These almost unbelievable shark stories are from real captains who were lucky enough to walk away mostly unscathed. Their accounts are just a sampling of true events that have played out on the oceans lapping at our coastlines. We aren’t trying to scare you off the water. We just want to give you a bit of a heads-up for the next time you go offshore.

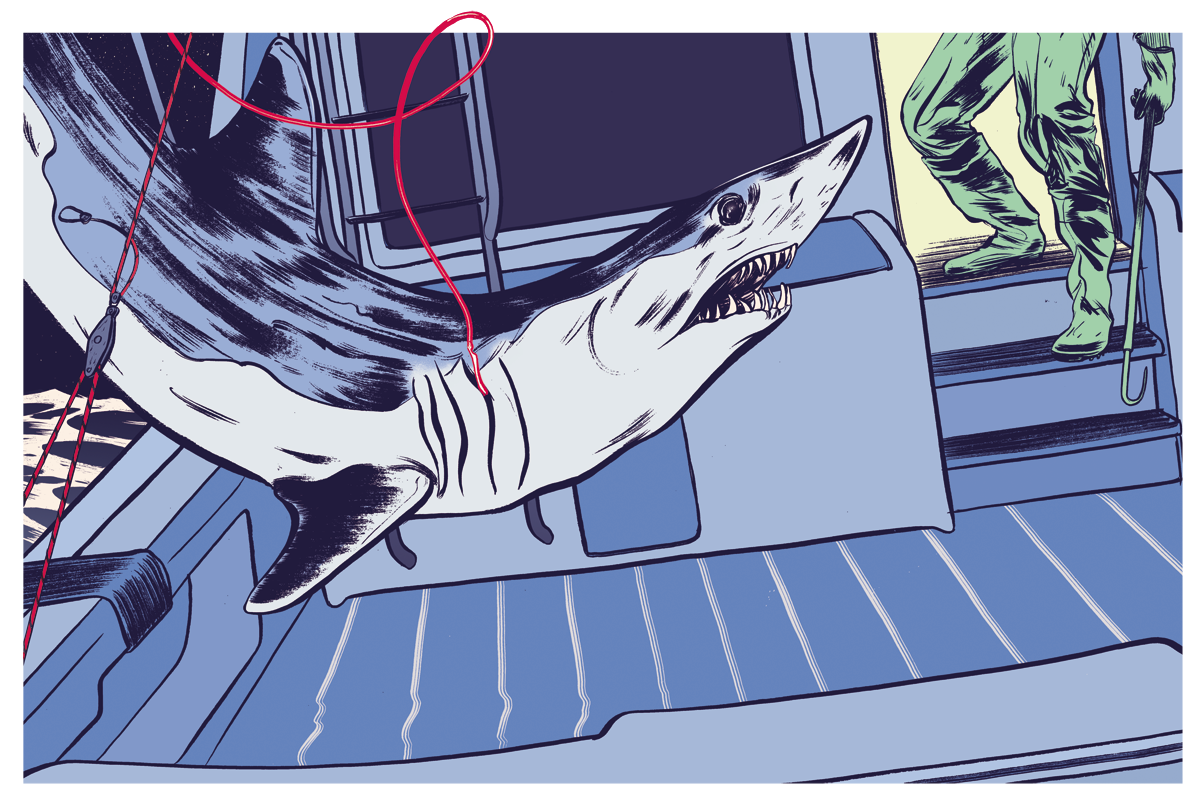

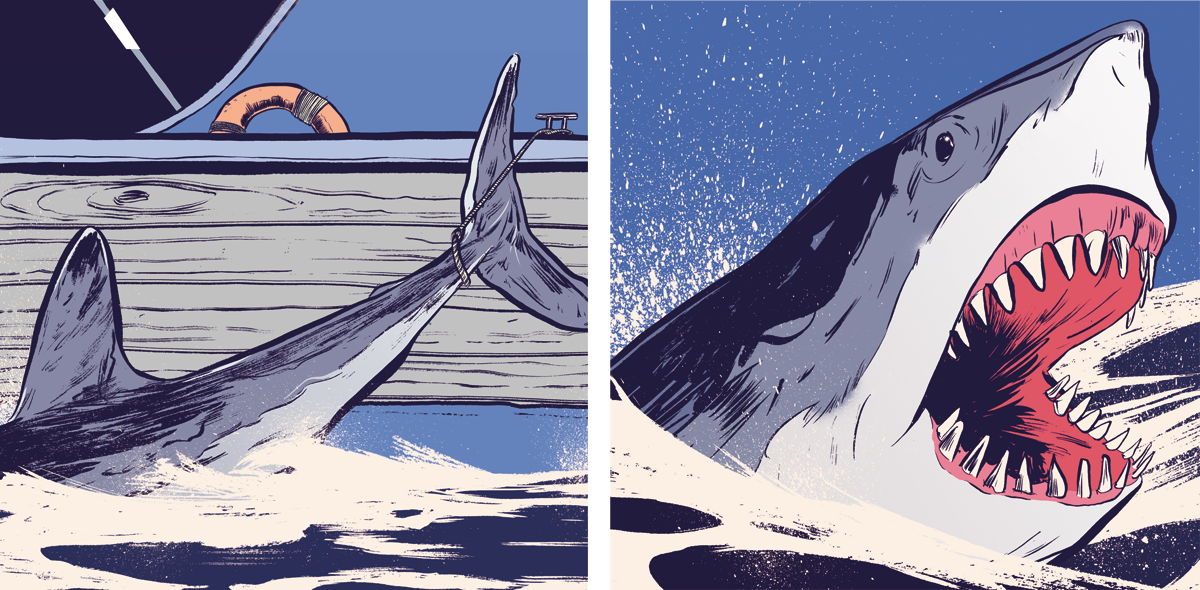

_** MAKO GONE WILD **_

The night was still and all the men were asleep save one. Devlin Roussel had drawn the short stick and had the midnight watch. He was the youngest angler aboard the Sportfisherman, and his grandfather, captain of the 52-footer, wasn’t about to forfeit sleep.

“We were tied to a buoy about 60 miles off the coast of Grand Isle, Louisiana. I was bored to death, so I figured I’d try and catch some tuna while the guys were sleeping,” says Roussel of that summer night in 1986.

“I started chumming with some trash fish we had caught. About 2 a.m., I heard something crash into the port outrigger, which was stowed up. I looked and saw a 200-pound mako shark coming down into the boat with the red outrigger halyard stuck in its gill,” Roussel says.

Evidently, the shark charged the chum slick and then free-jumped almost 6 feet into the air, colliding with the outrigger setup.

“Had that fish not hit the outrigger, it would have crashed directly into the cabin,” he says. “As it fell into the boat, the halyard broke, dropping the fish in the cockpit—fully alive.”

The 6 ½-foot-long shark went ballistic.

“We had recently replaced the fighting chair and the tackle station. So, of course, the first thing the shark bites is the fighting chair. It ripped that thing to shreds in a matter of seconds. Then it moved to the tackle station and, between biting the wood and pummeling it with its tail, turned it into a pile of splinters.”

By that time, Roussel’s grandfather and the rest of the crew were awake from the impact of the 200-plus-pound fish landing in the boat.

“My grandfather walked out with a pistol. At the sight of the shark and its trail of devastation, my grandfather aimed the gun at the fish. But he quickly reconsidered. We didn’t need a hole in the boat. Instead, we grabbed a couple of heavy-duty gaffs and eventually pinned the shark against the corner of the boat near the marlin door. As the shark latched on to one of the steel gaffs, bending it like a spoon, I grabbed a knife and started stabbing it. That didn’t go over too well,” says Roussel. The shark responded by releasing its hold on the gaff, doubling around and nearly catching Roussel’s ankle.

After wrestling with the creature for 20 minutes, the crew was finally able to open the marlin door and push the shark back into the ocean.

“It was the longest 20 minutes of my life. That mako ended our fishing trip. We had to head back to the boatyard the next morning. When all was said and done, that fish caused $15,000 worth of damage. The whole cockpit had to be rebuilt.”

_** FACE-TO-FACE **_

It was a gray morning off the coast of Point Judith, Rhode Island, on July 27, 1991, when Capt. Joe Pagano, his cousin Vinnie Cleri, and friend Steve Daniels spotted what appeared to be an overturned boat floating in the distance. The trio was only a couple of miles offshore and decided to investigate.

The boat turned out to be a 35-foot-long finback whale, freshly dead, leaking fluids for hundreds of yards. This slick had attracted an apex predator, its presence announced by 4-foot-wide chomp marks in the side of the carcass.

“We knew there was a big shark feeding on that whale,” says Pagano, “but we had no idea how big.”

The captain was marking the fish on his depth sounder when he saw an enormous hook on the screen. Something huge was near the bottom in 60 feet of water.

“We rigged up a rod with 180-pound mono and a doubled wire leader, grabbed the biggest tuna hook we had onboard, a 14/0, and drifted some baits by the carcass,” Pagano says.

No dice.

“Then we figured we should match the hatch, so we pulled up to the whale and Vinnie started cutting a chunk of meat off the carcass. All of a sudden, he stepped back breathless. Couldn’t say a word.”

While sawing off a piece of bait, Cleri had seen the shark—a great white of immense proportions. It surfaced just on the other side of the whale from where Cleri was precariously leaning over the side of the boat. He saw its coal black eyes. He saw its extended jaws full of serrated teeth wider than steak knives.

“He said this thing was bigger than we could handle. It really, really scared him. And he wouldn’t get next to the edge of the boat again,” says Pagano.

Eventually, they removed a 5-pound slab of blubber and attached it to the hook. (This was several years before using whale blubber for bait and intentionally fishing for great whites became illegal.) It took only five minutes for it to get bit.

“We let it run for almost a minute before we set the hook, which to this fish must have felt like a fly landing on your arm.”

The anglers expected the fish to freak out once they applied pressure, but it didn’t. The giant beast kept a slow and steady pace, almost indifferent to the annoyance of the anglers connected to it.

“We tightened the drag down as much as we dared, and basically reeled the boat to the shark,” Pagano explains.

Perhaps the most amazing part of this tale is that Pagano was not fishing from a huge vessel. His boat, the Osprey, was a simple 23-foot cuddy cabin cruiser. When the shark first surfaced, its length seemed to nearly equal that of the boat. The shark’s girth was nearly 10 feet.

After two and a half hours of being towed by the shark, the immense beast regurgitating enormous chunks of whale meat all the while, the three men had the great white boatside.

“We harpooned it, and it surged under the boat. Unfortunately, the harpoon line got caught in the prop. So, we harpooned it again and hand-lined it tight to the boat.” With Cleri holding his legs, Capt. Pagano was lowered head-first toward the water. His face was just inches from the surface, his elbows beneath the water untangling the mess, the huge shark idling within spitting distance.

Finally, the prop was freed and the three men tail-roped the shark. The battle was over. At the dock, the fish was measured and weighed by biologists: 15 feet 6 inches; 2,909 pounds. At the time, it might have been the largest fish ever caught by rod and reel.

_** AN INCH FROM DEATH **_

Capt. Steve Quinlan and his fishing partner were chumming off the Los Angeles coast when the monster shark first made its presence known. It was June 2006, the beginning of mako shark season, and the pair was chumming without a single baited line out, hoping to bring a beast up from the depths.

“When I target big mako sharks, I don’t want to fool with bycatch or small sharks. So, until I see a big fish moving into the chum slick, the baits stay in the boat,” Quinlan explains.

And by seeing a fish, he means seeing signs of an incoming giant. The seagulls tip him off.

“Seagulls land in the chum and pick off small pieces floating on the water. You can have an island of seagulls next to your boat if you chum long enough.”

After four hours of chumming, the raft of birds floating adjacent to his 29-foot Pro Line was significant—until the gull farthest back took flight. Then a couple more followed. And at once, a violent wave of flying, white, squawking gulls lifted and dispersed, completely leaving the area.

“When a big shark comes in, the seagulls get the hell out of Dodge,” says Quinlan. “They don’t want to become a meal.”

As the mako cruised toward the boat (they come in at 8 to 9 knots), it looked like a submarine about to surface, with water being pushed aside by the sheer girth of the fish. Then the tip of the dorsal fin broke the water. And all at once, the shark took form, just feet behind the boat. The pair of anglers immediately tossed out big hunks of tuna flesh to put the predator in a feeding mood.

“Once we saw her eat, we pitched our baits and she ate,” Quinlan says.

The fight was not abnormal for a fish of nearly 500 pounds and an estimated 9 ½ feet long. It took about an hour and a half for the pair to get the shark boatside. And that’s when everything went crazy.

“I had a flying gaff that had about 12 inches between the point and the barb, which means you really have to penetrate a fish to sink the barb in. Well, I hit her as hard as I could. The problem was, makos are very sensitive and flinch as soon as they feel that gaff point, so I didn’t sink it past the barb.”

When Quinlan went to push it in farther, the shark went nuts. Going from a horizontal position adjacent to the boat’s gunnel to perfectly vertical with one swipe of its tail, the mako flew out of the water toward the captain.

“Before I could react, I had a face full of shark teeth. I could smell her breath. I saw rancid meat between the rows of her jagged teeth. She snapped her jaws shut within an inch of my face,” Quinlan says.

He tried once more to secure the gaff, and the shark again attacked.

“The second time she came at us, she bit the side of the boat so hard it almost knocked us over. Her top teeth lodged in the rub rail, her bottom teeth penetrated not only the gel coat on the bottom of the boat, but also cracked the fiberglass!” the captain says.

With one final push, the barb found home and the shark was contained.

“Looking back, I was really lucky. Had I been bent over a little more, she would have had me. It was a humbling experience.”

Quinlan still guides for trophy makos, but he avoids potential gaffing mayhem by practicing catch-and-release.

_** THE QUOTABLE QUINT, FROM JAWS **_

“Here lies the body of Mary Lee; died at the age of a hundred and three.

For fifteen years she kept her virginity; not a bad record for this vicinity.”

“Front, bow. Back, stern. If ya don’t get it right, squirt,

I throw your ass out the little round window on the side.”

“I’m not talkin’ ‘bout pleasure boatin’ or day sailin’. I’m talkin’ ’bout workin’ for a livin’.

I’m talkin’ ’bout sharkin’!”

“Back home we got a taxidermy man.

He gonna have a heart attack when he see what I brung him.”