We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

With a fast-paced job and a house in the suburbs of Columbus, Dave Risley is a quintessential Ohio deer hunter. He’s surrounded by an exploding whitetail herd, and hunting seasons are long and generous. But he has little time to get out in the field and even less to devote to his first love, bowhunting.

So Risley hunts with a tool that–with relatively little practice or alteration–allows him consistent harvest success during Ohio’s four-month archery season. Like 140,000 fellow Buckeyes, Risley hunts with a crossbow.

What makes him different is that he is also Ohio’s wildlife management chief, and it’s his job to balance hunting opportunity, wildlife populations and regulation of hunting implements. And Risley is an unapologetic fan of crossbows.

“Crossbows allow hunters to get out in the woods more often, and allow them to be more successful hunters,” says Risley. “For wildlife managers trying to kill as many deer as possible, crossbows have become a necessary tool.”

Crossbows have been legal in Ohio’s archery season since 1984. Every year they grow in popularity, and in the past decade the number of archery hunters who used a crossbow has been about the same as the number who hunt with compounds, recurves and longbows combined. In Ohio’s 2007-08 deer season, crossbow hunters harvested more than 42,000 whitetails, more even than “vertical” bow hunters, who took a record 36,347 deer. In all, archers accounted for more than a third of the state’s 233,000 deer harvested.

More meaningful than their success is crossbow hunters’ participation, says Risley. “Every game agency across the nation is lamenting the loss of hunters and license revenue. By embracing crossbow shooters, Ohio has managed to get and keep hunters, and as a result I’d say the archery hunters in this state have more credibility and clout than ever.”

Ed Wentzler couldn’t disagree more. The legislative director for United Bowhunters of Pennsylvania, Wentzler considers crossbows an unwelcome abomination, and he’s especially rankled that the implements were approved in January for inclusion in the Keystone State’s six-week archery deer season. This fall’s season will be the first to include crossbows, and even before the first bolt is launched, Wentzler is concerned that archery harvest will increase so sharply that gun hunters will lobby to shorten the season to leave more deer for their ranks.

Besides, says Wentzler–a longbow shooter whose last few deer were taken with stone points that he knapped himself–crossbows simply are not bows.

“Archery equipment should be defined as implements that are held by hand, drawn by hand and released by the motion of the hand in the presence of game,” he says. “If you are shooting a crossbow, you are not drawing the string in the presence of game. That alone gives crossbow shooters an unfair advantage. It is not bowhunting.”

Pushing the Regulatory Envelope

If your state wildlife commission or legislature hasn’t yet considered allowing crossbows in your archery deer season, the discussion is coming. In just the past seven years, eight states have opened their regular archery season to crossbows, and in another eight, crossbows are allowed in either a portion of the archery season or are legal for hunters over a certain age.

Crossbows are either outlawed or restricted to the firearms season in another 14 states. In Michigan, with 700,000 deer hunters, the state’s legislature this spring allowed crossbows to be used during the fall archery season in the southern lower peninsula, where the majority of the state’s deer herd lives. New York is also considering crossbow legislation.

What’s behind this sudden embrace of crossbows? Crossbow opponents have pointed to the fact that there is no organized coalition of hunters lobbying state game agencies to allow the implements in archery seasons. Instead, they claim, the push to liberalize equipment regulations to include crossbows is being fueled by the profit motives of the crossbow industry itself, usually over the vocal opposition of traditional bowhunting clubs, which, ironically, galvanized to oppose compound bows a generation ago.

“Follow the money,” says Wentzler. “These new crossbows sell for six to eight hundred dollars a pop. The industry can’t sell them if there’s no season, but once there’s a season, they stand to make a good deal of money. And once people have the equipment and a season, there’s no way they will want to get rid of either.”

Dave Robb, the director of marketing for TenPoint Crossbows, based in Ohio, says it’s not hunters or manufacturers, but state wildlife agencies that are clamoring for crossbows.

“The push for crossbows has come from wildlife professionals faced with serious problems: deer herds that are getting out of control, particularly in urban areas, and the loss of hunters and archers at an incredible rate.”

Indeed, Ohio’s Risley maintains that crossbows are an effective game-management tool in some of the most problematic areas of his state: suburban enclaves.

“We have a lot of suburbs and densely populated townships with intense deer problems,” notes Risley. “A lot of these places will allow bowhunting, but only if hunters can show proficiency. If you don’t pass an accuracy test, you don’t get to hunt there. We get a fair number of hunters participating in those types of seasons only because they can shoot a crossbow accurately.”

Bow/Gun Hybrids

To understand why crossbows create such friction, it helps to understand them in their modern incarnation. If your last experience with crossbows, also called “horizontal” bows by some, was in a high school history book’s description of the Battle of Agincourt or William Tell’s improbable apple-shooting feat, then you’re a few centuries behind the curve.

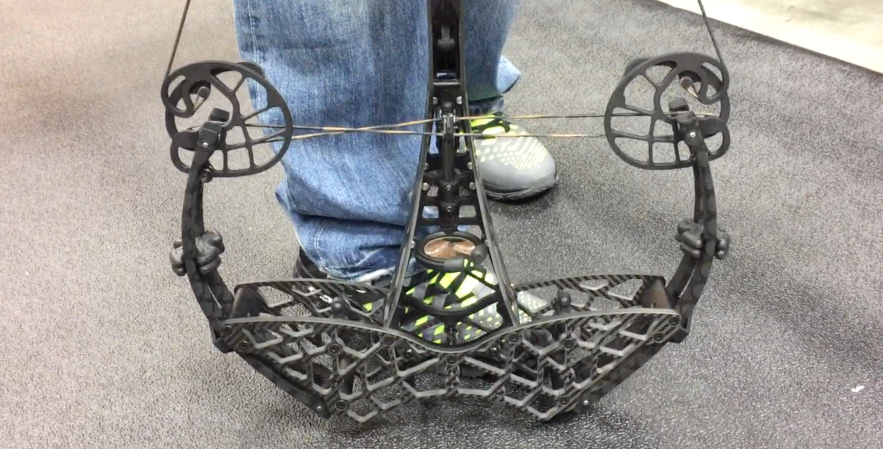

Some attributes of crossbows are timeless: horizontal limbs fastened to a shoulder stock and a mechanism to lock the taut string in a cocked position until ready to shoot relatively short, stocky shafts, called bolts.

But other features are every bit as technologically evolved as modern compound bows. With draw weights in the 175- to 200-pound range, laminated fiberglass limbs and weight-reducing cams, today’s crossbows are capable of flinging bolts between 300 and 375 feet per second, similar to the velocities achieved by the fastest compounds.

Crossbows have attributes borrowed from firearms. Machined triggers, polished-aluminum bolt rails, polymer stocks and telescopic sights all allow crossbow shooters to achieve a level of accuracy in a few hours that traditional bow shooters require weeks or even months to attain.

To crossbow proponents, this out-of-the-box accuracy is an asset.

“Most bowhunters start dropping out of the sport when they reach their 40s,” says TenPoint’s Robb. “Partly it’s physical, but partly it’s because their complex lifestyles don’t leave them the time they had as a younger person to hone their archery skills. Rather than going out there and being irresponsible, trying to kill a deer with a compound bow, they opt out. We give them a tool that, with a minimal amount of practice, allows them to participate and be successful. They still have to locate game and stalk within range, but the main advantage of a crossbow is that it doesn’t require the same amount of time and skill to get and maintain proficiency.”

That ease of use is the foundation for the most intense crossbow opposition. Crossbows represent not only a departure from the method and tradition of bowhunting, but also the ideology of restraint, says Helena, Montana, archer Joelle Selk.

“Bowhunting shouldn’t be simple or easy,” she says. “Most bowhunters understand it is inherently more difficult than other types of hunting, and they intentionally select that path. Because it is difficult, and because success is elusive, when it happens the reward is much greater.”

For Selk, the appeal of bowhunting is its solitude, its requirement to get close to the animal and its demand for precision and commitment. And, she says, in Montana those challenges have been embraced by a growing number of archers. Sales of bowhunting licenses jumped from 21,000 in 2002 to 41,000 in 2007.

“At least here in Montana, we have no bowhunter-recruitment problem,” says Selk.

Where Do Crossbows Belong?

Does this crossbow controversy sound familiar? Replace crossbow with any number of hunting implements–in-line muzzleloaders, illuminated optics, even modern compound bows–and you’ll hear fading strains of the same refrain: Technology will ruin the hunting experience.

So, will it? The question raises an inconsistency that colors this discussion: If crossbows are as effective as the industry and proponents maintain, then they really are “more equal” than conventional bows and perhaps deserve their own season. But if their performance is closer to compounds, then are they really the game-changing tool that proponents celebrate?

It turns out that, from a ballistics perspective, crossbows aren’t that different from modern compound bows. Consider a middle-of-the-road crossbow (175-pound draw, 420-grain bolt pushing a 125-grain field tip) and a moderate compound (75-pound draw, 350-grain shaft tipped with a 125-grain field point).

Based on the bows described, the crossbow generates significantly more energy at the bow, about 115 foot-pounds compared to about 82 foot-pounds for the compound. Shaft velocity is comparable, at about 350 feet per second measured at the bow.

At 10 yards, both shafts will drop about 1 inch. At 20 yards, both drop about 6 inches. And at 30 yards, the distance at which most deer are shot by bowhunters, the compound shaft drops about 17 inches from its zero; the crossbow bolt drops about 15 inches. At 40 yards, the compound drops about 30 inches, the crossbow about 26 inches.

The longer compound shaft tends to fly straighter at longer distances; the heavier crossbow bolt tends to retain slightly more downrange energy than the compound arrow, but sheds its velocity at a faster rate.

It’s the method of release that is starkly, unequivocally the difference between crossbows and traditional bows–even modern compounds that are released with mechanical triggers. The ability to wait at the ready with a cocked and loaded crossbow, which can also be shot from a rest, is so different from pulling back and holding a bow with active arm strength that opponents struggle to classify the former as archery gear.

“Crossbows may have a place in the East with whitetails,” says Steve Sukut, an officer with the Montana Bowhunters Association. In Montana, crossbows are legal only during the firearms season. “But there’s a huge difference between hunting whitetails from a tree stand and hunting elk during the rut. If you didn’t have to draw a bow with an elk looking you in the face, you’d kill a lot more bulls and states would start managing archery seasons the way they do rifle seasons, for high success rates and short seasons.”

Opportunity Vs. Harvest

That potential loss of opportunity alarms crossbow opponents. Traditional bow seasons tend to maximize opportunity with little expectation of harvest. Short, intense firearms seasons, on the other hand, maximize harvest over a relatively brief duration.

Crossbows don’t really fit either expectation, and that’s part of their problem. Where do they belong? Should crossbow hunters have their own season, during which participation and harvest can be balanced? Do they belong with muzzleloaders or with rifle hunters? Or are they sufficiently like compounds and recurves so that crossbows belong in archery seasons? And is there enough time in the fall to create yet another special-weapon season?

“If you have a separate crossbow season, then you take that time away from some other user group,” states Dave Robb. “When you put crossbows in gun seasons, you’re asking archers to be out there with rifles and shotguns, and they don’t like that. Game managers are trying to divvy up the season to various user groups, but maximize harvest. They’re saying they can do that best by adding crossbows to the existing archery season and giving hunters another tool.”

In Pennsylvania, where crossbows had been legal only in the firearms season, Wentzler worries about the biological and social consequences of allowing them in the archery season. “You hear how crossbows will recruit more hunters,” says Wentzler. “It’s nonsense. You will have the same number of hunters–they simply shift seasons.”

And he frets that a substantial percentage of the Keystone State’s one million rifle deer hunters, weary of crowding in the two-week season, will bring crossbows to the six-week archery season.

“With our age demographics, it is not out of the question that an additional 200,000 people could step into our archery season over the next three years,” says Wentzler. “Those aren’t new hunters; they’re displaced hunters. If there’s an overharvest, our archery season–already one of the shortest in the nation–will be shortened even more.”

Crossbows don’t simply force questions about redistribution of opportunity; they also raise questions about whether technologically advanced hunting tools belong in seasons originally reserved for hunters with primitive weapons. Modern compound bows have already raised the stakes. Crossbows simply push the envelope a little further. So what comes next?

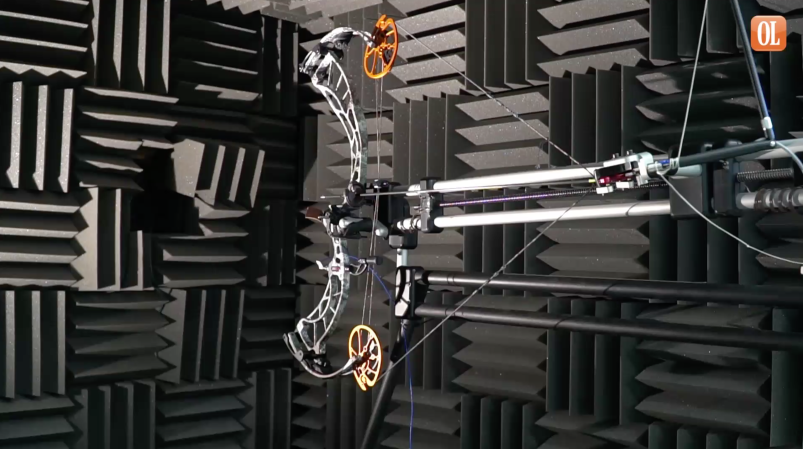

Hunters got a glimpse of the future at January’s Archery Trade Association Show, where PSE Archery unveiled its TAC-15, a horizontal bow upper unit that mates to an AR-15 rifle receiver, turning most tactical rifles into crossbows.

Meanwhile, the compound industry is working hard to produce a bow capable of launching arrows at 400 feet per second. Products of this new arms race are bound to show up in your deer season, whether or not crossbows are allowed.