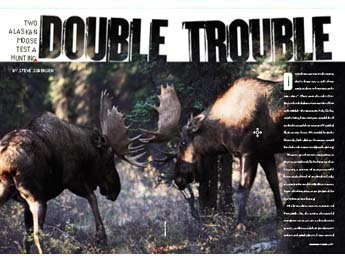

“Don’t shoot a moose in the water, don’t shoot one a mile from camp and never shoot two at the same time.” Those were the rules Gene Bryner handed down to us over breakfast at Fast Eddie’s Restaurant in Tok, Alaska, emphasizing how sorry we would be if we broke any of them on our self-guided, fly-in moose hunt. We would keep the first rule; little did we know we would break the other two-and pay the price.

We were greenhorns in comparison to Bryner, a resident of Alaska for more than 20 years, a veteran of many successful hunts and a friend of my brother Andy, my companion on this trip. Bryner was a fount of information as we prepared for our Yukon moose hunt.

His best advice was to recommend Forty-Mile Air, the service that would transport us to an area abundant in moose, caribou and their predators-wolves and grizzly bears. As we crossed the Alaska Highway back to Forty-Mile Air headquarters, Bryner stressed the “rules” again. “Believe me,” he said, “moose are big. You don’t want to find yourselves alone fifty miles into the bush with a job too big to handle.”

Final Plans

As Charlie Warbelow and his partner, Leif Wilson, readied their small planes, Warbelow said, “There’s a ridge I’ve never been able to land hunters on that’s surrounded by ideal moose habitat. Right now a stiff headwind will allow us to land on one-hundred-fifty feet of it that’s smooth enough not to rip the tundra tires or wreck the tail-dragger wheels on the Super Cubs.”

He then went on to explain, however, that there wasn’t enough ground on the ridge to take off with a load, and that the wind would be different when we left. “You’ll have to clear the rocks to make a runway about four hundred feet long,” he said. “It will mean a day of hard work, but the hunting will be great. Are you up to it?” Given the prospect of hunting virgin Alaska territory, we would have been willing to dam the Yukon River.

Every pound is important when flying Alaskan bush planes. We had already weighed in to certify that we carried less than 50 pounds of equipment. Bush pilots expect passengers to obey rules, and although we might break Bryner’s moose-hunting rules, Warbelow’s were dictated by the harsh Alaska wilderness-and could mean the difference between life and death. Soon we were airborne, headed for the spot we already thought of as Sorensen Ridge. Our little planes hurdled the spruce slopes and tundra-topped mountains. We followed a remote drainage punctuated by beaver dams and lined with willow brush, then descended into a false landing so our pilots could examine the ground before setting down. When the soft, fat tires finally touched the tundra, I knew there was no place on earth I would rather be.

As Warbelow explained where he wanted the landing strip to be cleared, a small band of caribou topped the ridge, signaling the luck we would soon have. A few minutes later our pilots bounced their planes along the rocky tundra and sailed off the edge of the ridge, leaving us alone in the vast Alaska interior.

We quickly set up camp and found a nearby puddle that held some tannin-stained water. We pumped enough through our purifier to fill a collapsible 5-gallon jug, took a drink and began glassing the slopes for big, wide antlers as we took in the boundless beauty of this rugged land.

Sweeping mountainsides were blanketed halfway up by dense scrub spruce, stunted by the weight of the snows of countless frigid winters. In the broad valley, a small stream bordered by strips of yellow willow brush snaked through thick, wet moose habitat. The willow provides moose with a favorite food; the spruce offers plenty of cover.

Our binoculars soon revealed five good bulls, their ivory antlers dotting the landscape a mile away. In vivid contrast to the dark green spruce, the massive antlers almost shone and made bulls much easier to spot than cows. The lasaid we could not hunt on the day we flew in, so we relaxed and watched the bulls feed. Antler requirements for a legal bull in this hunting unit were 50 inches minimum width, or at least four brow tines on one side. Through our spotting scope, we considered which ones might be candidates to wear our tags.

It had been a long day, and we were on top of the world. Even though we hadn’t spent much energy, anticipation had tired us. So we fired up our little camp stove, cooked and ate our dehydrated dinners and crashed.

First Blood

Early the next morning Andy zipped open the tent fly and immediately spotted two wolves on a mountain about three miles away. Because the high wolf population is a big threat to moose and caribou calves in this hunting unit, no tags are necessary to shoot them. The wolves seemed headed for the back side of the mountain, where we were camped, so we decided to start our moose hunt by going after a wolf hide. We quickly packed everything we would need for a day away from camp and set out on an impromptu expedition, forgetting about our quest for trophy moose for the moment.

We had gone about 300 yards when Andy turned for a backward look at our campsite. A small band of caribou was crossing the gravel tundra that would become our landing strip. The little herd held one magnificent bull, and it was heading directly toward us.

Andy had our only caribou tag, so I whispered, “Get your gun ready.”

With rifle strapped to his pack frame, he replied, “What about the wolves?”

“Forget the wolves. You have a nice caribou begging you to shoot him!”

“This is the first day,” he said. “What if we see a bigger one later?”

“Get your pack off and use it as a rest. And give me your video camera!”

The animals closed to a range of about 80 yards. Andy’s hesitation gave them opportunity to worry. They acted fidgety, shuffling their feet and pacing, looking back and forth and bobbing their heads like nervous whitetails.

Finally, Andy lit the fire in his .280 Remington and a cloud of steam erupted from the exit wound in the bull’s off side. The animal staggered, and his entourage looked confused. He turned to run, but his lungs couldn’t fuel his legs. Finally, he stumbled, then rocked and fell, dead before he hit the ground. Serendipity on day one of our moose hunt delivered Andy a handsome bull caribou. It was the biggest we would see all week.

Moose on the Move

While we spent Saturday hauling caribou meat, our moose were on the move. On Sunday we couldn’t locate them on the slope opposite our campsite, so we hiked a mile up the ridge. From there our binoculars covered another mile to the head of the valley, where we found all five, plus a sixth with monstrous antlers. We estimated them at nearly 70 inches across. He was protecting two cows from the lusts of the other five. Our problem: He was two miles from our campsite. Remembering Bryner’s rule, we knew this was a challenge too daunting. Besides, at the head of the valley the slope was too steep to climb down. We had no choice but to watch and hope for good bulls closer to camp the next day.

Early Monday morning we again hiked up the ridge and glassed the opposite slope. Our binoculars revealed two of the bigger bulls, apparently driven from the giant bull’s harem. Still, they were more than a mile from camp. While we studied them they rested, but by mid-afternoon they began meandering around in the spruce brush, clanking antlers and browsing on willow. With their attention on their immediate surroundings, we saw our opportunity to begin the stalk.

We descended through a quarter mile of rockslides and another quarter mile of thick spruce. We shed our packs, crossed the stream and took a position downwind of the bulls. Andy volunteered to do the calling and offered me the first shot, so I set up 75 yards nearer the animals.

Minutes after Andy began scraping brush and moaning through the moose call, I spotted a flash of antlers in the distance. I heard the moose thrash some trees, then splash through the rocky stream below us. Convinced they were trying to circle downwind, I hustled back to Andy. The bulls suddenly appeared in the one open spot across the stream, 200 yards away. I sent three Nosler 175-grain Partition bullets at one from my 7mm Remington Magnum. Andy fired at the other. We could hear the watermelon sound of our bullets punching into their big bodies.

Both behemoths collapsed, hidden in the thick spruce tangle. We hurried across the stream, then slowed to a cautious pace. I was 10 yards from my moose when Andy shouted, “To your left!” I turned as the animal roared. He stomped his front hooves into the ground, raised his head and rocked his imposing antlers toward me. Of my first three shots, two had hit his rib cage dead center; the third had broken his spine. I now shot him a fourth time, hitting him in the neck and finishing him. Andy’s bull lay dead 15 yards away.

It was Labor Day, and the work we faced gave the words new meaning. Bryner was right. One moose is huge. A mile from our campsite with two enormous bulls, we had broken two of Bryner’s cardinal rules and we would suffer for it. Three thousand pounds of dead moose is a staggering task. We had to separate the meat from both hulking carcasses and pack it a mile uphill, fighting our way through the spruce jungle and rockslides, across the spongy moss and blueberry slope to the landing strip that still needed to be built. Our moose hunt was doubly successful, but doubly difficult, and we knew we couldn’t claim success until the meat and antlers were on the mountaintop.

After snapping a few pictures, we found out how thick a moose hide is. Then we realized how hard a moose is to roll over-even after one side has been removed. We also discovered how heavy a single moose quarter is. We endured the backbreaking work of carrying 10 meat-laden packs up the rugged mountainside. There is little else to say about packing moose meat, except that on Friday night our exhausted bodies collapsed.

How Did We Do It?

Bryner’s rule against shooting two bulls together was good counsel. Bad weather, accident or injury could have made our task impossible. And it’s no wonder he warned against harvesting a bull so far from camp. All but the most dedicated hunters will shrink at the prospect of packing meat up the mountainside for four days.

Now that the hunt is over, we ask ourselves how we managed to accomplish what we did. We had been smart enough to spend months getting our legs and lungs in shape. But even our extensive preparation would not have been enough if other things had not fallen into place.

First,set up 75 yards nearer the animals.

Minutes after Andy began scraping brush and moaning through the moose call, I spotted a flash of antlers in the distance. I heard the moose thrash some trees, then splash through the rocky stream below us. Convinced they were trying to circle downwind, I hustled back to Andy. The bulls suddenly appeared in the one open spot across the stream, 200 yards away. I sent three Nosler 175-grain Partition bullets at one from my 7mm Remington Magnum. Andy fired at the other. We could hear the watermelon sound of our bullets punching into their big bodies.

Both behemoths collapsed, hidden in the thick spruce tangle. We hurried across the stream, then slowed to a cautious pace. I was 10 yards from my moose when Andy shouted, “To your left!” I turned as the animal roared. He stomped his front hooves into the ground, raised his head and rocked his imposing antlers toward me. Of my first three shots, two had hit his rib cage dead center; the third had broken his spine. I now shot him a fourth time, hitting him in the neck and finishing him. Andy’s bull lay dead 15 yards away.

It was Labor Day, and the work we faced gave the words new meaning. Bryner was right. One moose is huge. A mile from our campsite with two enormous bulls, we had broken two of Bryner’s cardinal rules and we would suffer for it. Three thousand pounds of dead moose is a staggering task. We had to separate the meat from both hulking carcasses and pack it a mile uphill, fighting our way through the spruce jungle and rockslides, across the spongy moss and blueberry slope to the landing strip that still needed to be built. Our moose hunt was doubly successful, but doubly difficult, and we knew we couldn’t claim success until the meat and antlers were on the mountaintop.

After snapping a few pictures, we found out how thick a moose hide is. Then we realized how hard a moose is to roll over-even after one side has been removed. We also discovered how heavy a single moose quarter is. We endured the backbreaking work of carrying 10 meat-laden packs up the rugged mountainside. There is little else to say about packing moose meat, except that on Friday night our exhausted bodies collapsed.

How Did We Do It?

Bryner’s rule against shooting two bulls together was good counsel. Bad weather, accident or injury could have made our task impossible. And it’s no wonder he warned against harvesting a bull so far from camp. All but the most dedicated hunters will shrink at the prospect of packing meat up the mountainside for four days.

Now that the hunt is over, we ask ourselves how we managed to accomplish what we did. We had been smart enough to spend months getting our legs and lungs in shape. But even our extensive preparation would not have been enough if other things had not fallen into place.

First,