Editor’s Note: This post is a revision of the original blog entry, which we published last Thursday and then took off-line in order to improve the reporting. Mainly, we wanted to get the perspective of the Huron Mountain Club, and to verify a number of details such as the size of the club, its membership, and the claim that it has hired off-duty law enforcement officers to patrol the Salmon Trout River.

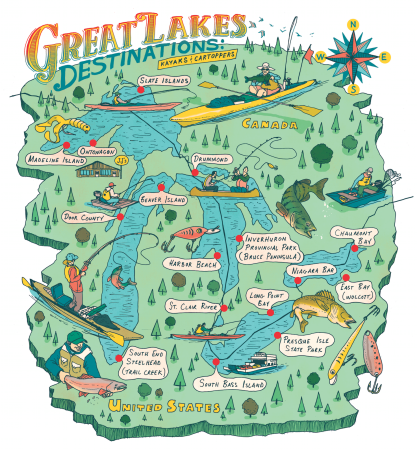

This is an access story that has it all: a disputed law, a river with a sacred variety of trout and an exclusive club that is attempting to privatize a road, a river, and even the law to defend what they say is their own property. Here’s what’s at stake.

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is what trout fishing was meant to be. It’s a vast expanse of conifer nastiness laced with rivers, creeks and streams. Within you will find some of the finest, purest native brook trout fishing in the country. You won’t find a ton of big fish but there are some. But I’ve never really had much to complain about when it’s quite possible to hook 100 colorful, native brook trout in a day. Size be damned.

It is a rare place where you can fish darn near anywhere you want to without worry of trespass, snobbery or other such inconveniences. The Upper Peninsula has an enormous amount of public lands ranging from state-owned parcels to National Forest to Commercial Forest Act properties that allow public access.

Michigan is a state that allows public fishing access to any “navigable” water. What does that mean? Well here’s the exact legal language:

A navigable inland stream is (1) any stream declared navigable by the Michigan Supreme Court; (2) any stream included within the navigable waters of the United States by the U.S. Army Engineers for administration of the laws enacted by Congress for the protection and preservation of the navigable waters of the United States; (3) any stream which floated logs during the lumbering days, or a stream of sufficient capacity for the floating of logs in the condition which it generally appears by nature, notwithstanding there may be times when it becomes too dry or shallow for that purpose; (4) any stream having an average flow of approximately 41 cubic feet per second, an average width of some 30 feet, an average depth of about one foot, capacity of floatage during spring seasonal periods of high water limited to loose logs, ties and similar products, used for fishing by the public for an extended period of time, and stocked with fish by the state.

It’s a law that is both clear and vague at the same time. And it has come under scrutiny all across the country.

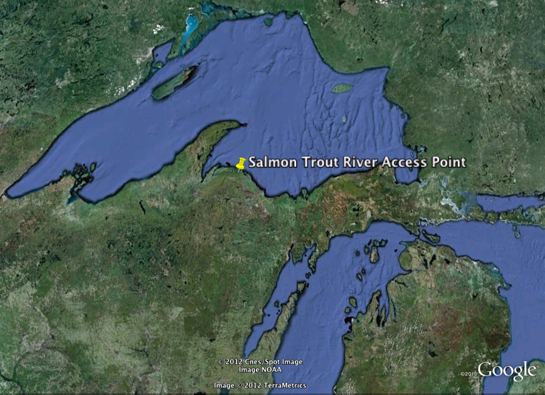

Located in Marquette County, the Salmon Trout River is home to one of the last native populations of coaster brook trout in the country and, in the opinion of the Michigan Supreme Court, meets the description of a navigable river and thus is open to public fishing.

The Huron Mountain Club, a private club reported to encompass somewhere between 10,000 to 20,0000 acres, does not dispute that fact. It does, however, feel that ownership of that navigable river lies with the property of the club, which was founded in 1889 to conserve what at the time were diminishing natural resources of the Great Lakes region.

There are only two viable public accesses along the Salmon Trout, the mouth of the stream along Lake Superior’s southern shore or at a bridge along Marquette County Road KK — a bridge on a road that the Huron Mountain Club claims it once owned and will soon again.

The Huron Mountain Club, according to current member Harry Campbell, has 50 “regular” members and 180 associate members. The club’s IRS Form 990 filing from 2010 reported membership dues in 2010 of $1,441,230 with total member-related revenues of just under $2.8 million. How exclusive is it? Henry Ford waited more than 10 years before he was granted membership.

For decades, the Huron Mountain Club has attempted to keep the public off the water by arguing that there is no public access available to the stream at the bridge. But past statements and rulings from local and state officials, including Michigan’s attorney general, have kept the access at the bridge open.

Despite those legal rulings, the Huron Mountain Club has consistently claimed that public access is not available. In February of 2009, the Club used a road abandonment process to claim possession of County Road KK and the bridge anglers use to access the river from the Marquette County Road Commission.

Why would the club spend so much money and energy to control access to a public river? Campbell says it’s to protect the fragile fishery and a study funded by the Club’s Huron Mountain Club Wildlife Foundation on coaster brook trout.

Fishing by the general public is a deterrent to recovery because so many anglers use live bait, coasters are very easy to catch when using live bait, and too many visiting anglers kill their limits whenever they can,” Campbell wrote in an e-mail. “The Club’s objective is not to deny legal public access to a navigable river, but to use any legal means at our disposal to help restore a very rare and endangered sub-species of native brook trout – which are alive today only because of the Huron Mountain Club’s ongoing efforts to protect and preserve them.”

In April of 2011, the Michigan Court of Appeals considered a June 2010 decision by Marquette County Circuit Court Judge Thomas Solka ruling that the road abandonment process was not conducted properly and that the Marquette County Road Commission still retained the road and the bridge thus preserving public access to the river.

That appeal process was stalled until March of this year, when the Road Commission was ordered to pay the Huron Mountain Club nearly $141,000 in damages for work done on the bridge and a 32-acre parcel that serves as a turnaround on the road.

With the damages settlement out of the way, the Huron Mountain Club refiled its appeal on March 13, asking that the ruling be overturned and ownership of the bridge transferred to them. And according to reports from anglers, the club stepped up its efforts last fall to keep the public from accessing the river by hiring off-duty county police officers to patrol their property and the publically accessible river.

The Marquette Mining Journal has been the primary media outlet following the issue and it’s been more dramatic than daytime TV in the last few months.

In January, angler Donn Collins of Negaunee told the county board that security guards, deputized by Marquette County sheriff Michael Lovelace and working for the club, hassled fishermen on many occasions at the river after they legally gained access at the county bridge. The anglers claim the deputized guards threw sticks in the water to scare away fish, demanded the anglers show them their fishing licenses and identification and threatened to confiscate their gear.

So how is it that a private club is hiring county-paid police officers to serve as their own personal pinkertons?

Campbell says the club does so to ensure it receives the best possible monitoring.

” The club employs off-duty, deputized sheriffs because they are trained law enforcement officers with an average of 20 – 25 years of law enforcement experience, who perform their duty with a high degree of professionalism — which is only one reasons so many deputized sheriffs are employed by private organizations and land owners all over Michigan,” he wrote.

In a letter to the Marquette County Board of Commissioners in March, Sheriff Lovelace claimed his decision to deputize sheriffs for private use doesn’t concern the board.

“The aspects of deputization by the sheriff rests solely with the sheriff and not the county board of commissioners or Mr. Donn Collins,” Lovelace wrote. “The board has no role or say in the day-to-day operational functions of the Office of Sheriff and cannot dictate who the sheriff deputizes. Period.”

But it is the higher courts that have the say when it comes to the issue of the public’s right to access a public waterway.

In all instances, the courts have determined that the Salmon Trout River is a public, navigable river and that the bridge on the public road is a legal public access point.

Perhaps the Huron Mountain Club will win its appeal and regain ownership of County Road KK and the bridge that anglers use to access the public river. Perhaps it won’t. But, for now, the law stands.

And the law says we can fish.