on the cliff. “An old buster,” I said aloud. “Horns run maybe 10 inches or better.”

“What sort of fly shall we use?” asked the Englishman.

“Fly?” I echoed. “Shucks, they’ll swallow a naked hook.”

The sun had set and shadows enveloped the rock when the goat got up out of his bed on the sheer cliff. For several seconds he stood like a statue, peering down at our camp. Then he slowly descended the rock and disappeared into a small patch of junipers 300 feet below his bed.

By sunup next morning he was back in the bed, and in the clear morning light my binoculars revealed how he had reached that ledge on the cliff. From the juniper patch a narrow ribbon of trail ran up to the ledge and then corkscrewed crazily skyward, branching out like a three-tined pitchfork where the west contour of the rock wall met a drab shale slide. The mere thought of any living thing moving to and fro over such a dubious footpath chilled me.

The Englishman squinted up at the cliff and observed, “Bit inaccessible, isn’t he?” That was putting it mildly. Then he added, “Just how would we tackle the job of taking him?”

That’s when I blundered. “Impossible!” I blurted out.

The Englishman’s eyebrows went up. “Impossible?” There was a challenge in his voice if I ever heard one.

But it was too late to retreat. “As long as he stays on that ledge by day,” I said, “and feeds and waters in the juniper by night, he’s as safe as a hibernating groundhog.”

For the next 10 minutes the Englishman was silent as his glasses raked the cliff. Then they dropped to the juniper patch and held steady. “Yes,” I heard him say. “There’s a rill in the brush.” By “rill” he meant a spring. He dropped his glasses to to his chest and said, “Y’know, he presents a bit of a problem, but I think it’s one we might solve. Anyway, we’re going to try.”

You couldn’t argue with that tone of voice…

WE WERE AT the top of the cliff. At first it seemed physically impossible to descend the chimney which rose from the juniper patch where the goat fed and watered. At its top the chimney was a mere fissure in the cliff but it widened out, funnellike, as it dropped. We had inspected the chimney earlier in the day and decided that even if one could climb clear down it to the junipers, no useful purpose would be served. The feeding habits of the goat were as punctual as the chimes of Big Ben; when he moved off the cliff and into the junipers it was far too dark to see through any type of sight.

Now we came back to the rim of the chimney and stopped. The Englishman examined it again and said thoughtfully, “There’s a foothold here, another one there. All in all, I’d wager a £5 note I could get down the blessed thing and into the brush.”

“It’s possible,” I conceded. Then bleakly I reminded him, “Suppose you do, and see the goat on the cliff. Suppose he’s in range. What happens when you shoot? He goes off that rock into space, and by the time we catch up to him at the bottom there’s devil a splinter of horn left. You’d be risking neck or limb for a trophy you wouldn’t take home.”

The Englishman’s steady gaze made me uneasy. After a moment he said, “He won’t be on the ledge if and when I shoot. He’ll be down in the junipers.”

This was getting silly, so I said tartly, “Never in daylight will he be in the junipers.”

“He hasn’t been so far. But supposing someone moved down along that cliff trail above his bed?” The Englishman’s eyes quizzed mine, and now the pattern of his plan took bold, definite shape.

SLOWLY I SAID, “You mean someone traveling the face of that cliff from top to bottom?”

“There’s no other way,” he said simply.

I buttocked down onto the cold ground, sudden weakness in my knees. Making an effort to keep my voice steady I said, “Go on.”

The Englishman took a .303 cartridge from his pocket and traced a line in the shale. “Right here,” he said, “the trail leaves the junipers. And here”—the shell formed a circle—“is the bed. Here”—continuing the single line—“the trail leaves the ledge and climbs the rock wall.” With the shell he traced two lines branching from the single one. “Here are the forks on the slide. We can’t do anything with them, even if we could induce the old gentleman to go up there. So he’s got to come down to the junipers.”

As simple as that! “Who,” I demanded, “is going to send him down?”

“You.”

I! I come around the face of that cliff on a trail that only a mountain sheep, goat, or little red fox would dare travel! I, who dreaded high places.

I picked up that fear as an 11-year-old boy in rural England. At the time the collecting of birds’ eggs was a highly important matter to me, and I’d discovered the nest of a kestrel hawk some 60 feet up on the branches of an old elm that boasted very few limbs on the first 50 feet of its trunk. By swarming up a few feet here and clinging to a dead snag there, I was almost within reach of the nest when the branch on which I was perched snapped with a sickening crack. I was left dangling in space, unable to go higher, fearful of trying to move down.

I soon realized I had to do something, so I began sliding down the trunk. Twenty-five feet from the ground I twisted my head and looked below. I sickened with fear, my arms and legs became numb, I lost my grip, and I fell.

I came out of that deal with a fractured shoulder, two broken ribs, and a badly wrenched ankle. My hurts healed quickly but the psychological wound never did. Today, 40 years later, I’m still unable to look over the edge of a precipice or crag without experiencing the same sickening of the stomach I felt as I clung to the elm.

Apart from the highly questionable matter of my ability to navigate the trail, there was a certain soundness to the Englishman’s plan. With care, he might well be able to descend the chimney. And the hint of danger from above should send the goat right down into the ambush.

But the trail! A writhing eight-inchwide thread nicking the face of the cliff. Sheer perpendicular rock above, sheer perpendicular rock below. And never a tree limb or tuft of grass on which to get a handhold. I wanted to shout, “No—not for all the goats in these hills!”

The Englishman’s eyes were still on mine. “Well?” he said.

“Too late this afternoon,” I replied. He nodded. “But if he’s still there in the morning?”

“Let us cross that one when we come to it.”

THERE WAS STILL a chance—an honorable avenue of escape. The goat might be gone from the face of the cliff by the dawn of another day.

In the morning we sat by the campfire, dawdling over coffee, waiting for the mist to clear in the valley. I was nibbling furiously at my fingernails when the sun broke through and the dark face of the rock slowly took shape. As I found it in my glasses I muffled a deep sigh. There on the ledge, in bold relief against the somber background, was a single blob of white…

I hunkered back on my heels and watched the Englishman start down the chimney. There was nothing easy about his end of the bargain. It called for iron muscles, steady nerves, and only a passing acquaintance with the word fear. Slowly, as if he were being lowered on a rope, he slid down the crevasse, his hands groping cautiously for cracks or outcroppings that offered holds for hand or foot. I waited at the top until he dropped out of the mouth of the funnel and, with a wave of the hand, melted into the junipers.

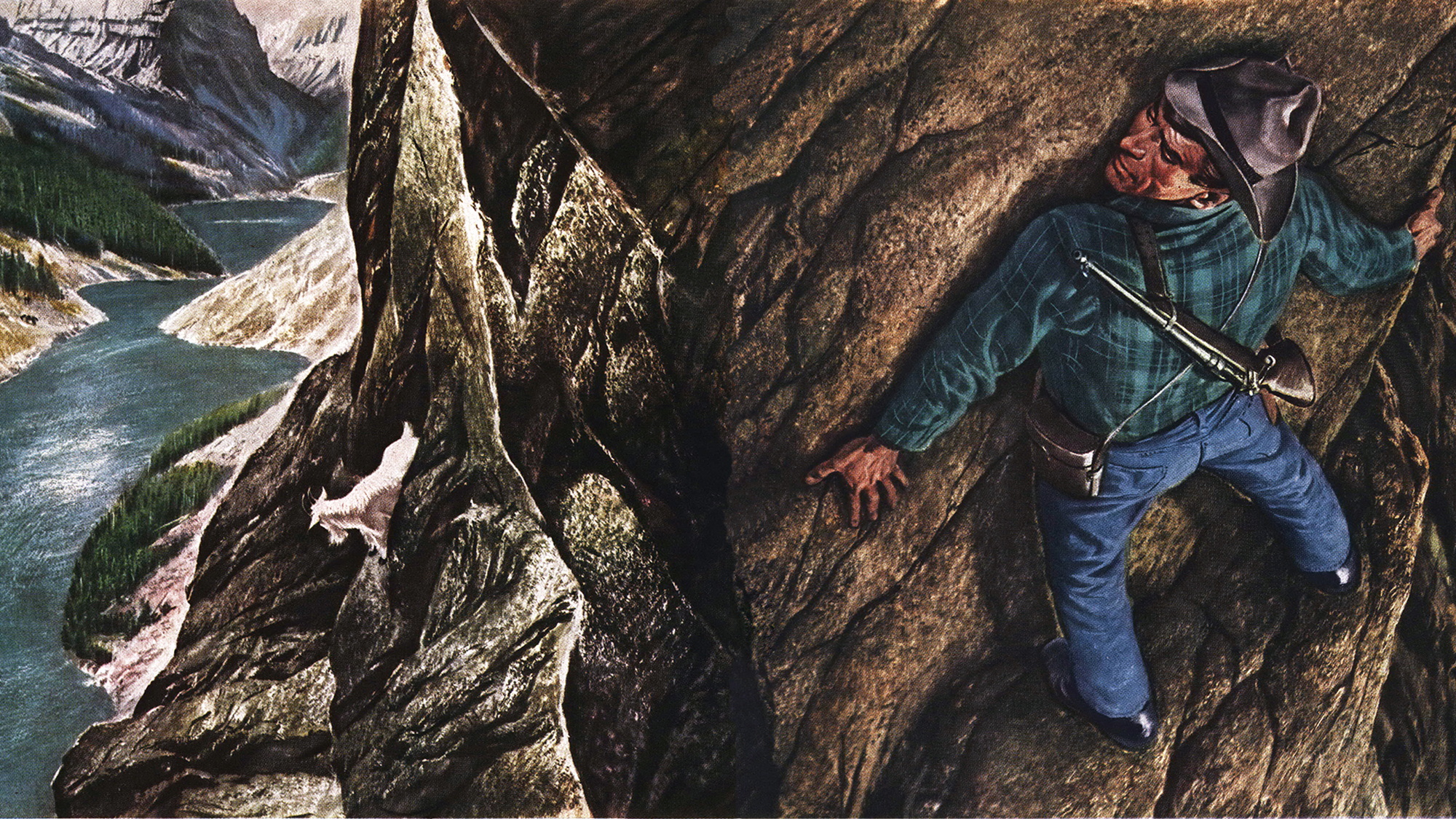

Then I got up, hitched the sling of my .303 Ross tightly over my shoulder, and moved flaggingly along the skyline.

I wanted badly to flash just one quick downward glance, to find a landmark that might give me a clue as to how much of my hellish journey still lay ahead. But I resisted stubbornly and kept my eyes on the wall.

That morning the wind was out of the north and it was erratic, now barely rustling the stalks of alpine weeds, now coming with a force that sent clouds of granulated shale billowing away. With each sudden blast I paused, listening. Down on the face of the cliff it seemed that a thousand doors banged shut each time the wind flailed that solid, impregnable barrier.

The rimrock petered out and I moved onto the shale slide. Though tilted at an angle of 70° or 80° there was nothing challenging about it, for it was littered with rock fragments that offered plenty of handholds and footholds. I’d been up and down a hundred similar slides in the years I’d been hunting big game.

Now I moved onto the trail that formed the upper tine of the fork and drew steadily nearer the rock wall where the goat had his bed. I hoped—almost prayed—that for the next 15 or 20 minutes the spasmodic bursts of wind would be held on leash. Fifteen or 20 minutes, I kept telling myself—that’s all the time the job should take.

Then the three prongs met and I was on the main trail. I could no longer see the sun—the cliffside hid it. A sudden rush of wind pressed me against the wall, and I flattened there, waiting for a lull. I didn’t dare move until the wind subsided.

Suddenly I was beset by an urge to glance downward, to look at the tents across the lake. But I fought the temptation. I must not look below, for just a glance would nauseate the stomach, buckle the legs, almost shut off the air from my lungs. Look above or ahead—yes. Below, never.

The wind died down. With my outstretched hand palming the rock wall I moved forward. Shut off from the sun I should have felt cold there on the cliff, but beads of sweat formed on my forehead and my underclothes were clammy against my skin.

A new thought rose to torment me. What if the goat should decide to come up that trail? Then he and I would face each other in a spot where neither could turn back. Huddled against the rock I gingerly unslung my rifle and bolted a cartridge into its chamber. Then, having doubly checked the safety, I reshouldered the rifle and inched forward.

I gained considerably more footage before another rush of wind plastered me against the cliff. Again a magnet was plucking at my eyes, trying to draw them below. I wanted badly to flash just one quick downward glance, to find a landmark that might give me a clue as to how much of my hellish journey still lay ahead. But I resisted stubbornly and kept my eyes on the wall.

Then I was tempted from a new side. Why go onward another step? Why not shout now? Surely the goat would hear me, even though I was above him and a considerable distance away. He’d hear me and move down into the sights of the Englishman’s rifle. Then I could turn back and claw my way to the top.

AGAIN I FOUGHT TEMPTATION. I was a guide, accepting good money from a hunter. He, in return, had every right to expect that I’d leave nothing to chance. The acoustical qualities of a mountain of solid rock are unpredictable. If I shouted now, the goat would hear me. But could he determine where the shout came from? Wasn’t there a chance that instead of going down he might come up?

I couldn’t do a halfway job; I had to keep moving down the trail until I was close enough to the billy to leave him no alternative but to go down.

For the next three minutes the wind pinned me motionless on the ledge. Then, as suddenly as it had come, it subsided. I was able to move again. I found that by taking short, quick steps I could balance myself far more easily than by sliding along like a snail. I was wearing rubbers over Indian moccasins and they gripped the rock firmly.

Between the goat’s bed and the prong trails, I knew, the ledge made three separate loops around as many shoulders of rock. I’d got around two of them and the third was directly ahead. I moved nearer to it, then halted. If the goat had not moved from his bed I was now within 100 yards of him.

Suddenly I was beset by an urge to glance downward, to look at the tents across the lake. But I fought the temptation. I must not look below, for just a glance would nauseate the stomach, buckle the legs, almost shut off the air from my lungs. Look above or ahead—yes. Below, never.

A large fragment of slide rock lay across the trail and I toed it off into space. I could hear it strike the cliff again and again as it hurtled toward the bottom, and I listened intently. From far to the north, somewhere around Tatlow’s snow-capped spire, came the muted drone of the wind. There was no other sound save the beating of my heart.

Somehow I dreaded rounding that final loop to see the goat ahead of me. There is a belief among the Chilcotin Indians—maybe it’s a superstition—that when a mountain goat is cornered on one of his trails he fears neither man nor beast, and will butt either over the edge. True or not, I now had no choice. So I filled my lungs with air and roared, “Look out below!”

I heard the faint tinkle of rocks on the cliff, then the unmistakable thud of hoofs. To me, sweating it out on the ledge, time seemed immeasurable. But perhaps only a minute passed before I heard the muffled roar of the Englishman’s rifle. One, two, three quick shots—the volley you hear when someone is shooting at a fast-moving target. Now, for the first time since leaving the slide, I dared a glance below.

I saw the frothing waters of the lake, the tents on the farther shore, the dark mass of spruce girdling its marge. How many times in the past had I cursed windfalls? How many times had I fretted at the density of brush as I circled the tracks of a buck? Now that timber seemed a friendly haven where one could move from tree to tree without care where one placed one’s feet.

I rounded the final loop and stared down at the juniper patch. I could see the goat, lying on its side, and the Englishman standing over it. He glanced up at me, waved, and called, “Well done.” I shrugged the rifle into a more comfortable position and edged down the trail to join him.

This story, Flesh and Rock, originally ran in the June 1953 issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.