Who cast this guy anyway? Tawny complexion, a pair of skin-tight Wranglers, black 10-gallon hat, dinner-plate-sized belt buckle and boots with pointy toes. He looks like a leftover from the old “Marlboro Man” campaign. His fix isn’t burning sticks of tobacco, though. He’s into caramel and chocolate, and I mean lots of it. Maybe he’s the Mallomar Man.

Opening a wrapper and biting into his fourth candy bar of the morning, he smiles at me with chocolate-coated teeth and nods toward the horizon. “Look at all a’ them bucks,” he says, taking another chaw.

As if he had to point out the pronghorns. Across a rolling plain brushed with shadows, my eyes wander over groups of white and tan dots, some close and some in the blurry distance. It’s apparent that all of the dots are antelope. What isn’t yet clear is whether any of them is a trophy.

Peering into a spotting scope, the Mallomar Man, also known as Jim Mankin, casually begins to analyze the bucks’ merits. “Now let’s see here; he’s average…he’s a dink…he has a broken horn…he has no mass…Wait! Look right–facing us on that point. He’s a real dandy!”

We’re seated in a Jeep Wagoneer looking through door-mounted spotting scopes onto a Wyoming plain. Optics are a big part of the hunt. We’re using a Kahles 20-60X scope, although had we been afoot we would be carrying a much lighter scope (perhaps something with a 60mm objective lens and zoom eyepiece from 15-45X) or a high-powered binocular.

Staring at the tallest antelope of the bunch, I just start getting into a good daydream–a full-length feature film mostly starring me posing with the bruiser–when Mankin ambles in and drawls: “Naw, he’s not so good. Let’s go find a bigger goat.”

Mankin’s nonchalant approach is vexing, but we are getting used to it by now. Up an hour before dawn, my hunting companion, Keith Enlow of Winchester Ammunition, and I were pacing anxiously by the time Mankin finally strolled out of his trailer an hour after light and moseyed toward the central house. Stopping long enough to look us over, he chuckled and observed, “You boys’re up mighty early. Heck, ain’t no point antelope huntin’ till it’s good ‘n light. This ain’t deer huntin’, y’know.”

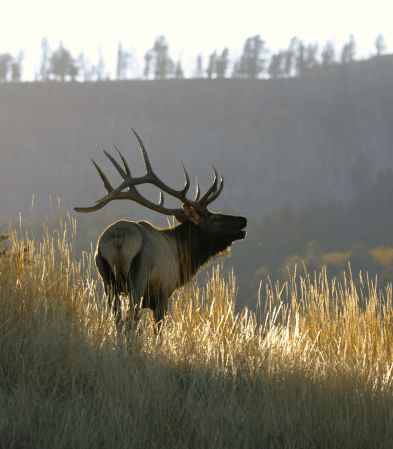

Indeed. In contrast to the excruciating climbs, saddle-sore behinds and rudimentary amenities of camp life that make, say, elk hunting so delightful, pronghorn hunting is a festive, active exercise. You spot and stalk antelope. They stand right out there under the big Western sky, scanning the horizon with their incredibly powerful eyes for predators. They’ll skedaddle at any hint of approaching danger–real or imagined. Perhaps it’s only because they are so numerous in parts of Wyoming and other Western states that hunters, on average, tag out about 80 percent of the time.

How Fast Is Fast?

“Watch this,” says Mankin, a cowboy old enough to remember the real use for horses. He slams down the gas pedal on his pickup in order to catch up to a herd of dinky pronghorns running parallel to the gravel road we’re travelling along. Then, with one casual eye on the road, he says, “See, forty-two mph? Antelope can’t run sixty. I’ve done this many times. All that stuff about them doing sixty just ain’t so.”

Justin Binfet, a biologist aide with the Wyoming Department of Game and Fish, isn’t so sure. He says it depends on who you ask. After searching his scientific manuals, he found that one source matter-of-factly states that antelope can run up to 60 mph, another says 40 mph with a “cruising speed” of 30 mph and still another claims that the animals can sprint to 55 mph.

What we do know, says Binfet, is that antelope have counter-current heat-exchange systems in their nostrils that help maintain cool body temperatures while sprinting. They also have relatively small stomachs (about half as large as those of domestic sheep) in proportion to relatively large hearts, lungs and trachea. These physiological adaptations have turned the antelope into an excellent long-distance sprinter. They seem to know the difference between racing a truck and racing a bullet. When they spot anything that looks like a hunter coming, they turn on the afterburners.

Back in the Saddle

After checking out another herd, then another, and after a blown stalk and a lot more looking, we find some “speed goats” that Mankin approves of in a group of about 100. It being the third week of the season, the antelope have already been pressured a bit. They’re now in large groups and are prone to run at the first sight of man or vehicle on the horizon.

Parked under a ridgetop, Mankin just starts to point out a good buck when Enlow interrupts him: “Back there in the mesa, there’s an even bigger buck.”

Mankin grimaces, showing a broken front tooth. “Yeah, he’s alright,” he admits. “The one in front has better hooks though.”

As Mankin looks for a route that will take us to within rifle range of the antelope, I quickly deduce that there are a couple of problems associated with hunting pronghorn. For one thing, tagging an antelope might ultimately require a long crawl through cactus and over ant-infested earth, culminating when you hear a pronghorn bark–yes, bark–and then look up to see a dust cloud with an antelope in it heading for the horizon. Plus, all antelope bucks look shockingly alike. I’m convinced this is a deceptive trait designed to confound deer hunters from east of the mighty Mississippi. Any deer hunter with a season or two under his belt can tell you at a glance if a whitetail is a shooter, but how is a hunter supposed to see a 3-inch difference between an average 12-inch antelope and a trophy 15-inch animal at 300 yards? It’s especially troubling if all you’re looking at are the 12-inch variety. [For tips, see sidebar: “Pick Your Trophy Well]

The Stalk Unfolds

In the broken high-plains desert north of Casper, Wyo., where we’re hunting, there are plenty of terrain features to use to make a stalk. In the flat, wide-open areas in some parts of the West, hunters have to get a lot more inventive to sneak up on a pronghorn. Some hunters even make cow silhouettes from sheets of plywood and attempt to “feed” their way into range.

In this case we have hay bales.

The wind is in our favor, but the antelope are nervous. Staring across the mile-long hayfield with those all-encompassing eyes, they size us up and aren’t sure whether we’re worth the bother of a quick getaway. Enlow and I roll out of the vehicle like snipers in a Hollywood action thriller while Mankin drives on as if he is innocently checking fence. The antelope fall for it.

A half-hour into our crawl we’re within 100 yards of a few small bucks, and more are coming. Here’s another thing about antelope: When you finally find the buck you want, you may have to shoot farther than any Eastern deer hunter ever thought to look. This makes range finders mandatory equipment for pronghorn hunting. Thankfully, we have one. After our crawl, we lie behind some bales, calling yardages and checking windage as if we know what we’re doing. When the bucks file closer we start to get nervous. As I said, antelope bucks all look alike.

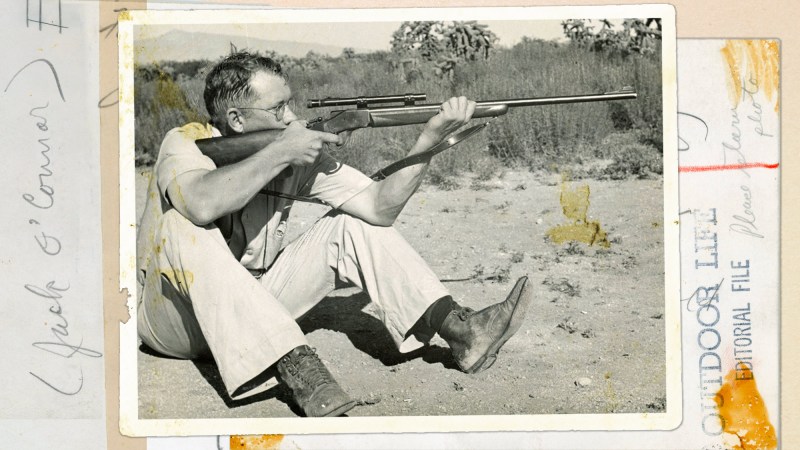

Our firearms of choice are Winchester Browning A-Bolts in 7mm Winchester Short Magnum (WSM). Because antelope are small and thin-skinned, they aren’t hard to put down. Adequate calibers include .243 Win., .25/06 Rem., .270 Win., .280 Rem. and the fairly new .270 and 7mm WSM. Sighted-in 1 inch high at 100 yards, our 7s will print 9 inches low at 300. But one has to take into account the wind here in the wide open spaces; a 10-mph crosswind (a light breeze in antelope country) will blow the particular round of 7mm WSM we’re shooting about 5 1/2 inches at 300 yards. Bipods and shooting sticks also come in handy on the plains, and a riflescope, of course, is another must. Variables of 3-9X or 4-12X are perfect. For our hunt, we’re scoped out with Kahles 3-9X42 AHs.

Choosing a Buck

The herd begins to stream past us at 100 yards; an easy shot as antelope go, but we’re flustered.

“Which buck did he say?” I ask.

“I dunno. They all look big,” says my partner.

“How about the one on the right?”

“Looks good. Shoot him.”

“Or the one in the center?”

“Yeah, he’s a dandy. Shoot him.”

Bang!

My hearing fails briefly, replaced by a high-pitched roar. My partner’s enthusiasm has gotten the better of him. He’s followed his own advice.

“Watcha’ waitin’ for?” he pleads.

A dozen bucks are staring at us, contemplating a high-gear departure. Enlow’s buck is down for keeps with a high-neck shot.

“Which one?”

“All of ’em.”

“All of ’em?”

“The one on the left. He’s a brute.”

He sure looks like one to me. Bang!

After 15 seconds of slow motion, my buck topples over.

Ten minutes later the Mallomar Man examines the fruits of our labor. He frowns. “A coupla’ twelve-inchers,” he drawls. “I guess I should have stayed with you boys. The big bucks were at the rear.”

“Big bucks?”

Despite what Mankin considers to be poor choices on our part, we can’t hide our exuberance–they all looked like trophies to us.

The Swiftest Feet These animals are considered to be among the fleetest on two or four feet. Below are their comparative speeds.

Cheetah 71 mph Pronghorn Antelope 60 mph Greyhound 45 mph Ostrich 40 mph Thoroughbred Horse 35-40 mph

Pick Your Trophy Well

Dick Mankin, a long-time Boone and Crockett scorer, observes five guidelines in judging the size of an antelope buck at a distance:

1. Judge by the prong length, not the overall length. If the prong is over 4 inches long, the antelope is a trophy.

2. Look for horns curved into a heart shape. Younger pronghorns often have straighter horns.

3. Look at the color of the tips. If they’re silver-or ivory-colored, the animal is likely mature.

4. Compare the animal to others in the herd. A true trophy has 16-inch horns with 7-inch bases.

5. Look at the horns’ overall mass. Like teenagers, antelope horns grow up before they grow out. If the bases are thick, chances are it’s a keeper.