We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The tigress pads out of the sandalwood forest and into a dry stream bed with the cool purpose of an assassin. She glides in and out of the evening’s shadows, probably on her way to hunt sambar deer up the valley. I am relieved she doesn’t seem to care about me or my fellow tourists, crowded in an open-topped safari Jeep, watching her from across the wash. We are completely hushed, holding our breath for the long minute it takes her to stalk out of sight.

She is the first tiger I have ever seen in the wild, but my euphoria at the sight is subdued by the knowledge of her lethal capability. As the sun sets, I glance around for the big apex predators I cannot see, the ambushing leopards that prowl the thick brush and shadows of this national park in northern India. The park is named for hunter and naturalist Jim Corbett, who lived near here a century ago and hunted this very jungle for man-eating cats. He wrote about his adventures in a series of best-selling books. In the years following World War II, those tales transformed the modest railroad clerk of colonial India into a worldwide celebrity, and they established his reputation as one of the most famous hunters of all time. As a kid, I read Corbett’s books at night by flashlight, under the covers of my bed, imagining the growls of Bengal tigers and yellow-eyed leopards leaping out of the goatgrass.

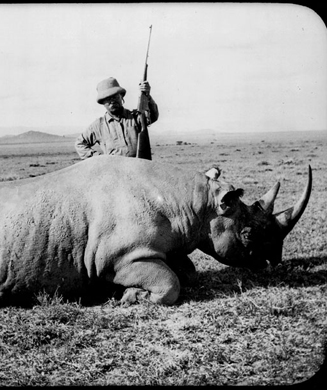

Corbett National Park is one of the last few places on earth where wild tigers roam freely. The big cats are averse to humans, but still, visitors are forbidden from getting out of vehicles, barred from bringing food into the interior of the park, and warned against making the sounds of game animals and birds. Buildings for the few concessions inside the park are ringed with electrified wire to keep the cats from coming close to humans. No one roams outside the fences at night. Corbett hunted the most dangerous cats of all—the cunning, fearless, often wounded (by porcupines, cattle hooves, or non-lethal gunshots from farmers and herders) predators that turned from hunting deer and goats to stalking humans. These predatory cats earned names associated with the places they terrorized: the Maneating Leopard of Rudraprayag, the Champawat Man-Eater, The Thak Man-Eater. The 33 cats Corbett killed over a span of 31 years were responsible for more than 1,200 human deaths.

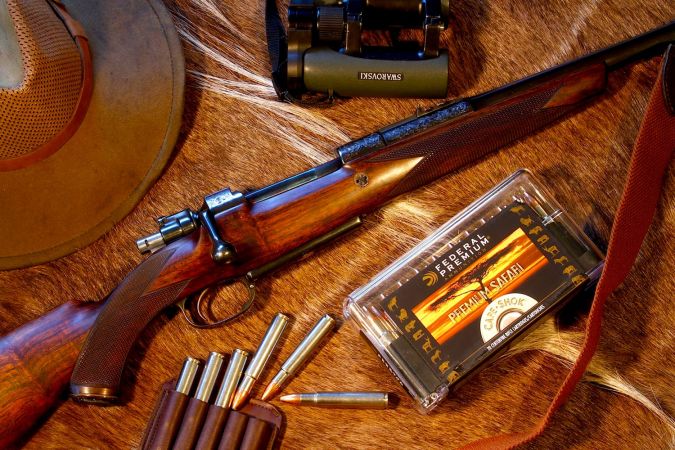

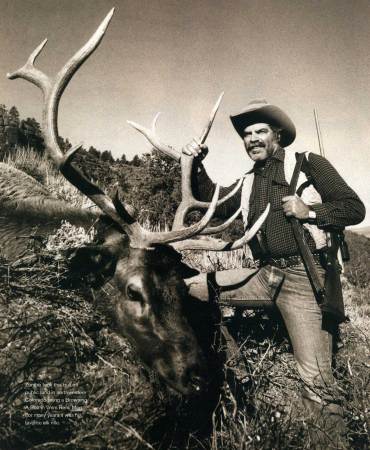

Corbett hunted alone, usually at night and often within swiping range of a lacerating claw, relying on his wits, icy nerves, and a deep understanding of wildlife behavior to pattern the predators. He also relied on a rifle, nearly always trusting his life to his favorite, a Rigby bolt-action chambered in the surprisingly light—at least for man-eaters—.275 Rigby.

LOST AND FOUND

Corbett, born and raised in the jungles of northern India, moved to Kenya just as the English colonial occupation of India was ending. He died in 1955, but not before sending his cherished Rigby to his editor at Oxford University Press in England. The rifle that had been presented to Corbett in 1907 for having killed the dreaded Man-eater of Champawat, was put in a closet at the university and forgotten.

A little more than a decade ago, it was rediscovered. But the university had a problem—Oxford was in possession of an unregistered firearm. Faced with the possibility that this piece of history might be confiscated by British authorities, university officials quietly tried to return the rifle to Rigby. Trouble was, the once mighty gunmaker had fallen on hard times and was in receivership.

Corbett’s rifle might have remained in oblivion had Marc Newton not come along. He was instrumental in the renaissance of Rigby, returning the company’s shop to London’s Vauxhall district and reviving its reputation as a maker of high-end firearms. The famous cat-killing rifle was presented to Newton a couple of years ago, and he began planning a trip that would return, for a spell, the gun to Corbett’s homeland.

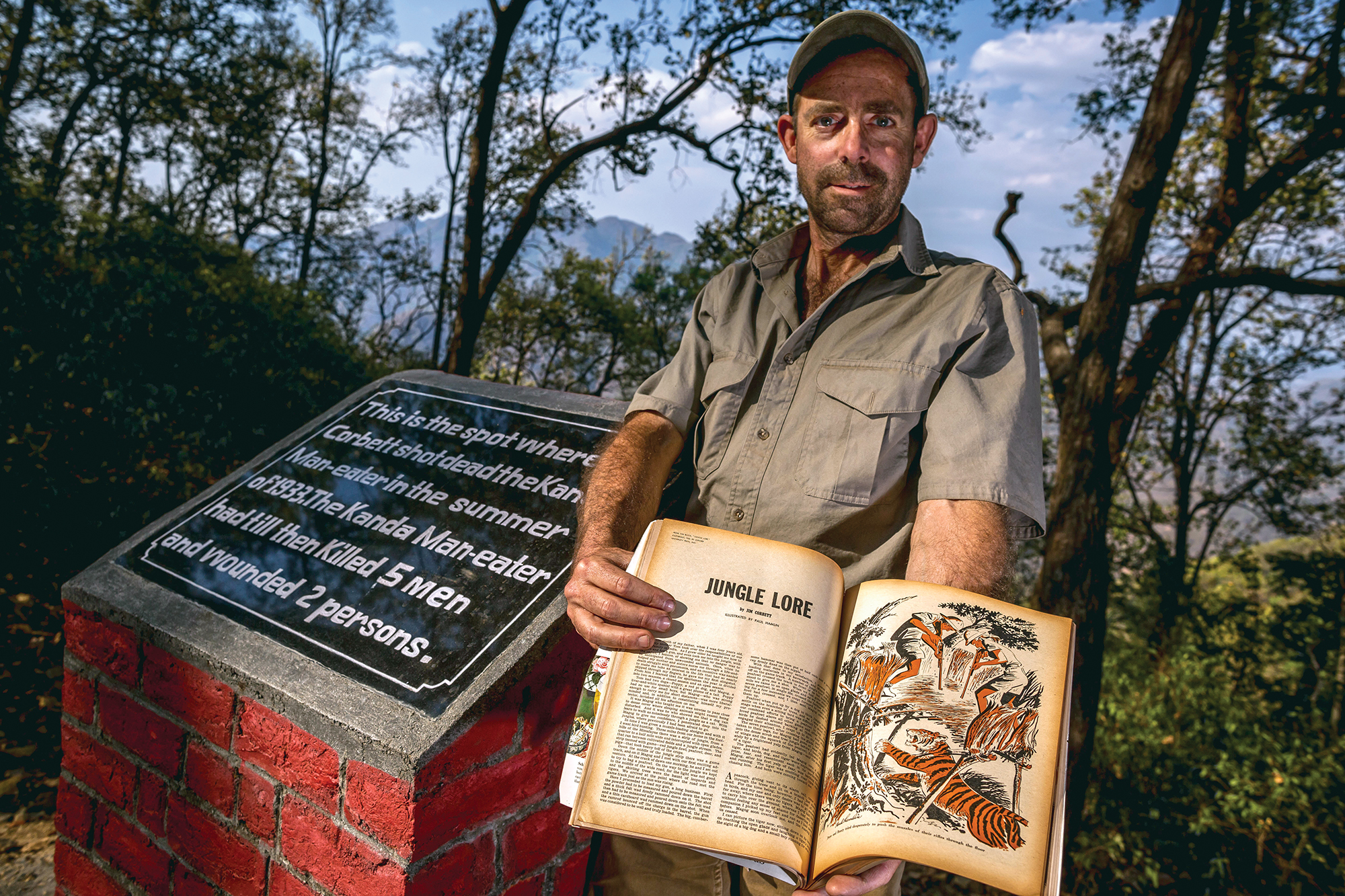

I was asked to accompany the rifle last year on its four-stop, 900-mile tour of India. A lengthy excerpt from one of Corbett’s final books, Jungle Lore, was previewed in the October 1953 issue of Outdoor Life. Because Newton intended to take the rifle to the very places where it did its grim work, he thought it fitting that I come along and read from the piece, which is considered to be Corbett’s autobiography.

This is why I found myself huddled in an open-topped Toyota in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, watching a tiger pick her way along the dry riverbed, wondering how a man could deliberately seek out these powerful, lithe predators, especially those with a demonstrated taste for the flesh of man.

LIVING HISTORY

Hunting has been banned nationwide here since the early 1970s. There is little private gun ownership in the country. So it was especially surprising to find such a large degree of affection for Jim Corbett, a celebrated hunter and confirmed gun owner. Sixty years after his death, Corbett is still revered here. When I told Happy, the man I hired outside the New Delhi airport, that I wanted him to drive me seven hours to Corbett Park to meet the rest of the Rigby party, he was ecstatic, and not only by the prospect of a full day’s wage. “Ah, Corbett-baba. Very good man,” Happy said, beaming. I learned later that the honorific “baba” is used to convey deep respect for a revered elder. I also heard Corbett described as “sadhu,” which means a holy man.

“J. Corbett = Mother Theresa with a rifle,” I wrote in my field notes.

It was gratifying to see Corbett’s life and work being celebrated, but I was uneasy about how his rifle would be received by people who had never seen a gun that wasn’t held by a soldier or a police officer. But at every stop on the Rigby tour, the gun was treated as a celebrity, almost as an extension of Corbett himself. At public rallies, people clamored to get a look at the gun. At news conferences, reporters wanted to know where the rifle had been for so long, and if it would remain in India. (No, Newton explained—the gun would return with him to anchor a Corbett exhibit in London.) Schoolchildren gawked at the hundred-year-old bolt-action, and jostled to take selfies with the rifle.

At one public event in the town of Ramnagar, headquarters for Corbett National Park, a stiff older gentleman, formally dressed in the uniform of the local military detachment, approached Newton after his public remarks. The man carried an ancient hammer-fired single-shot shotgun. It was, he told us, the regimental gun that he had used to kill more than a dozen man-eating leopards over the past 50 years in the area around the park. If we had any doubts about the gentleman’s veracity, he pulled up the leg of his trousers. The man’s shins and calves were scarred with the evidence of dreadful wounds—dealt by a leopard, he said, that wasn’t deterred by a blast from the 12-gauge. The man described reloading as the cat pulled him into the brush, pushing the muzzle of the shotgun against the leopard’s head to end the awful mauling.

As we toured the periphery of the park, we heard stories of recent marauding tigers and leopards. The big cats had surprised students walking home after dark or farmers tending livestock near the forest, and had dragged them away, leaving only a tatter of clothing hanging in a thornbush, or an unanswered cell phone ringing in a field. Corbett’s work, it seems, still isn’t done in India, where man-eaters kill on average about 30 people each year.

TERROR IN THE NIGHT

As a kid, reading his books, I was impressed by the humility of Corbett. Here was a man who had faced down certain death multiple times but had always come away with victory, represented not only by the preservation of his own life, but by the liberation of entire villages. Corbett refused to take payment for his work, and he largely shunned recognition, returning after each successful hunt to his village, where he wrote with increasing passion about the need to protect the wild places where tigers and leopards could live apart from humans. The creation of Corbett National Park in 1936 was largely a result of his advocacy. But by walking in the footsteps of Corbett, I gained a deeper appreciation for the magnitude and humanity of his work.

When a man-eater took up residence around a village, a veil of terror fell, and most outdoor activity stopped, sometimes for years. With humans too frightened to harvest it, ripening wheat was eaten by deer. Neglected livestock wandered away, children stopped attending school, cooking fires went cold with no wood to fuel them. Rural villages terrorized by a man-eater didn’t get mail, or visitors, or any outside assistance. But Corbett’s reputation after his first couple of successes in eliminating man-eaters was such that beleaguered villagers wrote petitions to the provincial government requesting his help, sending the letters by couriers brave enough to risk the killer-cat gauntlet.

In the early days of what would now joylessly be called a career as an animal-control officer, Corbett took time away from his day job—he supervised the transfer of freight from railcars to barges used to cross the wide, roilsome Ganges River—to chase cats. But after some years, he quit the railroad in order to focus on liberating villages and writing about his experiences. Corbett’s first book, Man-Eaters of Kumaon, was published in 1944.

THE RUDRAPRAYAG LEOPARD

After visiting Corbett sites around Ramnagar—we spent one day riding elephants through the jungle, where my mates and I spotted sambar and chital deer, hog deer, wild elephants, fish-eating crocodiles, and all manner of exotic birds—we followed the Hindu pilgrim route 200 miles north toward the shimmering peaks of the Himalayas. Our destination was Rudraprayag, gateway town to the sacred shrines in the snowfields along the Nepalese border.

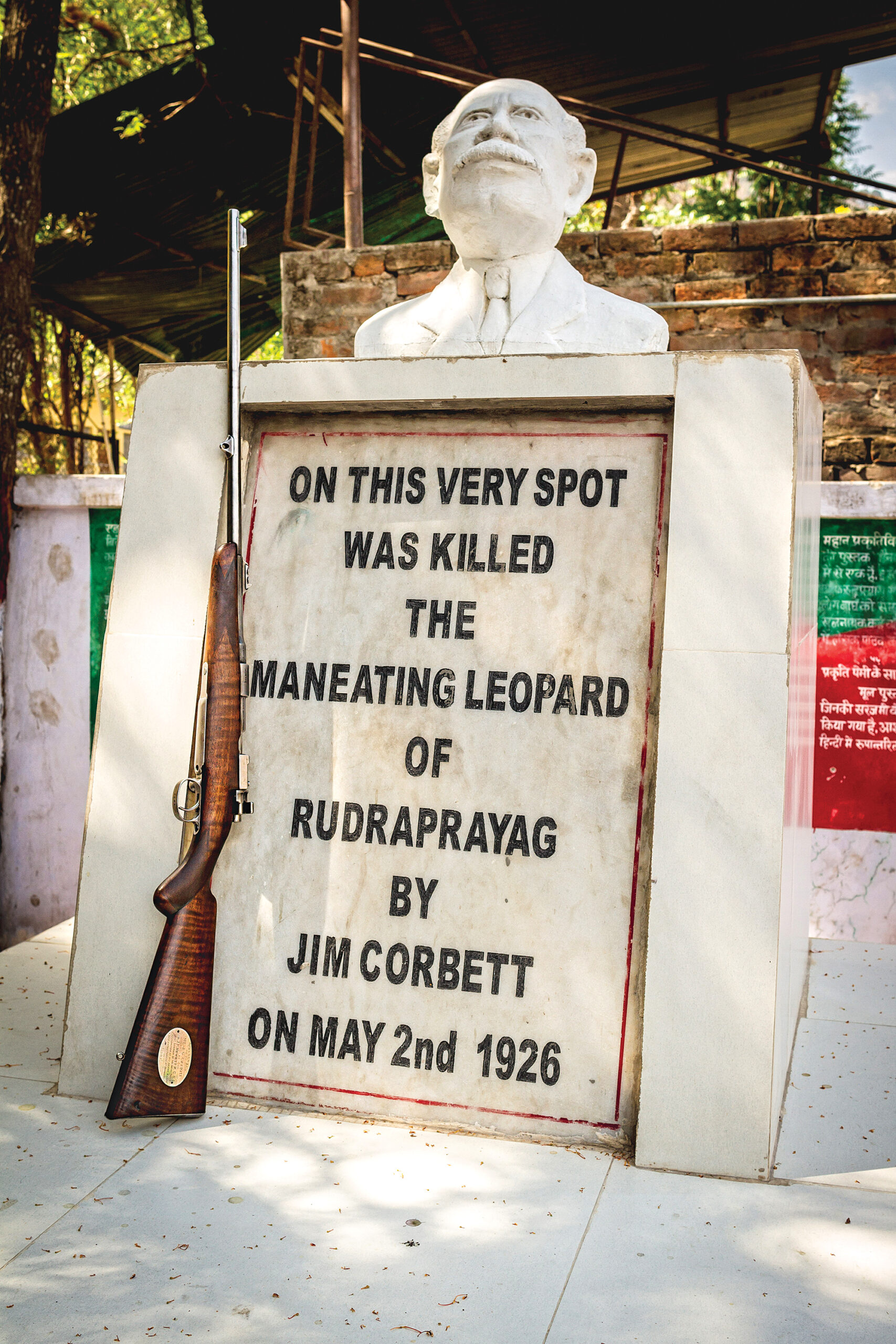

Rudraprayag, in the mountainous district of Garhwal, is perched on the steep hillsides that fall—sometimes literally, as the area is prone to earthquakes and mudslides—into the swift Ganges River. It was here, in 1926, that Corbett killed the Leopard of Rudraprayag, possibly the most infamous and homicidal of the Indian man-eaters. The leopard claimed at least 125 human victims, and likely others whose deaths were never reported or confirmed.

The leopard acquired his taste for human flesh in 1918, probably by feeding on corpses of villagers and pilgrims who died in the influenza pandemic of that year. So many people died in Rudraprayag in such short order that their bodies were thrown into the Ganges rather than being properly cremated. The leopard abandoned natural prey and, over the next eight years, terrorized the district, breaking down barricaded doors, pulling farmers through the thatch roofs of their cottages, and dragging pilgrims from their open-air sleeping platforms.

During those eight years, the busy pilgrim trail between the shrines of Kedarnath and Badrinath thinned to a trickle. No one moved at night, and camps were fortified with spears and timbered walls. Still, the killings continued.

Soldiers and trappers were called in to dispatch the serial killer, and the reward for his head grew so large that bounty hunters from across the subcontinent flocked to Rudraprayag to kill the cat.

Finally, early in 1926, Corbett was called in. He would hunt the leopard, he told officials, only if the bounty was removed and all other hunters were asked to stand down. He didn’t want his efforts to be compromised, and he didn’t want to be mistaken for the man-eater and shot by another hunter.

For 10 weeks, Corbett patterned the leopard. Finally, in May 1926, Corbett built a machan, or elevated blind, in a mango tree on the edge of town, tied a bleating goat to the base of the tree, and waited in ambush with his Rigby. Corbett killed the leopard and liberated not only the town, but also the pilgrim route across northern India.

CORBETT’S LEGACY

Our destination in Rudraprayag was a monument to Corbett built at the base of the mango tree, which is ancient and scarred but still stands on the shoulder of a highway that has become the modern pilgrims’ trail.

The local magistrate organized a rollicking festival to celebrate the gun’s return. A giant fabric tent was erected over the memorial. Schools were shut so students could attend. Shops closed for the day. The entire town crowded under the tent. Everyone wanted a glimpse of the Rigby rifle that had ended the eight-year reign of terror in this very place.

Dignitaries from across the region lined up to give speeches that were drowned out periodically by the roar of pilgrim caravans—colorful diesel trucks overloaded with people, luggage, spare tires, and fuel cans for the rough journey to the mountain shrines. From my seat at the front, I glanced up at the giant mango tree and spied a rusty wire that had become ingrown in the tree’s trunk. An elderly gentleman noticed my gaze and approached me after the festival. That is the remnant of Corbett’s machan, he told me, and added that he had grown up just outside Rudraprayag.

His father’s family had been terrorized by the leopard, and an uncle was one of the man-eater’s victims. “Without Corbett-sadhu, I think my father would not have been born,” he said. “Without my father, I would not be here. Without Corbett, I wouldn’t be here talking to you.”

As he waited to get his photo taken with Corbett’s Rigby, I wandered down to the Ganges. Everywhere the brush grew close to the river trail, I thought I heard sounds. My pace quickened, and I wished I were carrying Corbett’s Rigby in my clammy hands.