PRESSED TIGHT to the starboard gunwale of his guide’s deep-V, anchored in the dirty roil of a rain-swollen river, retired cop Jeff Puckett powers through a racking lesson on leverage.

Calves straining, forearms burning, back aching, and with a purple bruise spreading low on his belly from the butt-end of a surf rod, Puckett applies more force to his side of the lever, but the object on the other end barely budges.

“It’s like dragging for a sunken car,” he grunts, grinning over the pain.

In mid snicker, Puckett’s dad, Gary, who has been sweeping his rod in wide arcs across the boat’s port side, suddenly sticks a fish of his own. Now the elder Puckett is learning all about leverage, too.

Father and son gradually winch their loads—two 40-pound paddlefish, each with a treble hook buried in its side—across the current, up to the surface, and back to the stern, where the guide hoists them aboard. Both fish are spawning females, bellies distended with shiny black eggs.

Those ova have come to symbolize both life and death for this species.

Each dark capsule contains genetic coding, DNA-borne traits that have allowed paddlefish to survive since the Mesozoic Era. In the slow chaos of time on Earth, flora and fauna come and go, emerge and then pass into oblivion. Yet this unique life form has been reproducing itself with few evolutionary changes for 75 million years.

But paddlefish roe also has another notable use—as an hors d’oeuvre served on toast points. And that’s where this fishing story gets messy.

Since the Pucketts are in Oklahoma, they’re not allowed to keep the full bounty of eggs from their catch. To remain within the law, Jeff and Gary are required to throw away most of the roe—or, alternatively, donate all of it to the state, which processes and sells paddlefish caviar worldwide, collecting some $2 million a year.

Officials say it’s all about fisheries research and salvaging a byproduct to generate supplemental funding for conservation.

Critics call it heavy-handed government. They worry about commercialization and market-driven poaching of a relatively fragile native species. And they question whether a fish-and-wildlife agency is exploiting a public-trust resource for a different kind of leverage, in which paddlefish are the lever and the object at the far end is profit.

Commercial exploitation of wildlife is what condemned many of America’s game species to decades of overharvest, these critics say, and gave rise to the establishment of state game agencies a century ago. Do we really want to go back to putting a dollar value on wild species?

GRAY GOLD

THE “CHEVROLET OF CAVIAR,” according to chef Wolfgang Puck, paddlefish eggs have been commercially available for more than a century, though traditionally they’ve been shunned by connoisseurs. Favor went to beluga sturgeon from the Caspian Sea. Their gleaming eggs, called pearls, are larger and firmer, with a sumptuous “pop” of flavor when pressed between the tongue and roof of the mouth.

But demand for the delicacy gradually outpaced supply. As beluga caviar grew scarcer, retail prices in the U.S. soared to $300 an ounce, fueling rampant overharvest, both legal and illegal.

“Throughout the world, the history of caviar is the history of fish population exploitation,” said Brad Schmitz, a Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Department fisheries manager, in a 2007 interview. “If caviar stocks are not tightly regulated, the fish population can eventually disappear.”

Exhibit A is the Caspian Sea’s beluga, where sturgeon numbers finally tipped into an actionable nosedive. International trade in wild beluga caviar was restricted in 1996 under the governance of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and banned entirely in the U.S. in 2005.

All of which caused aficionados worldwide to take a second look at the prehistoric, odd-looking fish from the Mississippi River basin.

CLASS OF ’99

SOME 450 RIVER MILES from the main stem of America’s big river, in the hilly uplift of the Ozarks in northeast Oklahoma, is Grand Lake. Nourished by two main tributaries, the 46,500-acre impoundment is the state’s most productive paddlefish fishery.

In 2004, technicians with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation (ODWC) were conducting routine netting surveys to assess fish populations in Grand when they discovered a significant change from previous years. Nets were suddenly laden with five-year-old paddlefish.

It was the first evidence that unprecedented spawning success had occurred in 1999. Biologists are unsure exactly what caused the huge spike in productivity, but they knew right away that a massive year-class of paddlefish was just two to three years away from reproductive age.

By 2006, forecasts showed, these fish would begin springtime spawning runs out of the lake and into the rivers. Commercial fishing had been outlawed since 1992, but the coming rush would be a boon to recreational snaggers who gather each spring to wait for the meaty, egg-swollen spoonbills to arrive. ODWC officials anticipated an extraordinary opportunity for research on paddlefish reproduction, recruitment, growth, and mortality.

And given the decline of beluga sturgeon, they anticipated making some money in the process.

DATA AND DOLLARS

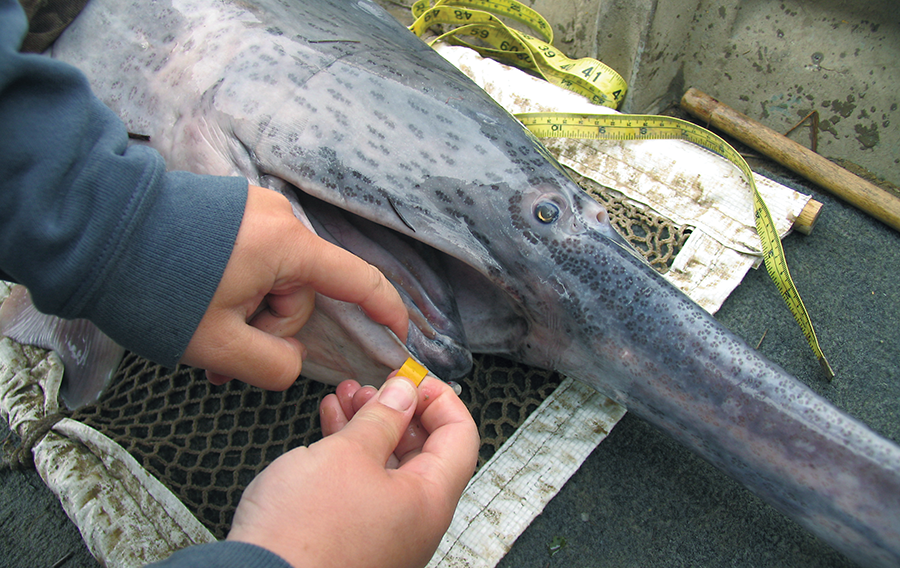

IN 2008, ODWC OPENED the Paddlefish Research Center above Grand Lake. Anglers are encouraged, but not required, to hand over both male and female paddlefish to the center. In return, fish are filleted, packaged, and returned to the angler for free, but the center keeps all of the roe. Some years, in the span of a few weeks, nearly 4,000 fish are donated.

Technicians collect data on each specimen’s sex, weight, length, age, and health. The massive data set has management value beyond the local fishery.

“ODWC’s research on population dynamics has been directly applicable to our work restoring paddlefish populations elsewhere in the region,” says Brent Bristow, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service project leader who works down state at the Tishomingo National Fish Hatchery. The hatchery uses broodstock from Grand to help reestablish paddlefish in other parts of its native range.

In addition to its research functions, the Paddlefish Research Center is a food-processing facility with sanitary protocols, inspections, and certifications.

Eggs can compose an astounding 25 percent of a female paddlefish’s live weight. Thus, a 40-pounder can yield 10 pounds of caviar, making it an extremely valuable prize—but only for ODWC. Regulations prohibit individuals from possessing more than 3 pounds of roe, and the private sale of eggs is strictly forbidden.

Once the roe is removed from the skein—the membrane that holds eggs together—it is screened, rinsed, salted, graded, and frozen in plastic containers, ready for sale.

Since this is a state enterprise, lots are sold in order to the highest bidder. On a continental scale, CITES lists paddlefish as “vulnerable,” a ranking between “near threatened” and “endangered.” But because the Grand Lake population is robust, and CITES recognizes that a resource’s monetary value is a motive for managing it sustainably, ODWC was granted permits to export caviar. The agency is now among the biggest wholesalers of roe in North America. Buyers come from around the globe, especially Asia.

The first year, ODWC sold more than 8,000 pounds. Production doubled in 2009, and reached a single-year high topping 18,000 pounds in 2013. All together, from 2008 to 2014, the agency has sold more than 97,000 pounds—48 tons—of paddlefish eggs.

ODWC’s total gross revenue from caviar sales exceeds $12.7 million over the past seven years. Proceeds go into the agency’s general fund, helping to pay for everything from paddlefish researcher salaries to game warden trucks to headquarters copy paper.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

SUCH FINANCIAL SUCCESS HAS led to conflict. Those fussing loudest over Oklahoma’s caviar operation are the outcompeted. Commercial outfits in neighboring states pay employees to harvest paddlefish. Now recreational anglers were paying ODWC, via fishing licenses, for the same job. Lower overhead, lower price.

“A government agency is depressing the market,” says Steve Kahrs, a caviar producer for Missouri’s Osage Catfisheries. “That’s our biggest issue with Oklahoma. They screwed everybody. We have interested buyers waiting for Oklahoma to set the price before they’ll buy from us.”

Another groan came from local snaggers. ODWC promoted the paddlefish bonanza and liberal creel limits, seeding an invasion of both resident and nonresident anglers. Oklahoma country music stars Blake Shelton and Miranda Lambert even joined agency leaders for a state-produced TV show about snagging paddlefish. The number of paddlefish anglers in Oklahoma tripled between 2008 and 2012.

The surge added to already-mounting pressures. Guides booked additional clients, boat traffic increased at a fishery once limited to bank fishermen, and new side-view sonar equipment allowed more anglers to locate and snag paddlefish staging in areas where no one had bothered to cast before.

Word spread among scofflaws, too. In 2014, paddlefish caviar retailed for about $25 an ounce. But buyers willing to deal in the black market could get it for half that price. Poachers took advantage of the fact that a 40-pound female paddlefish was worth $2,000. Game warden captain Jeff Brown told the Tulsa World newspaper that his team now spends “more time protecting paddlefish than any other critter.”

Oklahoma’s resident hunters and anglers haven’t seen a license fee increase since 2005, the longest interval since the 1960s. Nevertheless, for some sportsmen, the whole caviar saga leaves a sour taste.

“Maybe the state should take and sell a backstrap from every deer we kill,” lifelong Oklahoma hunter and angler Gary Giudice says mockingly. He adds, “There’s a market-hunting mentality surrounding paddlefish, and it feels wrong. We have great fishing and hunting, good habitat, and a diversity of wildlife. I know all that costs money. But it’s a shame that getting funding for conservation has come down to this.”

A WINDOW CLOSES

WHILE PADDLEFISH IN NORTHERN CLIMES can live 50 years, life is shorter at latitudes like that of Grand Lake. Here, survival after age 15 drops precipitously. ODWC’s paddlefish management plan predicts, “After 2015, the year class of 1999 will experience very high natural mortality as most fish that are not harvested will have lived out their natural life spans.”

The population spike was always destined to normalize—with or without additional harvest or research. Or caviar.

So how does a conservation agency balance a short-term opportunity for budgetary reward against its long-term duty to protect, manage, and sustain paddlefish for the citizens of Oklahoma?

It’s a question that clearly annoys ODWC fisheries chief Barry Bolton, who says the program’s only driver is science; the revenue side simply is what it is.

“The Paddlefish Research Center was built on the fact that anglers were going to harvest these fish anyway, and the fact that anglers aren’t allowed to keep the eggs. We’re salvaging roe that was going to end up as waste when these fish were cleaned,” says Bolton. “From the outset, our biologists, our agency, and our commission agreed to support this concept only if it was driven by research and doing what’s best for the resource. Since 2008, I’ve never seen a situation where that wasn’t the case.”

In 2008, anglers could keep three paddlefish a day. In 2010, the daily limit was reduced to one, with harvest allowed only on certain days of the week. In 2013, ODWC closed one of Grand’s main tributaries as a paddlefish refuge, and closed snagging at night. In 2014, the agency enacted a two-fish annual limit.

Bolton offers the progressively reduced limits—good for paddlefish populations but bad for the agency’s income—as proof that ODWC is resource first. He concedes, though, that every revenue stream is important.

“All conservation agencies today struggle with funding,” says Bolton. “Costs are going up, but hunting and fishing license sales are mostly flat or declining. Federal grants aren’t bridging the gap. To make up the difference, we have to be creative and rely on timber sales, hay grazing, ag leases, and oil and gas revenue.”

Caviar is one more commodity to help leverage the future of conservation.

DIY Caviar

The word “caviar” appeared in the English language in the 1500s, but Egyptians were pickling roe as early as 2400 B.C. In some cultures, caviar was reserved for royalty. In 19th century America, it was served free at saloons, where the salty flavor caused patrons to drink more beer.

Today, caviar comes from sturgeon, paddlefish, salmon, trout, and other species.

Chef Anthony Compagni of Benvenuti’s Ristorante in Norman, Okla., is well versed in the caviars of the world—and he’s partial to paddlefish.

“Beluga is the most famous, especially among caviar snobs. But for the American palate, paddlefish has a more enjoyable flavor, and it’s usually fresher,” says Compagni. “Paddlefish caviar can be served plain on a nice cracker, or with cream cheese, chopped green onion, Tabasco, or lime. Even people who don’t like caviar usually go nuts for paddlefish caviar served this way.”

For a delicacy of such fuss and fame, caviar is surprisingly simple to make.

Compagni recommends removing roe from the outer membrane, or skein, by sifting it through a pizza screen. Place the eggs in a colander and rinse with fresh, cold water. Then add sea salt totaling 3 percent of the weight of the eggs. It’s a classic process called malossol, Russian for “little salt.”