A silver frost still blanketed the grass when we saddled up, waved goodbye to my wife, Peggy, and began moving up the mountain behind our Wyoming sheep camp. An hour later we had tied our horses 200 yards from the top, then climbed through the rimrock to a relatively flat ridge where we could glass the mountain that stood to the east of us above Caldwell Creek.

My guide and youthful companion, Mark Condict, had bounced upward not unlike a mountain goat while I had huffed and puffed my way along. I was winded and it felt good to sit back against a rock, catch my breath and view the distant mountains of the Washakie Wilderness Area.

All around us the Absaroka Rockies were piled one on another with a light glaze of snow dappling the peaks. On the western horizon loomed the jagged silhouette of the Wind River Range, still shrouded in the purple mists of early morning. The September sun was just beginning to rise. Amid the spruce, fir and white pine, pockets of aspen began to glow with a blaze of bright color that spread as light found them. Dark, shadowed canyons rimmed with gray rock fell sharply away to the serpentine creek far below. The sound of white-water rapids ebbed and flowed as wind currents fell and rose beneath us.

This magnificent area is prime country for various big game. The story of a sheep, elk and grizzly hunt here, written by C.E. Sykes and titled “Hitting the High Spots in Wyoming,” was reported in the August 1919 issue of outdoor life. Ned Frost, a pioneer Wyoming sheep-hunting guide, was outfitter for that memorable hunt.

When my guide’s father, Win Condict, was a youngster, he guided for Frost and eventually bought his outfit. After an illustrious career, Win retired a number of years ago. Now Mark and his wife, Val, manage this historic operation as Grand Slam Outfitters in Saratoga, Wyo. Mark has guided hunters to sheep, elk, deer, lions and bears in this area for 26 years.

Below us in a golden meadow a couple of miles away we watched a large herd of elk. It contained an old monarch six-pointer with antlers that brushed his hips when he bugled. I was looking at elk and assumed Mark was. Then he quietly said, “I see three rams.”

As Mark set up his spotting scope for a more serious look, he directed my attention to a narrow park at the edge of the timberline on the mountain across Caldwell Creek. Through my binocular I picked out two half-curl rams near the base of a rocky cliff. Presently a third ram fed into the open, and it was obvious he deserved closer inspection. His horns had good mass and appeared to be almost full-curl.

We began our stalk at mid-morning after the rams had bedded down. The afternoon was almost spent by the time we had made our long ride and tied our horses just under the rimrock. Carefully we picked our way downward, searching for the narrow park where hours earlier we had glassed the rams.

We had descended perhaps a thousand feet when Mark whispered, “This is the place. Let’s ease down and check for our rams.”

We inched forward through scattered timber and carefully moved to the brink of the cliff below, which the rams had bedded. They were gone. We figured they were up and grazing again so we sat down and began to glass the slope below. Presently we saw a ram walking through the timber 200 yards downhill. Mark evaluated the sheep while I quietly chambered a round into my .308 Winchester Model 70. “That’s our bighorn,” Mark said. “A seven- or eight-year-old, decent bases and almost full-curl. He’s no record-book ram but he’s a fine trophy.”

The ram was moving toward an open gap in the treetops. I had waited a long time for this moment.

In 1973, I drew a coveted desert bighorn permit in Nevada on my first application and subsequently took a good ram with the late and legendary sheep guide Jerry Hughes (“Rug Mountain Ram,” May 1975). In 1981 I took a ophy Dall ram in Alaska (“Anniversary Hunt,” outdoor life Hunting Annual, August 1982). But for 22 years I had applied unsuccessfully for a Rocky Mountain bighorn permit in a number of states. Finally the Wyoming permit had arrived in the mail and now I waited to put my crosshairs on a bighorn.

“He’s coming into the open,” Mark said. “Get ready.”

There was no place to take a rest so I ran my arm through the rifle’s sling and eased off the safety. Adrenaline jolted my system and I worked to steady my nerves.

The ram ambled into the one clearing where an unobstructed shot was possible. I put the crosshairs slightly below the center of his shoulder and touched the trigger. At the impact of the 165-grain bullet the ram lunged forward, then tipped over.

We both let out a war whoop. “Fine shot,” Mark said as he grinned and pumped my hand.

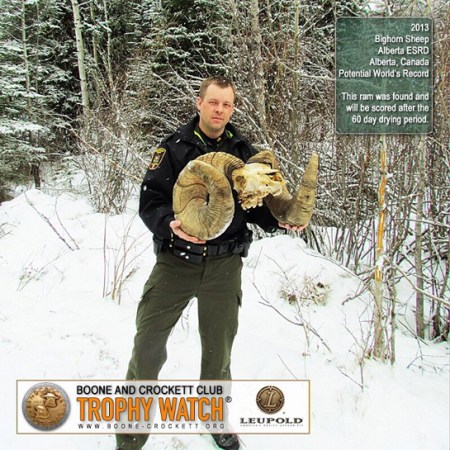

The ram was a handsome eight-year-old. The bases of his horns were 15 inches and he measured over 34 inches around the curls. He was blocky and heavily built. His pelt was brownish-gray with a cream-colored muzzle.

After we celebrated for several minutes Mark went to fetch the horses while I field-dressed the ram. Then I sat back and ran my hands over those beautiful horns. As I savored the moment and thought about what a thrilling day it had been, little did I realize that a perilous adventure was still to come our way.

By the time Mark returned with our horses the sun had slipped behind the ridges. I suggested that we pose the ram, then return at dawn for an extended photo session before packing it out.

“We can’t do that,” Mark said. “It won’t be here at dawn. If the grizzlies don’t get it, the coyotes will.”

I told him I thought the chances of a grizzly finding my ram were remote, and as for the coyotes, I would leave my undershirt on the carcass and urinate on the ground around it. This had worked in the past to keep predators off game I had left overnight.

Mark reminded me that when we had set our camp we had cached our food 20 feet up a tree. “That wasn’t for show,” he drawled. “There are a good many bears here and your plan won’t keep a griz off your ram.”

Despite his objections I was determined to get photos in good light and insisted we leave the ram. We walked our horses several hundred yards down the rugged slope until we came to a bench. The day had been tough on my old bones and I suggested we mount up and ride while we could. We hit the saddles and rode side-by-side for a short distance. Suddenly, 30 yards off to our right front, a bear cub stood up in the brush.

“Look at that bear!” I said.

At the sound of my voice the cub broke and ran across our front. As it passed before us a sow bear rose from the undergrowth. She was huge, with a silver hump on her back. Instinctively I exclaimed, “Grizzly!” The bear’s head turned toward us and her jaws snapped. In the next instant she came in full-charge with every hair bristling and with an ominous roar rumbling from deep in her chest. It was a terrifying spectacle.

Mark was facing the bear and as she rushed in his horse spooked and wheeled into mine. My horse tried to turn but a fallen tree on our left blocked his way. Then he jumped backward into the path of the sow. With jaws snapping she turned from one horse to the other.

As we fought to control our panicked mounts I tried in vain to pull my rifle from the saddle scabbard. Fear welled up in my throat, for I knew if my horse threw me the grizzly would be on me in an instant.

Just then the cub came back running across in front of us and the sow turned and charged after it. As the cub disappeared into a tangled thicket on our right the protective grizzly turned her head and glared at us.

Still struggling to control my groaning horse, I managed to jerk my Winchester from the scabbard and chamber a round. A second later she came for us again in great bounding leaps — woofing as she approached. I tried to shoulder my rifle, knowing all the while there was little chance I could hit her if the situation demanded it. I was working just to stay in the saddle on my terror-stricken horse.

Luckily the charge was a bluff and the grizzly pulled up five yards away. She growled and snapped her jaws and swung her great head from side to side. Then she simply turned away and trotted into the thicket where her cub had gone.

Mark shouted, “Go, go!” and we kicked our horses and plunged out through the timber. As we galloped away we passed a dead cow elk. We had stumbled upon grizzlies on a kill and had managed to separate a sow from her cub. It was a very perilous incident but neither of us was hurt. Had we not been mounted there could have been deadly consequences.

We worked our way off the mountain in the fading twilight and I occasionally looked back to see if the sow would make another run at us. When we struck the river in the bottom of the gorge I reined up and called to Mark, “Is there any way we can loop up and get my ram off the mountain?”

“In the dark?” he answered quietly. Then he just turned his horse for camp and moved off. I was grateful he didn’t add, “I told you so.”

Peggy was waiting in the cook tent when we rode into camp. The lantern light illuminating the walls of the tent and the delicious smell of camp cooking held no magic for me that night. Miss Peg listened as we recounted the events of the day. She was delighted that I had at last taken the bighorn I had longed for through all those years but was horrified to learn I had left it on the mountain.

“Heavens!” she said. “I cannot believe that after waiting all this time you just left your ram for the bears.”

“Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time,” I mumbled.

That night I tossed and turned through the long hours, the terror of a charging grizzly lost in the vision of bears gnawing on my precious Rocky Mountain bighorn. Would they leave an elk for a ram?

At dawn we picked our way back up the mountain. At last we struck the top of the cliff where I had made the shot and there below where we had left it — all posed for photos — was my bighorn, untouched by grizzlies!

Eventually we loaded our packhorse with the ram’s head, cape and meat and started down the mountain. It was mid-afternoon when we rode triumphantly into camp to the delighted cheers of Peg and Carol the cook.

It was cold and starry that last night in the mountains. We sat around the campfire, toasting the ram and feasting on one of the world’s most exotic and delicious meats: tenderloin of bighorn.

By and by the firelight slowly died away as we talked about great sheep hunts of the past chamber a round. A second later she came for us again in great bounding leaps — woofing as she approached. I tried to shoulder my rifle, knowing all the while there was little chance I could hit her if the situation demanded it. I was working just to stay in the saddle on my terror-stricken horse.

Luckily the charge was a bluff and the grizzly pulled up five yards away. She growled and snapped her jaws and swung her great head from side to side. Then she simply turned away and trotted into the thicket where her cub had gone.

Mark shouted, “Go, go!” and we kicked our horses and plunged out through the timber. As we galloped away we passed a dead cow elk. We had stumbled upon grizzlies on a kill and had managed to separate a sow from her cub. It was a very perilous incident but neither of us was hurt. Had we not been mounted there could have been deadly consequences.

We worked our way off the mountain in the fading twilight and I occasionally looked back to see if the sow would make another run at us. When we struck the river in the bottom of the gorge I reined up and called to Mark, “Is there any way we can loop up and get my ram off the mountain?”

“In the dark?” he answered quietly. Then he just turned his horse for camp and moved off. I was grateful he didn’t add, “I told you so.”

Peggy was waiting in the cook tent when we rode into camp. The lantern light illuminating the walls of the tent and the delicious smell of camp cooking held no magic for me that night. Miss Peg listened as we recounted the events of the day. She was delighted that I had at last taken the bighorn I had longed for through all those years but was horrified to learn I had left it on the mountain.

“Heavens!” she said. “I cannot believe that after waiting all this time you just left your ram for the bears.”

“Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time,” I mumbled.

That night I tossed and turned through the long hours, the terror of a charging grizzly lost in the vision of bears gnawing on my precious Rocky Mountain bighorn. Would they leave an elk for a ram?

At dawn we picked our way back up the mountain. At last we struck the top of the cliff where I had made the shot and there below where we had left it — all posed for photos — was my bighorn, untouched by grizzlies!

Eventually we loaded our packhorse with the ram’s head, cape and meat and started down the mountain. It was mid-afternoon when we rode triumphantly into camp to the delighted cheers of Peg and Carol the cook.

It was cold and starry that last night in the mountains. We sat around the campfire, toasting the ram and feasting on one of the world’s most exotic and delicious meats: tenderloin of bighorn.

By and by the firelight slowly died away as we talked about great sheep hunts of the past