“I know it when I see it.”

That oft-quoted line about pornography was delivered by Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart as he defined the difference between art and obscenity in the 1964 case Jacobellis v. Ohio. (Although, fun fact, his clerk is reportedly the one who helped him come to this conclusion when Stewart found himself stumped.)

In general, I consider this to be a satisfactory rule of thumb. The ends of the obscenity spectrum are pretty universally agreed upon, but the middle can get muddy. What’s tricky is that it’s 100 percent opinion based. If you’ve got sensible judgement, great (although what’s “sensible” is still wholly subjective). If you don’t, and you’re in a position of authority, then we end up with obscenity or its counterweight: censorship.

I bring this up because I’ve discovered the same principle of appropriateness applies to photography and videography of a hunt. What’s acceptable to show on camera, and what’s taboo? I feel reasonably safe in concluding that respecting a tagged or bagged animal is essential. But the question then becomes, what is respectful?

(Respectful photos are, among many other reasons, critical for ensuring anti-hunters don’t get up in arms about excessive carnage. I understand this point, so for the sake of this post, let’s keep the discussion within the hunting community. I know we don’t live in a vacuum, and photos can circulate beyond our control, but this post came about specifically due to disagreement among hunters.)

I’ve adopted this “respect it” criteria as my own standard when it comes to taking photos in the field, and even posting photos on this website. I’ve digitally corrected images in Photoshop: “washing” blood-stained shirts, “wiping” fur clean, and digitally “removing” lolling deer tongues that excited photographers neglected to tuck back inside jaws.

On the other hand, I’m an advocate of factual documentation and honest portrayals of any hunt. For instance, if you shoot an animal in the head, or the gut, or any place other than where you intended—say it. (I’m looking at you, outdoor TV.) Be honest about the shot and the recovery, even if it means admitting mistakes.

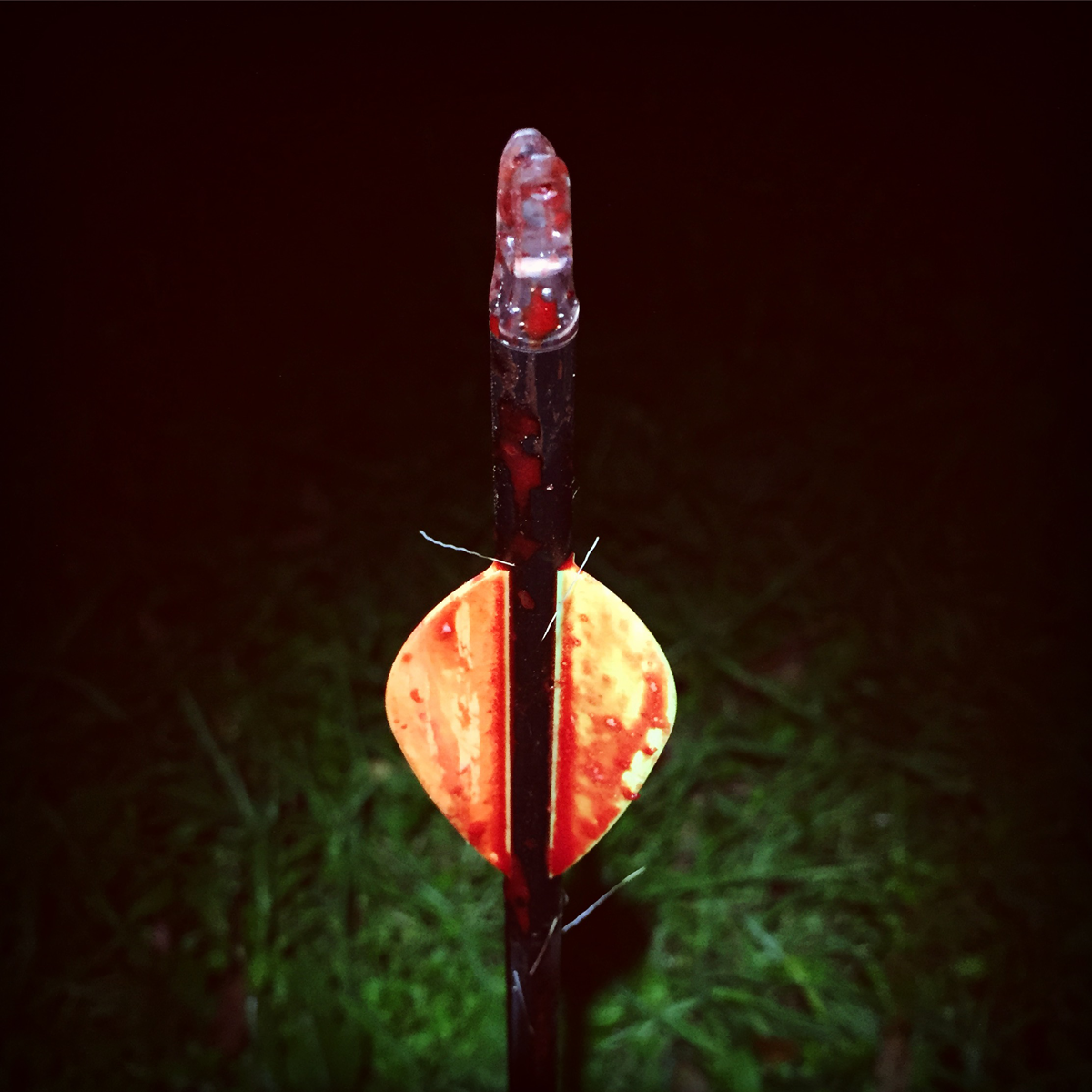

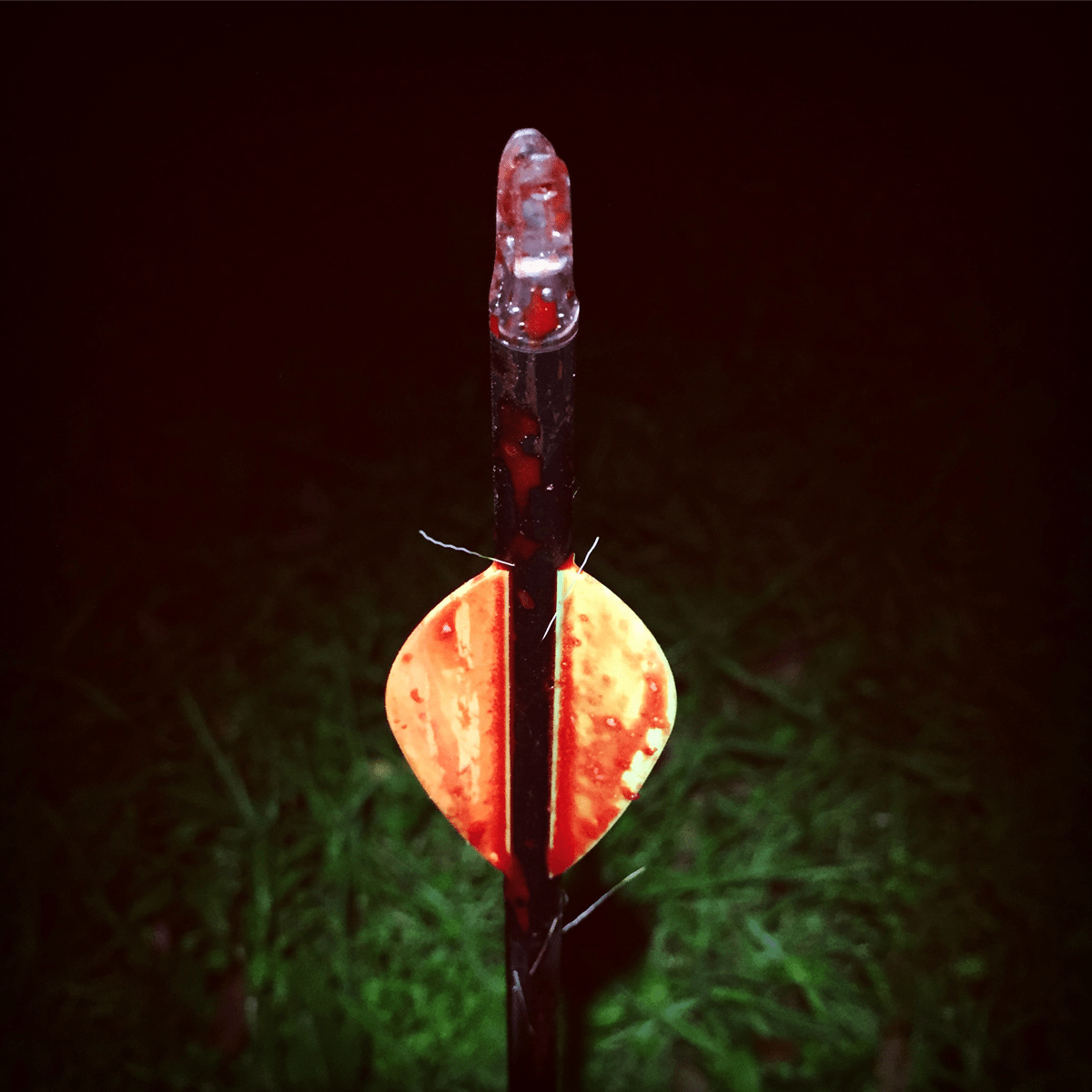

So, given all that background, consider this. The image that fueled this blog is below. Consider your reaction to it, independent of anyone else’s interpretation. Then read what I have to say for myself and let me know your thoughts.

This photo caused dissent among the OL editors. Some felt it was an accurate and necessary portrayal of a hunt. Others thought it was gratuitous gore. But when I look at it—and when I took the photo—I don’t see gore. I’d just walked up on my first bow kill, a year-and-a-half old doe that crashed seconds after a double-lung shot.

I’d killed deer before, and seen plenty of other bowkills and dead animals, from birds and squirrels to elk and bear. But this was a new scenario. This was my bloody archery deer with a large wound channel and bright, bubbly, beautiful blood spread on her smooth fur. I couldn’t help but notice the way the pattern stretched and spilled around the point of entry, and how the smaller droplets beaded perfectly on the water-repellent hide.

I’ve sat through too many modern art discussions in school, and while abstraction was never my favorite genre, this painting held appeal. This, this was abstract art if ever I’d seen it. Found art. Organic art. And I wanted to take a picture and preserve that untouched discovery, that warm, oxygenated lifeblood seeping into the cool night. This photo captured the transition of a living animal into a dead one. Soon it would become a hung carcass, ready for butchering. But for now, this was a portrait of the death of one individual deer, and one successful hunt.

Yet the photos that I sent my friends were of the bloody vanes on my arrow (a teaser) and me grinning with the dressed doe in the cluttered bed of a pickup. But the more I thought about the hunt and the more I looked at it, the more I wanted to share it. Specifically to the OL Instagram account, where we post the more artistic photos from our adventures afield with short comments and a handful of hashtags. But usually the photo speaks for itself.

Knowing it might be a bit much for some viewers, I checked with one editor before uploading it, and got an enthusiastic green light. I later got a note from another editor saying that, although the photo clearly has a lot of likes, he wasn’t okay with it.

Which got me thinking about the whole business of photographing hunts. Blood is a part of hunting, and I don’t see any use in trying to pretend it’s not. It’s not disturbing to us when recovering an animal, or heaving the guts onto the ground, or hosing out the truck bed. But take a photograph of that natural process, and it becomes an issue bordering on obscenity for many. Blood on the vanes of my arrow went unquestioned, and drops on leaves and puddles in the dirt are acceptable, too. But show the actual source of that blood? We enter a gray area; some people even see red.

So a day later, with the second editor’s comments in mind, I went back and looked at the photo. This time I saw what he saw. Just a mess of blood smeared across the screen. I should’ve kept the photo on my phone and off the internet, I thought. (Also a good rule of thumb for all you nudie enthusiasts out there.)

But then I spent several minutes studying it, and now I’m back to my original state of mind: admiration of nature and fond memories of the hunt.

I take hero shots and allow hero shots to be taken of me. It’s respectful, but it’s also artificial. Someone has removed the blood with a bottle of water or a sleeve (and maybe literally cut the tongue out of the animal). I appreciate both types of photos. But the controversial image was the moment before the tidying, and it was an important moment for me to preserve and share.

So let’s return to my question. How did you react to that photo? Let us know by leaving a comment here.