It happens every year. The leaves change hues before finally tumbling to the ground. Science explains why.

About the time the leaves begin to fall, the Great Lakes salmon run is in full swing as adult cohos and chinooks return to the very same gravel runs where they were hatched. Science explains why.

And just as the final few salmon are fulfilling their biological duties, the whitetail rut is starting to crank up. And science explains why.

Trouble is, as deer hunters, we haven’t always based our understanding of the whitetail rut on science so much as on assumptions. But thanks to the work of researchers and technology, we now know these nine truths about the rut, which offer a glimpse into what bucks might be thinking during deer hunting’s best time of year.

1. Rut Range: There’s No Place Like Home

What Science Says

It would seem that bucks—especially older ones—have a thing for Dorothy’s mantra.

“For a long time, hunters really believed that bucks were running wild during the rut and that they pretty much abandoned their home range to find does,” says Kip Adams, director of education and outreach for the Quality Deer Management Association (QDMA). “We now know that’s just

not true.”

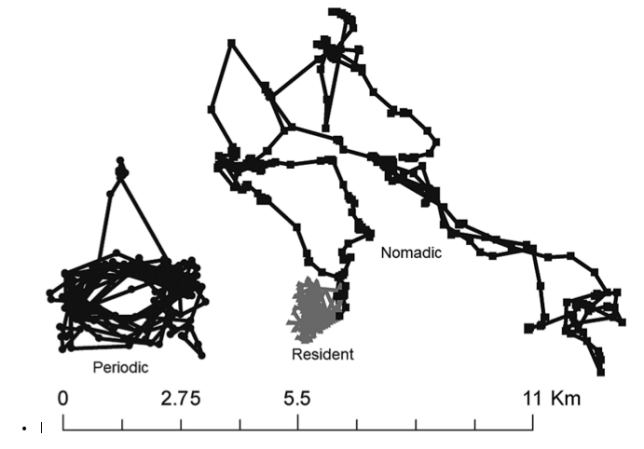

A study published in 2012, conducted by researchers Aaron Foley, Randy DeYoung, David Hewitt, Karl Miller, Ken Gee, and Mitch Lockwood, analyzed data from GPS tracking collars on 106 adult whitetail bucks in South Texas during a four-year span. The radio collars recorded the locations of those bucks every 15 to 20 minutes throughout the fall and winter.

The results showed that bucks utilized just 30 percent of their home territory (almost 3,000 acres on average) and, in fact, remained in just a few focal areas ranging from 60 to 140 acres in size within those areas.

What You Should Do

“Bucks may go on excursions outside of their home range,” says Adams. “But most of the time, they’re going to come right back home. As a hunter, that’s what I need to know. If I can pin down the core area of a buck, the odds are pretty good that he’s going to be spending some time there during the rut.”

Dr. Grant Woods, one of the nation’s most respected whitetail biologists, added that this research also indicates that bucks aren’t going to leave an area simply because does are no longer present.

“The commonly held myth—that if you kill does prior to the rut, the bucks are going to leave and go looking for them—is simply not true, and the research proves it,” he says. “Safety trumps all. Bucks, especially older ones, want to feel safe. A buck doesn’t have the capacity to reason that there might be some more does over the next ridge.”

2. Lunar Phase: Don’t Blame It on the Moon

What Science Says

Had Carl Sagan been an outdoors writer, he’d likely write about the moon and its impact on the rut. After all, there has to be some sort of correlation, right? Not so much.

“There is very clear, very accepted scientific data regarding the impact of moon phase on the timing of the rut,” says Woods. “I was part of a group of 14 scientists collecting conception dates from does. We backdated the date of conception based on date of birth. It was a very large sample size, thousands of deer from several different regions.

“And we found zero correlation to moon phase and the rut’s timing. None.”

More recently, the moon-rut question has been addressed in a study published in the March 2012 Wildlife Society Bulletin by a team from Mississippi State University. That study utilized fawning information from MSU’s Donnie E. Harmel research facility (data from 1976–1996) and the Kerr Wildlife Management Area in Texas (data from 1976–2003). The team also used deer population-level data from the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks for 10 different herds sampled from 1991–2004.

The results? Moon phase had no impact on conception date, thus no impact on the timing

of the rut.

What You Should Do

Although there is zero evidence to support the notion that the moon phase triggers the rut, the question of whether it impacts the rut at all remains. A North Carolina State University study, presented by researcher Marcus Lashley at the 2014 Southeast Deer Management Study Group, indicates that it does—somewhat. Full moons, for example, caused a spike in midday deer movement. The new moon caused movement peaks near dawn, and non-quarter moon phases caused an escalation in midmorning movement—great clues as to when to put in the most

stand time.

3. Storm Fronts: Weather or Not

What Science Says

There are few things more reviled by deer hunters than a warm front in November. Why? Because many feel that it will “shut down the rut.”

Well, actually, it won’t.

“Deer are going to breed when they are biologically conditioned to breed. The weather will not stop that,” says Adams. “The science on this is very clear. The same studies that illustrate that moon phase has nothing to do with the timing of the rut also serve to provide solid evidence that the rut is not triggered by a cold snap—or any other weather-related factor.

“The conception dates were very consistent from year to year,” says Woods. “Sure, there would be some very small variations—a matter of a day or two. But by and large, those conception dates were very similar. And remember, this data was collected from many different areas over several years. There were variations from year to year in temperature and weather conditions, and yet the conception dates remained stable.”

In the Mississippi study, which focused on conception-date variation, the wild, free-ranging whitetails in the study had a standard variation of the annual mean conception dates of just four days in mid-November, meaning those does were usually bred within the same four-day period each year, which is an indication that photoperiodism rules the rut.

What You Should Do

“Once bucks lose their velvet, they tend to move mostly after dark, and the peak times of movement—even during the rut—are going to be those crepuscular times, first and last light,” says Adams.

“A warm spell can influence the rut in that regard but not breeding. The deer are still going to breed when the time is right, but they’re likely going to do it during the coolest parts of the day, and that’s likely going to be after dark.”

Research published in 2012 from a seven-year study of 17 does and 15 bucks, conducted by researchers from Mississippi State University, Texas A&M University, and the Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, found that weather does have somewhat of an impact on movement patterns, but a very small one, with temperature being the most influential factor.

4. Lockdown Phase: Why Deer Disappear

What Science Says

It’s arguably the most dreaded period of deer season outside of the infamous October lull: lockdown. It’s that period of time when bucks are lying low with does and peak breeding is under way. Suddenly, it seems, there are no bucks to be seen.

University of Georgia researcher Andy Olson is working on a much-anticipated thesis that indicates the lockdown isn’t what we perceive it to be.

Olson’s research involved following three mature bucks in Pennsylvania throughout the 2012 rut—through October, November, and December. Using waypoints relayed from a GPS collar every 15 minutes, Olson was able to plot specific movements and patterns of those bucks.

And they never stayed in one spot very long.

What You Should Do

How can it be that Olson’s research indicates that bucks don’t shack up with does for several days at a time when we’ve each likely witnessed the lockdown firsthand?

Perhaps it’s because we’re looking at things in the wrong manner. Olson’s radio-collared bucks were with receptive does for fairly short periods of time—24 to 48 hours. And then they were frantically on the move looking for other hot does. During that time, they covered a lot of ground and spent time in defined areas within their home range.

As hunters, we’re usually posted up in one area. Same with our trail cameras. Bucks that are covering ground aren’t likely to pass by the same trail camera too many times. And if we focus most of our hunting efforts solely on one key area of a buck’s range, the odds are high that we simply aren’t there to see when the bucks are up and actively seeking estrous does.

5. Rut Sign: What Rubs and Scrapes Really Mean to Deer

What Science Says

It’s a classic rut-related tactic: Find a rub or scrape line and post up nearby, waiting for the buck that created it to cruise by while checking its territory.

The reality?

“That’s not going to happen, because bucks aren’t territorial. They aren’t marking any territory with rubs and scrapes. If they were, they’d make a rub and then stand by it and guard it,” Adams says. “What they’re doing is actually the exact opposite: Those are communal locations. They’re inviting other deer to check out that area by leaving scent and visual indicators. They don’t want to keep other deer away from the location—they’re inviting them in.”

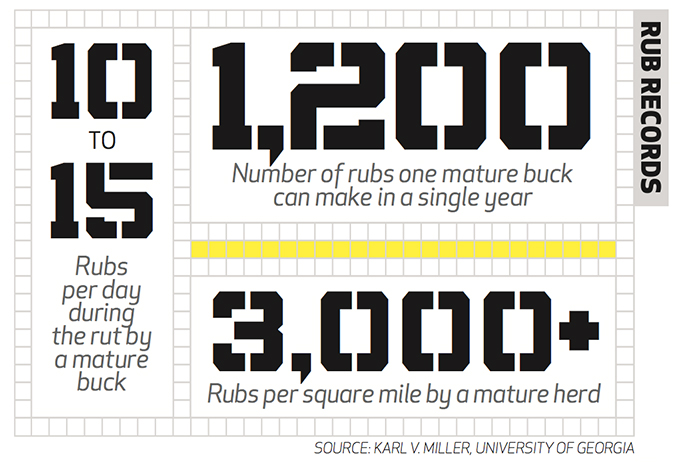

Perhaps the most groundbreaking study that led to this understanding of the role of rubs and, particularly, scrapes was presented at the Southeast Deer Study Group in 1998, when a University of Georgia research team revealed findings proving that many different bucks, including sub-dominant animals, will use and create scrapes.

Another University of Georgia study, this one from 2000, adds even more intrigue with findings that showed that does—not bucks—were the most frequent visitors to scrapes.

What You Should Do

“Coyotes and wolves defend their territories,” Grant Woods says. “Whitetails do not. Hunting near rubs and scrapes during the rut is an extremely popular tactic for a lot of hunters, but it’s probably not a terribly effective one.”

So what’s your best move?

“Those scrapes are likely going to be visited more frequently when the rut is just starting to take off,” says Adams. “But most of those visits are going to occur after dark. So if I’m going to hunt a rub line or a scrape, I’m going to hunt the travel routes to and from them in the hope of catching those deer in the daylight.”

6. Rut Intensity: The Truth About Busted-Up Bucks

What Science Says

Here’s another classic “heard ’round the deer-hunting world” line of November: “I’m not even seeing any does right now. They’re all worn out from the rut and are laying up somewhere.” But here’s the truth: Those tired does are living the good life, according to a study in South Dakota, funded by the QDMA, that looked at the impact of the rut on whitetails.

“The costs of reproduction are much higher for bucks than for does,” says Grant Woods. “Bucks are going to lose about 30 percent of their body weight. Now that’s a number people have probably heard before, but think about it for a minute: A 200-pound buck is going to weigh about 140 pounds at the end of the rut.”

“It was pretty amazing just how little those bucks are eating,” says Adams. “They’re burning a ton of calories by moving, chasing, and breeding, and they aren’t replacing them.”

What You Should Do

When it comes to hunting tactics, Adams and Woods have different tacks for taking advantage of this scientific fact.

“More and more, I’m hunting thick areas and focusing less on food,” Woods says. “That’s where those bucks are—in the thick stuff looking for does and sticking with the ones that they do find.”

Adams, on the other hand, thinks food sources can still play a key role. “The bucks—especially when does are first starting to come into estrus—are going to be in areas where the does are,” he says. “That’s why you’ll still find bucks near those food sources. Not because they’re feeding, but because that’s where the majority of the does are.”

7. Peak Periods: You’re Hunting the Worst Part of the Rut

What Science Says

When a doe is ready to breed, she doesn’t travel much during that 24- to 48-hour period. But she knows just where to go—thick cover. Does are tough to find. So, are there alternatives?

“Those old does are pretty smart,” says Woods. “They’re not going to hang out in the open and get chased around a bunch. They’ve learned to avoid that. They like to get back into thicker areas where they’re harder to get at.”

But what about yearling does that are cycling for the first time?

“That’s my favorite time to hunt the rut. It’s the best time,” Woods says. “Those doe fawns, when they reach about 70 pounds and are ready to breed for the first time (usually in December in the Midwest), aren’t very smart. They’re going to continue to follow the patterns of other deer.”

What You Should Do

To take advantage of this, Woods places plenty of focus on second-rut activity in December, when those doe fawns are starting to cycle but don’t quite have a firm handle on what’s going on. It may not be as intense as the primary rut, but deer are more patternable.

“They will hit the food in the evenings with the other deer, and those big, old bucks will generally follow right along with them,” Woods says.

“During the rut in November, it’s so hard to predict where deer will be. That’s not the case during the secondary rut. For me, that’s the very best time to hunt the rut.”

8. Breeder Bucks: Stud Bucks Don’t Exist

What Science Says

You’ve likely heard plenty of coffee shop chatter about the dominant “breeder buck.” Well, here’s some information you can stir into the conversation: “There’s no such thing,” says Woods. “In areas where the buck-doe ratio is somewhat balanced, there is no such thing as an old stud that’s breeding all of the does.”

Think about it for a moment and Woods’ statement—and the research behind it—makes

plenty of sense.

The rut, despite traditional thinking, is not a long, drawn-out affair. It actually takes place over a fairly short window of time (a week or so), during which the majority of does are bred. Each buck will spend somewhere around 24 to 48 hours with a doe that is receptive to breeding. And then the buck is on to the next one.

But while that “stud” buck is breeding that doe, other does are coming into estrus as well. And they’re being bred by other bucks.

In fact, in many instances, the same doe is bred by multiple bucks. This has been proven in several studies, including the first ever done on the subject in 2002 by Anna Bess Sorin from the University of Michigan.

What You Should Do

If you’re selectively harvesting bucks with the hope of affecting the genetic makeup of an entire free-ranging herd, you might want to reassess your strategy. Rather than holding out for the proverbial stud buck, a better tactic would be to set your sights on a mature animal. “Position yourself where the does are for the best odds of seeing a dominant buck,” says Adams. “There will certainly be other mature animals sniffing around.”

9. Scent Know-How: Deer Pee Is Not Magic

What Science Says

If you want an easy way to know when the rut is starting to crank up in your hunting area, just check the shelves of your local sporting goods store for empty racks that were once filled with bottles of doe-in-heat lure. But does it really work? The science says probably not.

“I’ve seen live, captive does that I knew were ready to breed because we saw them stand for bucks. We’ve extracted urine directly from that doe and placed it in areas with other bucks, and the bucks showed absolutely no reaction to it,” Woods says.

But Woods was also quick to note that bucks in the area of those hot does were very interested.

“Clearly, there is something there that we don’t really understand,” he says. “Maybe it’s a chemical reaction that occurs with the urine and the skin of the deer. But whatever it is, we’ve not been able to bottle it because it seems to break down very quickly.”

What You Should Do

“There’s some evidence that bottled scents have a level of effectiveness,” Woods says. “So many guys have used it and had dramatic results. Why? I really don’t know. But that’s hard to ignore.”

His best advice is to not be afraid to try urine-based scents during the rut. But don’t be too disappointed if they fail to bring bucks running.