Pop quiz: If a carpenter in San Juan County, NM, purchases a New Mexico fishing license for $25, and a hedge fund manager from Connecticut purchases a lifestyle ranch on the San Juan River for $6.8 million, which purchaser acquires constitutional protection of his individual rights?

A) Neither. Rights can’t be bought or sold in the United States. That’s why they’re called rights.

B) The “rancher,” by virtue of the Golden Rule. He’s got the gold, so he makes the rules.

C) Rights? Who cares about rights when the government is a gang of incompetent freedom-haters mismanaging New Mexico’s resources? Private property trumps public access.

If you answered A, pat yourself on the back. I applaud your idealism and your faith in American democracy. You obviously paid attention in high school civics class.

If you answered B, award yourself five points. You’ve continued to pay attention since high school, and you’ve picked up on some alarming patterns in our electoral politics.

If you answered C, congratulations! You may have a future in the New Mexico state legislature.

Unfortunately, this quiz is not a purely academic exercise. The answers have real-world impacts on New Mexican anglers.

In case you missed it, in April 2014 outgoing New Mexico Attorney General Gary King issued an official opinion that “…a private landowner cannot prevent persons from fishing in a public stream that flows across the landowner’s property…”.

He cited as evidence a 1945 Supreme Court case, State Game Commission v. Red River Valley Company, in which the high court decided, “The small streams of the state are fishing streams to which the public have a right to resort so long as they do not trespass on the private property along the banks.”

Repeated attempts to overturn the ruling, noted Attorney General King, had all failed. In fact, the justices later added emphasis; “The sovereign power itself, therefore, cannot, consistently with the principles of the law of nature and the constitution of a well ordered society, make a true and absolute grant of the waters of the State divesting all the citizens of a common right. It would be a grievance, which never could be long borne by a free people.”

Rank-and-file anglers celebrated the AG’s opinion statewide. For generations they’d been excluded from touching bottom anywhere a river crosses private property. They assumed that such an unequivocal stance by the state’s highest court ensured the restoration of their wading rights.

But the New Mexico Game Commission–a seven-member committee of gubernatorial appointees–responded with conspicuous silence and continued enforcement of the unconstitutional status quo.

A year of increasingly heated advocacy has ensued in the year since we covered the topic here. The New Mexico Wildlife Federation, American Canoe Association, America Outdoors Association, American Whitewater, Adobe Whitewater Club, New Mexico Chapter of Trout Unlimited, dozens of small businesses, and scores of private citizens demanded that regulations be made to reflect the law.

Meanwhile Soaring Eagle Lodge LLC., Chama Troutstalkers LLC., Z&T Cattle Company, and the New Mexico Council of Outfitters and Guides sued the state to stop it from doing so. In a bizarre and particularly galling twist, the State Game Commission filed an amicus brief supporting the lawsuit in which they were named as defendants. The Game Commission essentially chose to sue itself instead of honoring the established rights of the sporting public.

Then the legislature stepped into the fray. On March 20, 2015, the second-to-last day of the legislative session, 32 state representatives voted to deny anglers the rights afforded them by their state’s constitution. Senate Bill 226 passed by a single vote.

The New Mexico Wildlife Federation’s Joel Gay summed up the sporting public’s frustration, “We don’t have a lot of water here in New Mexico. We do have 300,000 sportsmen and –women though. It would be really nice to be able to fish the resources that our supreme court says we have a right to fish.”

The bill’s sponsor, State Senator Richard C. Martinez (D- Espanola), did not respond to requests for comment.

Experts agree that the new law is a mess, and would likely have trouble standing up to a legal challenge. After all, as Americans, we enjoy a system of checks and balances in which the judiciary exists, in part, to ensure the rule of law and to insulate an individual’s rights from the whims of politics. And the judiciary has been crystal clear on the matter.

But no one believes challenging the law would be quick, cheap, or easy. In Utah, similar struggles have passed the 5-year mark and tallied a legal tab in the deep six figures. Mounting such an effort against a well-heeled opposition in New Mexico, where the median household income is the eighth-lowest in the nation, is a daunting proposition.

Is it unconstitutional to bar New Mexican anglers from wading their rivers? Probably. The attorney general and state supreme court have said as much. Does that make a difference if John and Jane Q. Public can’t afford to prove it? Nope, not one bit. Have fishing-access opponents added that up? You bet they have. And at the moment, the calculus looks pretty solid from their perspective.

New Mexico Wildlife Federation Executive Director Garrett VeneKlasen sees the debate from a different angle.

“Passing laws to remove rights is the essence of anti-democracy,” he said. “You may or may not care about stream access. But you have to care about the precedent of the statehouse removing your rights. If we don’t stand up together, we’re going to lose our incredible heritage in a single generation.”

So which will it be: the loss of our hunting and fishing heritage or a grievance which the state’s highest court says “ never could be long borne by a free people”?

The grades are still out, but this much is clear: public-water anglers can not afford to fail this test anywhere, but especially not in one of the driest states in the West.

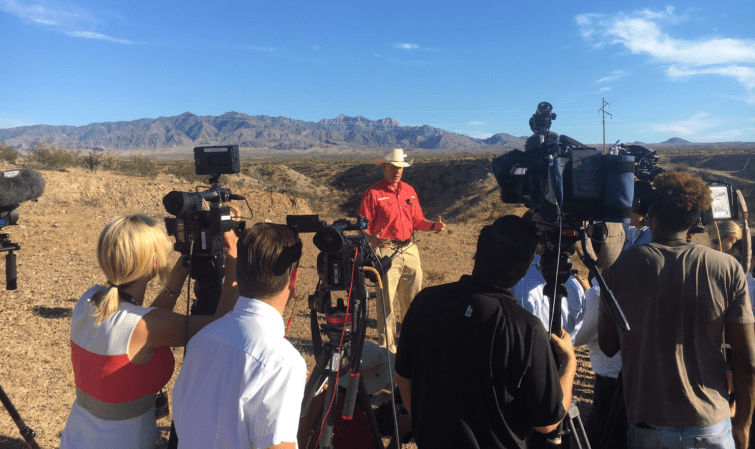

Photo by Natalie Krebs