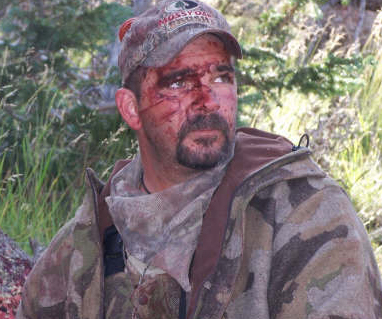

When Greg Matthews glimpsed a large brown animal moving through the timber on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, he snapped the release onto the string of his bow. Forty yards behind him, Greg’s brother Roger was blowing a moose call, hoping to coax a bull into bow range. As the dark form moved into the open, however, Greg realized he had a real problem. It wasn’t a moose that had responded to the call, but a grizzly sow with two sub-adult cubs behind her.

Greg had wanted to shoot a moose with his bow, but he had brought along his .300 Winchester Magnum rifle just in case. Now that rifle, loaded and safetied, was leaning against a tree beside his right leg. The bear stopped at the junction of three game trails, tilting her nose into the air as she tried to locate the moose. As a firefighter with two decades of service and a retired Air Force member, Greg had experience in tense and dangerous situations. He resisted the urge to remain still in hopes that the bear would just pass by. Because if she did, she would likely walk directly toward Roger. Greg was downwind and the bear hadn’t yet seen or heard him, so he slowly put down his bow, reached for the rifle, and lifted it into position.

The sow padded closer, only 20 yards away now. Greg tried to scare her off.

“Hey, bear!” he said firmly. The words were barely out before the grizzly charged.

THE MAULING

Greg fired when the bear was about 8 feet away, but that didn’t stop her. The sow hit him with such force that she careened over him. She instantly turned, and with her paws on his shoulders, bit down into Greg’s neck, face, and cheek. The sow’s canine teeth penetrated his gums. Greg turned his head away, and the bear put her mouth over the top of his head. Greg knew if the sow managed to anchor her teeth into his skull, he was a dead man. But his rifle had been knocked away during the charge. So he swung his fist up into the bear’s nose. She moved away from his head, and Greg tried to punch the sow again, though this time she clamped down on his forearm, driving her teeth through the muscle and flesh.

The bear let go of his arm, and in a moment of clarity Greg noticed a warm pool of liquid forming on his chest; he knew he was losing blood fast. His only hope was to protect his vulnerable head, neck, and chest, so he rolled over onto his stomach and laced his fingers over his neck.

Greg realized that he couldn’t see. He didn’t know if the blindness resulted from blood in his eyes or shock. The bear tried to wrestle Greg out of his defensive position by clawing at his head, opening a 7-inch wound that stretched from above his ear down to his the base of his neck.

“I remember the smell,” Greg says. “That bear smelled awful, like rotten, musty meat. Her breath was right in my face.”

Greg spread his legs so he had leverage to prevent the bear from flipping him over. In frustration, the bear circled Greg, biting his legs, trying to drag him into the alders.

“I knew this was it,” Greg says. “I knew I was fighting for my life. If she got me into the thick alders, it would be over.”

Pain seared through his body, but he resisted passing out. His vision was still gone, and all he could hear was a sharp ringing. When the bear sank her teeth into his hip, he instinctively swung his knee into the bear’s face. On his second attempt she bit through his leg.

Then, over the ringing in his ears, he heard Roger’s voice, shouting in the background. Now, the bear was gone, huffing and charging at Roger just the way she had blitzed Greg. Roger, too, had a .300 Winchester Magnum, and as the sow rushed through the alders, it offered Roger his first clear shot. The shot stalled the bear, but in an instant she was up on her hind legs, towering above him. He fired again, striking the bear in the neck before she disappeared into the alder thicket, popping her jaw and growling.

FIGHTING TO SURVIVE

Roger was terrified by the sight of his mangled brother.

“I think I’m dying,” Greg told Roger.

“Tell me what to do,” Roger shouted. That’s when Greg’s first-responder training kicked into gear. He knew he was losing blood, and he still couldn’t see, so he coached Roger on administering first-aid. Greg asked his brother to describe the wounds, focusing on the most severe first. Roger replied that Greg’s chin and neck were torn apart and bleeding badly. Both men had shemaghs—head wraps commonly worn by soldiers in desert environments. Based on the description of his wounds, Greg blindly tied his own shemagh into a bandage and had Roger wrap it around the wounds on his face.

Greg fought off thoughts about dying and blocked out the panic. Instead, he focused only on the first-aid process and solving the problems at hand. As a first responder, he had coached countless trauma victims from the brink of death, and now he was repeating those same common phrases of encouragement to himself: Stay awake. Stay focused. You’re going to be okay. Don’t panic, it won’t do you any good.

Time was of the essence, and Greg knew it. He felt sick and cold, signs of shock. Roger surveyed the rest of Greg’s wounds. There was a quarter-size hole in his arm, but the tight-fitting jacket he was wearing acted as a pressure bandage. The leg wound was bad, but the leg didn’t seem broken. After he finished tending to the wounds, Greg rolled onto his side. He felt dizzy and sick, and was struck by an overwhelming urge to rest. But he fought against it. Experience told him that his body was trying to deceive him. Can’t rest now. Got to keep moving.

300_ Winchester Magnum rifle Matthews had with him. Photographs courtesy of Greg Matthews._

Roger cut away any clothing that could get caught in the brush, and Greg wiped his eyes with a rag. His vision returned, but it was dim. Greg began the march down to their boat on Skilak Lake. Roger followed, 8 feet behind his brother with his rifle ready, in case the grizzly decided to follow them. It was a mile hike back to their boat.

Halfway to the lake Greg went down, woozy and nauseous. Roger stayed with him, encouraged him, and prayed over him. Greg thought about nothing except reaching the beach on Skilak Lake. That was his purpose now. He trudged on until he reached the beach and then collapsed on a spit of gravel and sand.

Greg instructed Roger to grab the trauma kit from the boat, and they used bandages to cover more wounds. Greg also had Roger bring over every piece of clothing in the boat and cover him. Greg had never been so cold.

Through the fog of shock, Greg heard voices. Three Skilak anglers had idled their boat to the beach and now stood, faces white, looking at Roger and the bloodied Greg. Roger ordered them to drive to the middle of the lake—7 miles—to where there was cell service. They rushed out to call for help.

Hours later, the still of the Alaskan night was cut by the whir-whir-whir of an incoming helicopter. Roger set fire to a pile of tree limbs that he had gathered on the beach and doused in gasoline fetched from the boat. The fire erupted and Roger shot a flare into the night sky. The helicopter made a high approach followed by a low pass before it set down near the water’s edge. Greg’s fight to survive was finally won.

READ MORE

One Wrong Step

Alone, severely injured, and 10 miles into Idaho backcountry, elk hunter John Sain had a decision to make: end the suffering or crawl for help

Alone, severely injured, and 10 miles into Idaho backcountry, elk hunter John Sain had a decision to make: end the suffering or crawl for help Vincent Soyez

The Crash

Sixteen-year-old Autumn Veatch, the sole survivor of a remote plane wreck, rescues herself

Eye of the Tiger

Hawaiian spearfisherman Braxton Rocha fights back fear and swims for his life after a shark attack

Your Brain on Survival

Here’s what happens when the body shifts into survival mode, and how you can stay in control