We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The old “possibles” bag sure ain’t what it used to be. Back when I first started burning black powder, the process of loading a muzzleloading rifle was about as complicated as mixing up a batch of hoehandle cornbread and seemed to take nearly as long. This was especially true if you figured in the time spent melting lead, casting bullets, cutting sprues and prowling about fabric shops in search of cotton cloth of the right weave and thickness to make tight patches for best accuracy with round, lead bullets.

Nowadays these gentle joys have pretty much gone the way of bustles and high-button shoes. The three innovations that have most changed the way we load, shoot and hunt with muzzleloading firearms–aside from the now nearly ubiquitous in-line ignition rifle–are sabot-encased bullets, one-piece pelletized propellants and shotshell primers. Predictably, each of these rankle tradition-minded purists, but to hunters who view the special blackpowder seasons only as a few more days of hunting, they have been little less than a godsend.

The trappings that delight traditionalists–such as bullet casting, arguing about the merits of using spit vs. tallow to lube patches and pouring precise measures of propellant charges from a flask or powder horn–are only bothersome impediments to hunters concerned with getting on with their hunting in the quickest and simplest way. This is why the saboted bullet is rapidly becoming the projectile of choice among non-traditional muzzleloader hunters.

The convenience of Hodgdon’s pelletized Pyrodex is self-evident. Instead of measuring loose propellant into a muzzleloader’s muzzle, you simply drop in one or more pellets, depending on the caliber, bullet weight and velocity you want. Tedious measuring is eliminated. Of course, you should read the instructions first to have a clear understanding of what you’re doing.

PRIMER PROS AND CONS

The use of modern shotshell primers, rather than traditional percussion caps, falls into the “why-didn’t-someone-think-of-this-sooner” category. In addition to having a more intense flame and surer ignition, they are manufactured to exacting tolerances that tend to ensure better shot-to-shot ignition uniformity, which, of course, is a handmaiden of good accuracy.

The downside of shotgun primers is that whereas fired percussion caps are easily removed from the nipple–usually by a quick flick of your fingernail–shotshell primers tend to expand tightly into the pocket recess and often require a sharp-edged tool to pry them out. This can slow the reloading process, unless you use a handy tool such as that offered by Traditions Performance Firearms, which has a stiff pry blade on one end and a primer holder on the other. Hopefully, future muzzleloading rifles designed for shotshell primers will incorporate automatic primer extraction, as does the “E-Z Tip” extractor on Thompson/Center’s Encore ML barrel.

Shotgun primers are not interchangeable with percussion caps, but some in-line rifles with percussion-cap ignition can be converted to shotshell priming by changing the breech plug. If you already have an in-line, you might want to check this out. Remington, for one, offers a three-way conversion that lets you use shotshell primers, Number 11- or musket-size caps.

From the standpoint of accuracy and downrange performance on game, the main focus in muzzleloading circles of late has been on sabots. In case this is new to you, a sabot (taken from the French word for shoe–and perhaps best known for the act of rebellious French workers who caused work stoppages by tossing their wooden sabots into industrial machinery, thereby committing sabotage, which provides a clue to the correct pronunciation of “sabot”) wholly or partially encases a bullet, protecting it from the rigors of actual contact with the rifling while providing a tight gas seal. Upon exiting the muzzle, the sabot separates, leaving the bullet to fly free. Saboted bullets are nothing new, having long been used in military ordnance.

THE SABOT REVOLUTION

Saboted bullets are a natural for muzzleloaders because they simplify and expedite the loading process. Best of all, good-quality copper-jacketed hunting bullets can be united with a sabot, thus putting penetration and expansion on a par–or very nearly so–with that of centerfire rifle bullets.

But progress, especially a radical innovation such as the saboted conical bullets for muzzleloaders, brings with it new problems. When saboted bullets first appeared they were mostly considered an experimental novelty, even by their makers. Accordingly, the first on the market were thin-jacketed pistol bullets encased in plastic sabots. Predictably, penetration and expansion were sometimes erratic because the bullets had actually been designed for the lower velocities of handguns, not the higher impact speeds of rifles generating muzzle velocities upward of 2,000 feet per second.

This was a short-term problem, however. Makers of premium bullets caught on to the growing trend and designed bullets specifically for muzzleloaders. Nowadays blackpowder hunters have their pick of such premium bullets as the Barnes solid copper hollow-pointed MZ, Nosler’s Partition and other good rounds.

ENHANCING ACCURACY

A more lasting problem, however, has been unsatisfactory accuracy with saboted bullets. One of the most common problems is simply loading the wrong bullet in the wrong rifle. By and large, the muzzleloading rifles marketed a short generation ago were meant to shoot patched, round, lead bullets. Accordingly, the rate of rifling twist was rather slow (one turn in 60 inches or even slower is common), since round bullets don’t require a lot of spin to fly true. By comparison, your favorite centerfire .270 or .30/06 has a twist of 1 in 10 inches.

The slower rifling of older blackpowder rifles gets to be a problem with longer conical bullets, which need a faster spin to stabilize for best accuracy. This is why many modern muzzleloading rifles have a twist rate of 1 in 28 inches or thereabouts.

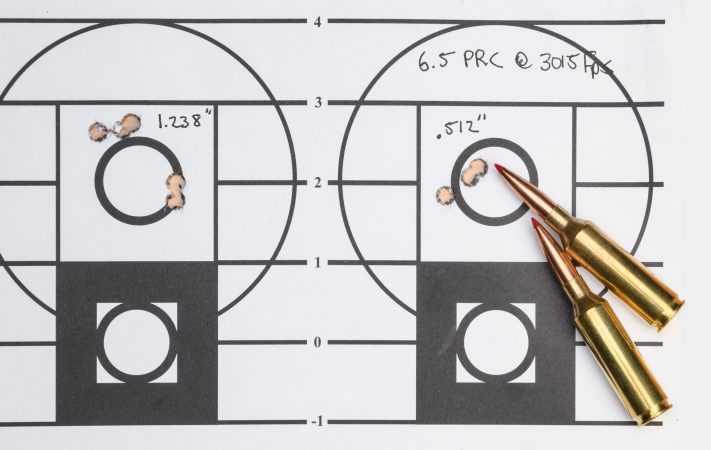

When the bullet is matched to the barrel and properly loaded, the accuracy of saboted bullets can challenge that of a good centerfire hunting rifle. When OUTDOOR LIFE did a landmark evaluation of muzzleloading rifle performance a few years back [June 1996], we found some saboted bullets capable of achieving the Holy Grail of accuracy–three shots inside an inch at 100 yards.

FOUL PLAY

Another problem presented by sabot-encased bullets is “plastic scrub” fouling. Traces of plastic stuck tight in the bore build up into hard-to-remove, accuracy-spoiling deposits. Shotgunners discovered this nuisance when plastic shot cups appeared and have long since learned that a stiff brush and elbow grease is the most effective way to get it out.

Plastic scrub fouling is even more of a problem for blackpowder hunters, because the plastic accumulation of only a few shots welds itself tightly to the bore and measurably degrades accuracy. Worse yet, the solvents typically used to remove the fouling of black powder have little effect on plastic fouling. So the best way to get it out is with a stiff copper brush of the correct size and a powerful solvent such as that used to remove smokeless powder and copper fouling from centerfire rifles.

GO NATURAL

Pursuers of best accuracy from their muzzleloaders tell me that they clean after every shot when accuracy testing with saboted bullets. Also, manufacturers advise cleaning between shots when customers complain about bad accuracy. Obviously a hunter can’t stop to clean his rifle when he needs to make a quick follow-up shot. A natural lubricant can reduce the plastic scrub problem.

The reason for using natural rather than petroleum-based lubricants is because natural lubes are mainly water-soluble and dissolve when the barrel is cleaned with water or the usual muzzleloading cleaning solvents. Petroleum-type lubes, however, resist water, so what you might end up with is a mess of water-resistant fouling.

CHECK THE BARREL

Recently I checked the actual bore diameter of a few supposedly .50-caliber rifles and found variations of a few thousandths of an inch smaller or larger than true .500 inches. This doesn’t necessarily mean that any of those barrels will be less accurate or develop less velocity than a “true” barrel, but it does point out the need to match the size of your saboted bullet to your barrel.

Accuracy tests with undersized sabots and/or oversized bores have demonstrated, time and again, that a loose fit sometimes leads to miserable performance, even when bullet and barrel are of otherwise top quality. So if you’ve been getting poor accuracy from your rifle with sabots, try another, somewhat larger size. Like barrels, sabots vary somewhat in size and can be checked with a micrometer.

The flared, obturating “skirt” on sabots may also give you a false sense of a tight fit. What you really want is a close fit against the tops of the lands for the full length of the sabot. With a bit of practice you’ll be able to feel when a sabot fits right when you push it home with the ramrod. Another way to check is by inspecting sabots after firing. The rifling imprints should be even around the sides. If they are uneven or indicate a cocked, uneven position against the lands, you need to change bullets or improve your loading technique.

TIP

SWITCH PRIMERS Fitting shotgun-type primers is facilitated using this dog-bone tool. If you are plagued with excessively tight shotshell primers, switch brands. There are slight differences in dimensions from brand to brand and the way they expand.

TIP

GET THE RIFLING RIGHT Sabot-encased bullets, pelletized propellants and shotgun-style primers are three innovations that have greatly enhanced the accuracy of modern blackpowder rifles. If you’re planning to buy a muzzleloader for hunting and intend to use conical saboted bullets, be sure the rifling is compatible.

TIP

BUTTER THE BORE After loading the rifle, but before priming, lightly lubricate the bore with a natural-type lubricant such as lanolin or T/C’s Bore Butter. This will reduce the tendency of plastic to adhere to the bore.

TIP

CHECK BEFORE YOU BUY Before you buy a new muzzleloader, go to the store with a handful of machinists’ plug gauges so you can determine the true bore diameter and thus match the bullet or sabot-encased bullet with the correct bore size for best accuracy.

TIP

KNOW THE REGS Before buying one of the latest-style muzzleloaders, be sure to check your state’s hunting regulations. The laws concerning blackpowder hunting are complex and confusing in some states; certain types of rifles and ignition systems might be prohibited.

TIP

MATCH YOUR ROD When you’re ramming conical bullets down the bore, you can hold them in truer alignment by using a ramrod tip contoured to match the shape of the bullet’s point.