This story, Skull, Inc., originally ran in the June/July 2014 issue. You can find more stories from the last 15 years of Outdoor Life here.

LIKE PAINTERS AND SCULPTORS, taxidermists develop their own artistic style and signature. Capes are their canvases and Styrofoam their clay, their medium for expression. But skull mounts are different. There’s no room for creative license or interpretation. Just the irreproachable beauty of bone shaped solely by the hand of God, or, if you prefer, by the forces of evolution.

Or maybe we, as hunters, love skulls simply because they look so darn cool.

However deep or superficial your attraction to wildlife osteology, you’re probably among the congregation of America’s foremost temple of skull and bone: Skulls Unlimited International.

Though few natural-history buffs realize it, many of them have admired the handiwork of this unusual company, located in the ragged outskirts of Oklahoma City, for decades. Skulls Unlimited is the world’s leading supplier of museum-quality skulls and skeletal specimens. Its products are everywhere, from local nature centers to the Smithsonian Institution, and from junior-high science classrooms to the labs at Harvard Medical School. And more and more, its craft is gracing the dens of hunters.

“We’re now cleaning and whitening more than 50,000 skulls per year, and one of our fastest-growing services is processing big-game skulls,” says Jay Villemarette, who founded Skulls Unlimited in 1986. “In 2013, we did more than 2,000 whitetails alone.” That’s at $125 a pop.*

Bare Bones Beginning

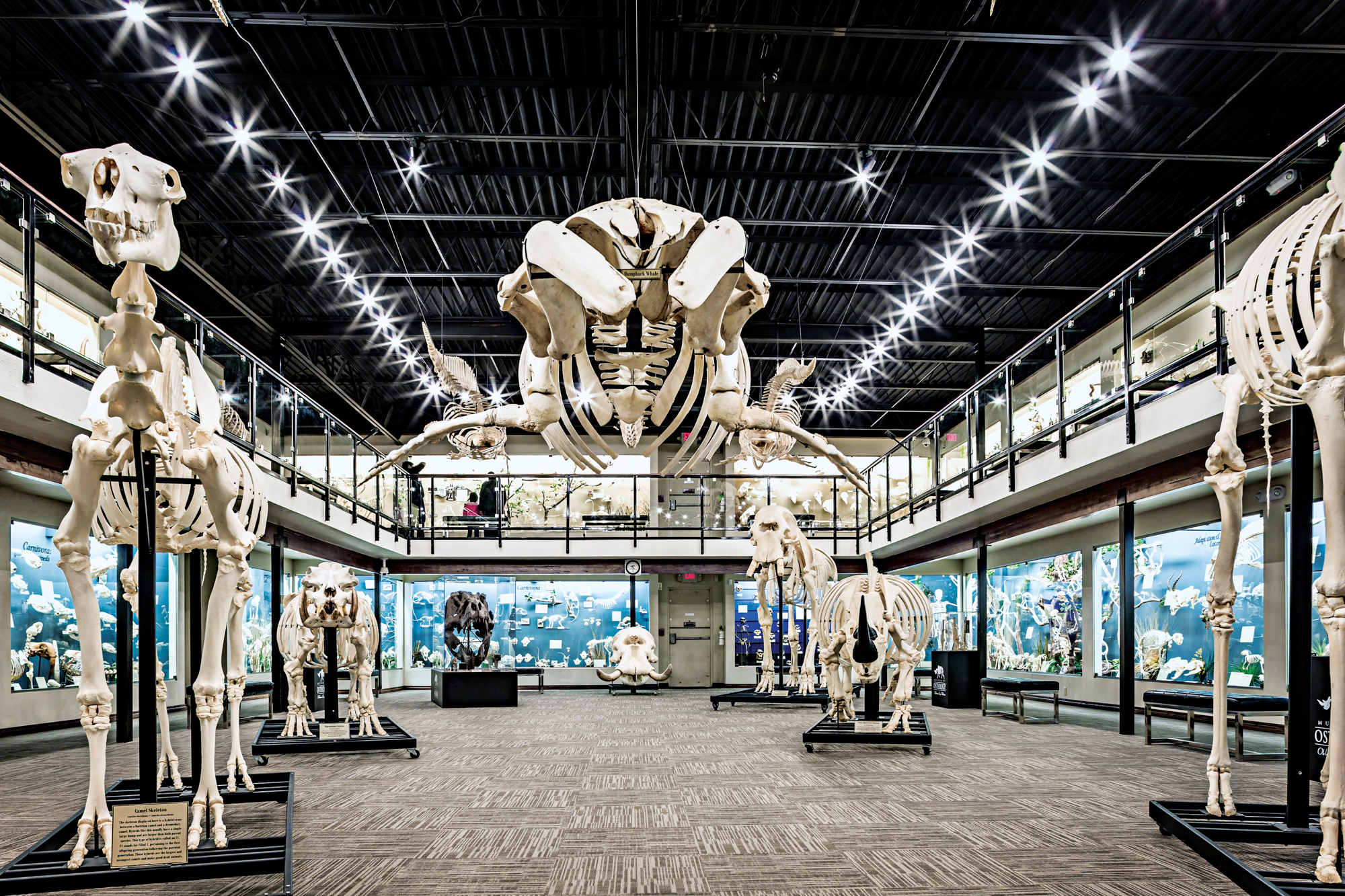

In the early years, Villemarette and his wife operated the business out of their kitchen. Today, the company has 21 employees and a campus with two buildings in a light-industrial area southeast of downtown. The main building houses an impressive 7,000-square-foot Museum of Osteology and a gift shop. On display are some 300 full skeletons and 400 skulls. It’s professional and orderly, but some visitors literally become faint or nauseated. Nevertheless, the museum is a growing attraction and can be rented for weddings, birthdays, and other private events.

An adjoining shipping area is a pulse of commerce. What began 28 years ago with a one-page price list is now a retail and mail-order firm with a 130-page catalog and online sales worldwide. Christmas is the busiest time. Need a stocking stuffer for your kid? See page 8 to order a shrew for $29, plus shipping and handling. A staffer will pluck one from a bin of shrew skulls and send it express. How about a bison? Page 75: $349 large, $260 average. In between those physical extremes are skulls, claws, eggs, and other artifacts from hundreds of species, game and non-game, common and endangered–even extinct–from around the planet. Some are replicas; many are real.

Villemarette is sensitive to perceptions that he is over-commercializing wildlife. A letter on the catalog’s first page assures customers that Skulls Unlimited resells specimens attained only through legal and ethical means, such as roadkills, natural deaths, and zoo attritions, and from regulated hunting and trapping.

Skulls also are acquired under unusual circumstances. In early 2014, the company purchased and began advertising an assortment of California sea lion skulls. The Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 generally prohibits possession of sea lions, but this was a research collection dating back to the 1950s, exempt from the act’s protections. Each skull comes with a bill of sale and letter of authorization from the federal government.

Another area of sensitivity is human remains. Villemarette is careful to respect the dignity of those who’ve donated their bodies to science. His company discreetly receives, cleans, whitens, and markets human skulls and skeletons for sale strictly to medical, educational, and academic institutions. Human skulls are graded and priced from $1,250 to $1,850, based on bone quality and number of teeth.

Villemarette says the laws governing ownership of animal parts are actually more restrictive and complex than those for human parts. Why salvage the mortal remains of humans? They are an invaluable tool for medical research.

“If you break your arm,” Villemarette says, “would you rather see a doctor who has experience with real human bone, or replicas made out of resin?”

Repository of Death

From the relatively sterile front building, it’s a few steps across a parking area to Skulls Unlimited’s second building. This is where raw materials arrive for processing. Local UPS and FedEx drivers learn to find the receiving door quickly, eager to offload the boxes with the highest odds of becoming the day’s smelliest delivery. Insurance regulations prohibit public entry, citing “mental anguish” concerns for visitors. The TV series Dirty Jobs filmed a stint here, with host Mike Rowe visibly aghast.

As the door opens, you catch your first whiff of putrefied meat and bleach.

Behind the door is mostly what you’d expect: fuming stench, workers with knives, glass tanks filled with flesh-eating beetles, plastic tubs for various chemical baths. But on autumn days, the volume and variety of critters is amazing. Amid the piles of deer is all manner of fauna. Wildebeest, elk, lions, pronghorns, snapping turtles, baboons, wolves, and warthogs wait, oozing, for their turn in the lineup.

The room seems to assault all five senses, yet Villemarette suddenly raises his nose to a comparatively delicate and unexpected scent.

“Salmon!” he announces, explaining that the beetles sometimes emit the odor of whatever the animal had been eating. Sure enough, one of the aquariums held a half-cleaned Alaskan brown bear skull.

Piecing It All Together

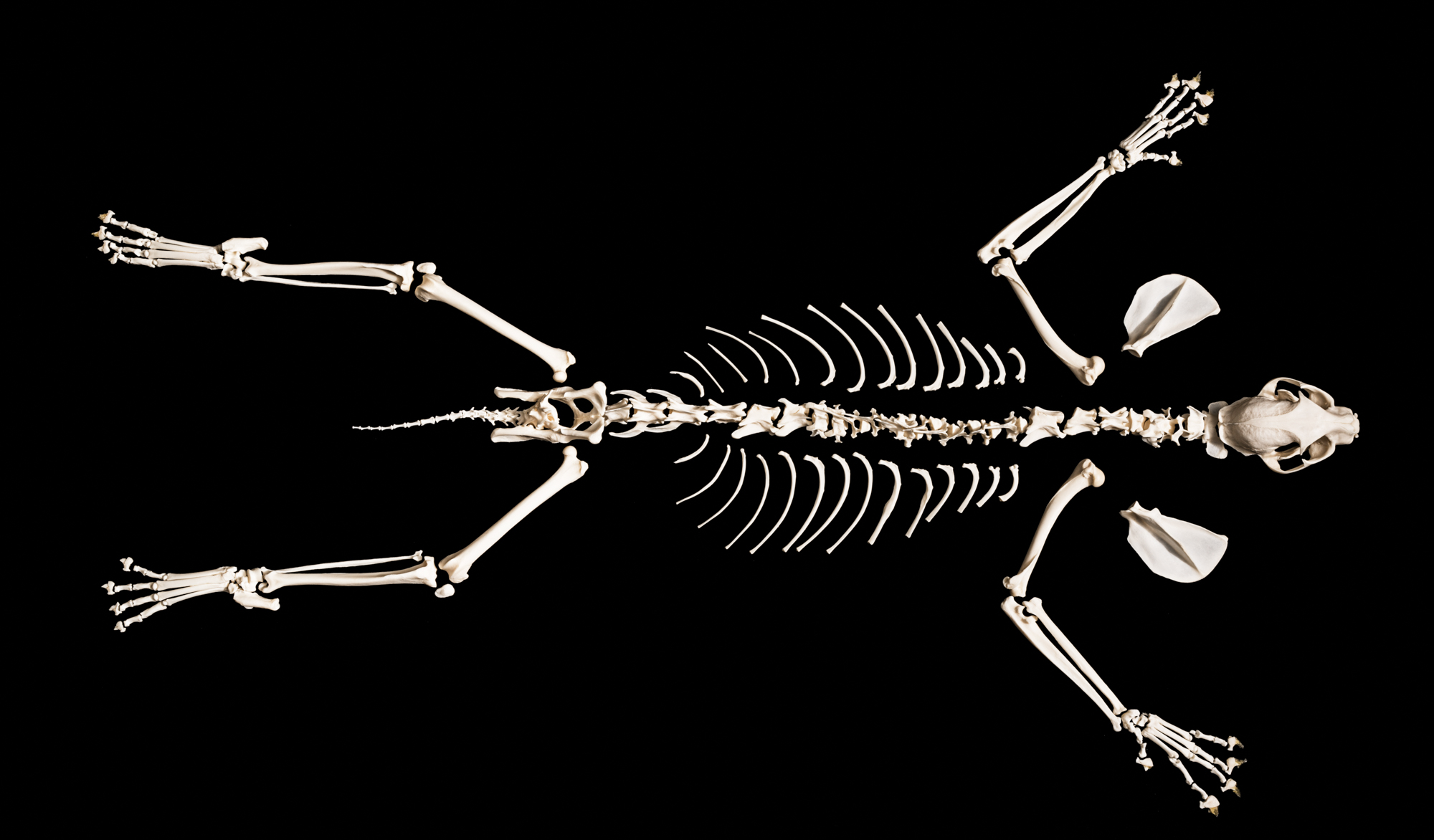

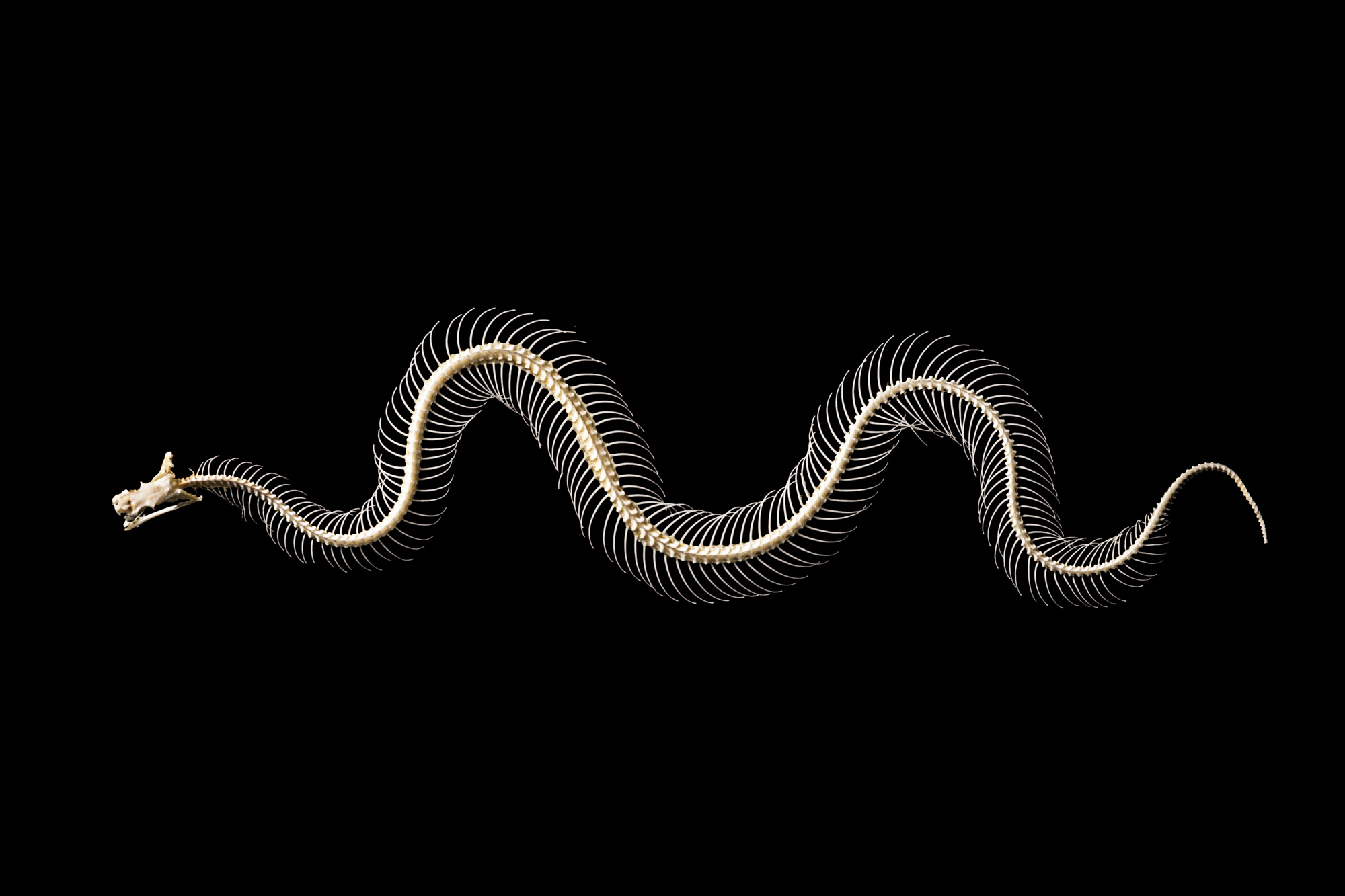

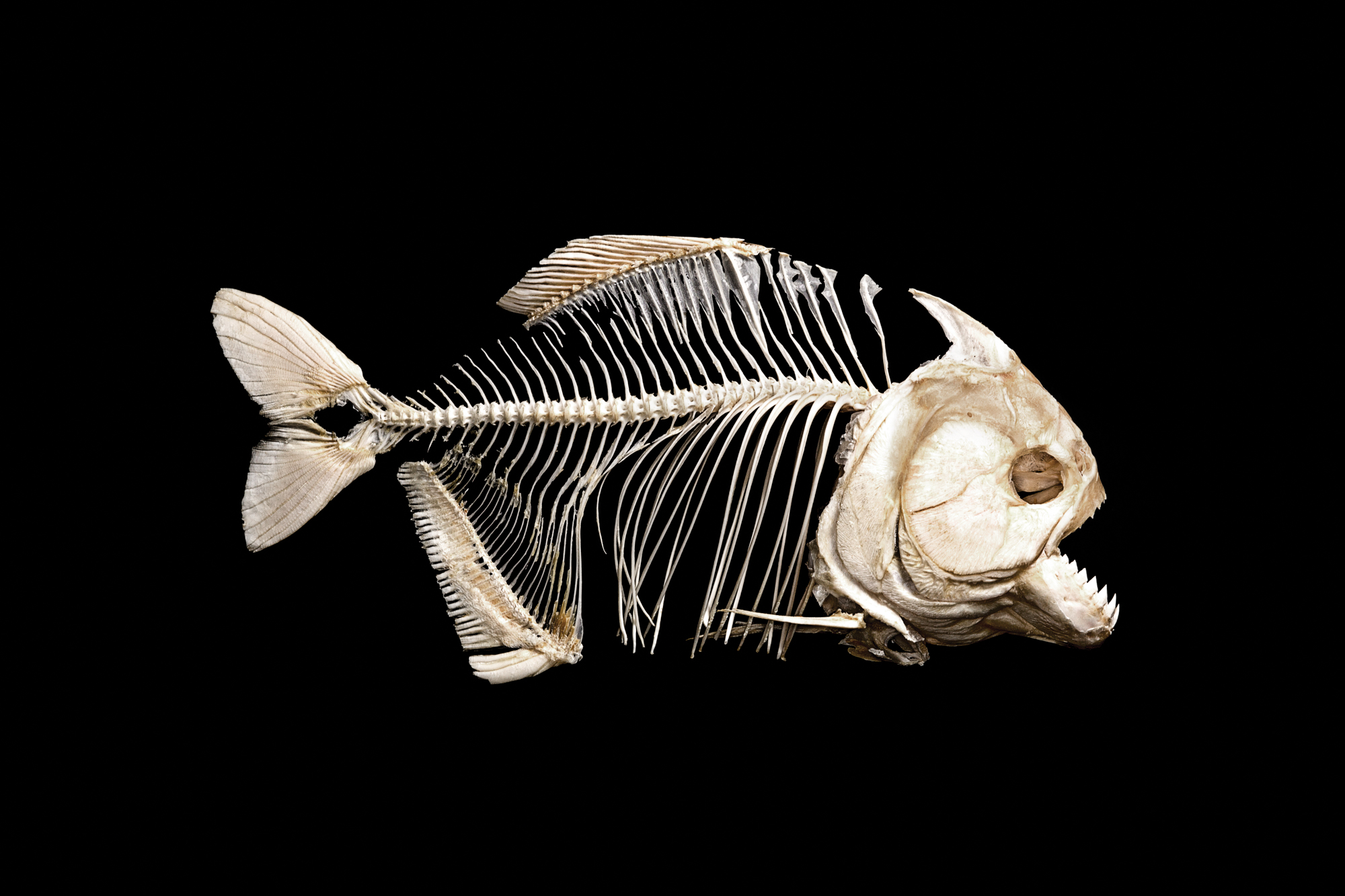

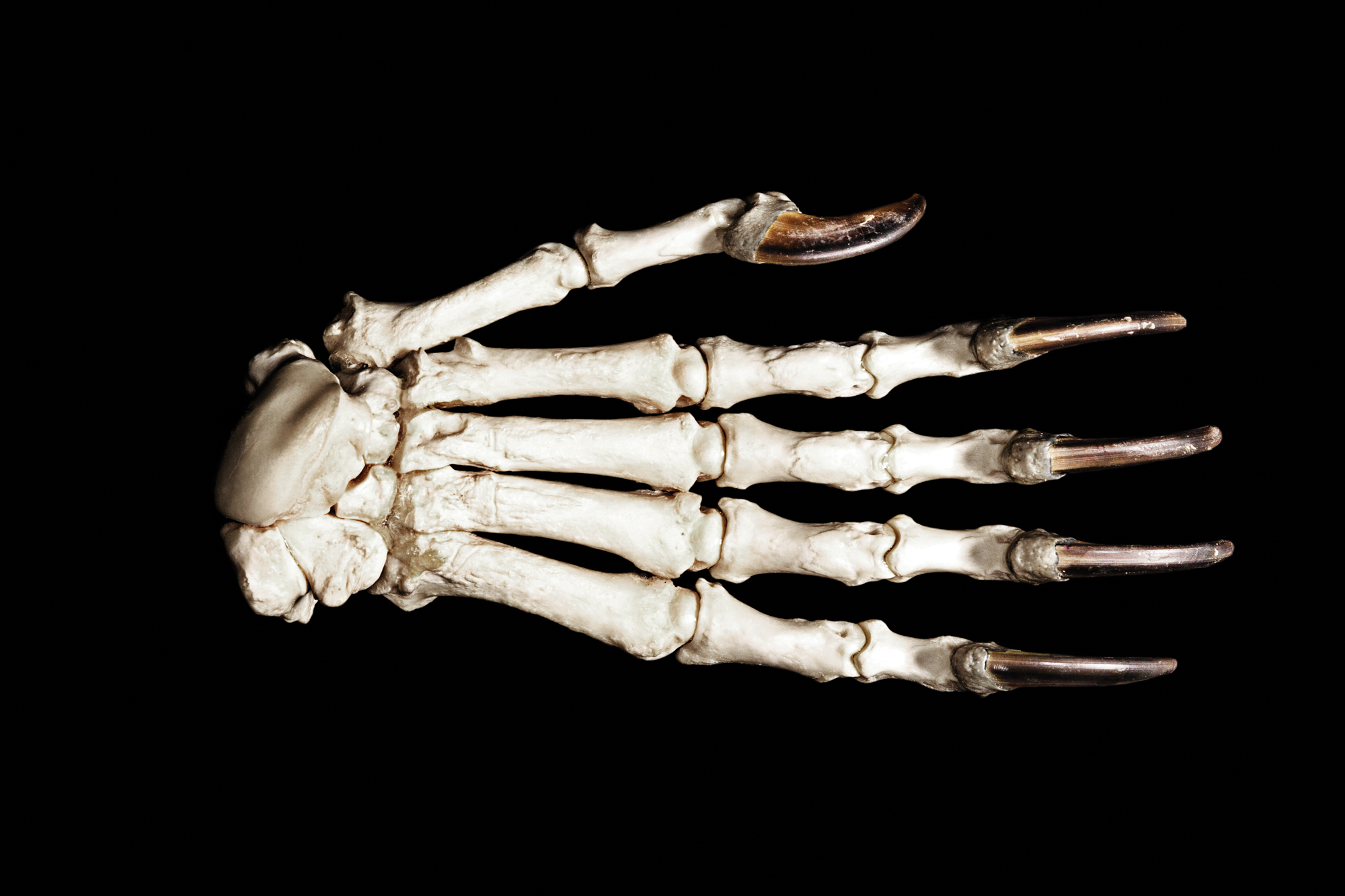

Ironically, the most artful aspect of the business occurs in a room adjoining the carnage, where newly cleaned, dry, white osteological specimens are staged. Along with custom-processed game skulls and various animal skulls for general sale, there are fishnet bags of loose bones ready for assembling into complete skeletons. Articulation is another growth area for Skulls Unlimited, and it requires employees with specialized skills. With their studied knowledge of anatomy, kinesiology, and composition, and trade skills ranging from carpentry to welding, articulators are equal parts Leonardo da Vinci and Tim the Tool Man.

As a demo, one of the artisans dumps a sack of more than 200 bones (a gray fox, incidentally) into a random jumble on a workbench. Instinctively, he begins sorting and laying out parts. Vertebrae are quickly aligned behind the skull and extended through the end of the tail. Ribs are positioned in order on either side. Limbs are quickly assembled from shoulders and hips down to the phalanges.

Articulators fasten bones together using drills, wires, rods, and glues. An epoxy compound is concocted to replace discs between vertebrae and other cartilaginous elements, so the animal returns to its original dimensions and structure.

The shop is filled with skeletons locked in dramatic poses. A coyote runs flat-out. A leopard attacks a springbok. A whitetail buck turns to check its backtrail.

“Most skeletons are for educational institutions, but we also do a number of dogs and cats for people who want to memorialize their pets,” says Villemarette. “And we’re hearing from more hunters who are now considering articulated skeletons instead of full-body mounts.”

Dog and cat skeletons start at $995. A quail hunter who wants to keep ol’ Banjo in his stylish high-head-and-tail-pointing stance will spend closer to $1,800. Complete whitetails run $5,400.

Despite upward trends, realistically, bare bones aren’t destined to replace classic taxidermy as preferred trophy-room decor. Lifelike mounts will always be more popular for preserving special experiences afield, because an animal’s visible beauty and character are showcased by skin, not skeleton. Still, within many hunters and anglers lives an avid naturalist who is nearly as fascinated by the functional beauty that lies beneath fur and feather.

We’re attracted to skull mounts not so much because they’re comparatively cheap, but because they rouse our curiosity and we marvel at the physiological adaptations that make every game species what it is–a masterpiece of its environment.

And because they look so darn cool.

How to Sell Your Skulls

If you already sell squirrel tails to Mepps for use in their inline spinners, listen up: There’s a valuable by-product at the other end of the carcass, too. Skulls Unlimited buys hundreds of skulls and full skeletons–of squirrels and other species–every year. The company is always on the lookout for both unusual and common specimens.

The process is simple. Email a photo of the item along with your asking price. If there’s a deal, and all is legal, you’ll ship the item to them and receive payment

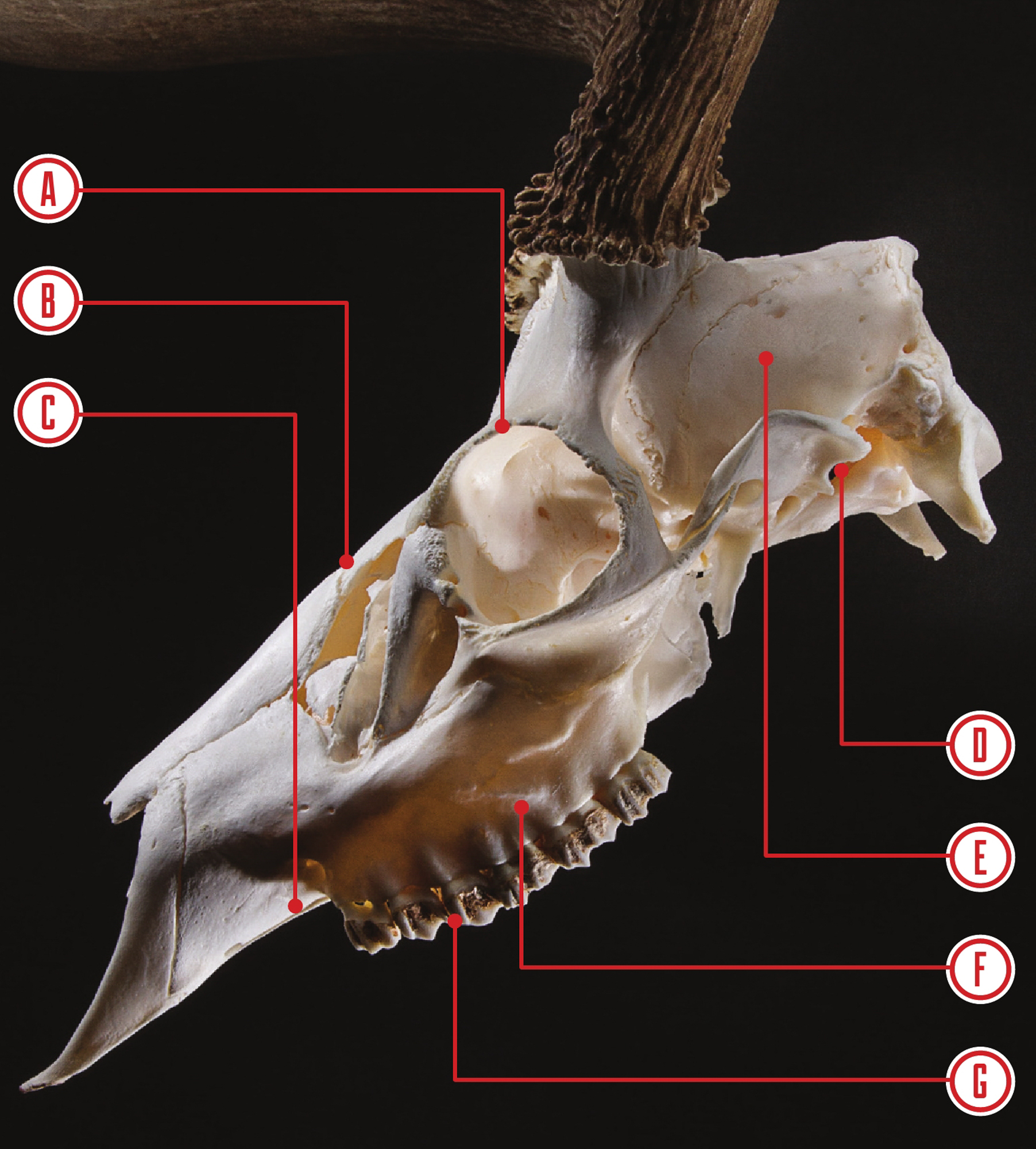

Anatomy of a Deer Skull

A) ORBIT: Eye sockets on the sides of the head are a classic feature of prey species, providing wide-view defense against predators. Deer can spot movement in a near-310-degree field of view.

B) ROSTRUM: This bony structure protects the large, elongated nasal canal filled with membranes that capture scent particles. Research suggests a deer’s nose is 100 times more sensitive than a human’s.

C) HARD PALATE: Like other ruminants, deer have no upper front teeth. A hard palate provides a broad bite surface for the lower incisors, an adaptation that allows faster feeding and less time exposed to predators. Deer can eat by quickly tearing and pinching off vegetation, then returning to cover to regurgitate and chew cud.

D) AUDITORY BULLAE: Sound collected by a deer’s large, swiveling outer ears is funneled through small, conical ducts into these bulbous structures protecting the middle and inner ears. Deer hear better than humans, but not nearly as well as predators like cougars, which have large, highly developed auditory bullae.

E) CRANIUM: A hard case for the brain, the center of the nervous system.

F) DIASTEMA: The large gap between the hard palate and cheek teeth acts as a pocket for holding food items while browsing, and for manipulating cud.

G) PRE-MOLARS AND MOLARS: These are designed for grinding tough plant material.

A biologist in 1949 was the first to estimate deer age by examining wear and eruption patterns of cheek teeth in the lower jaw. Correlations between age and upper teeth are relatively unstudied.

*This story was published in 2014. Current skull cleaning prices are $169 for a whitetail.

Read more OL+ stories.