We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

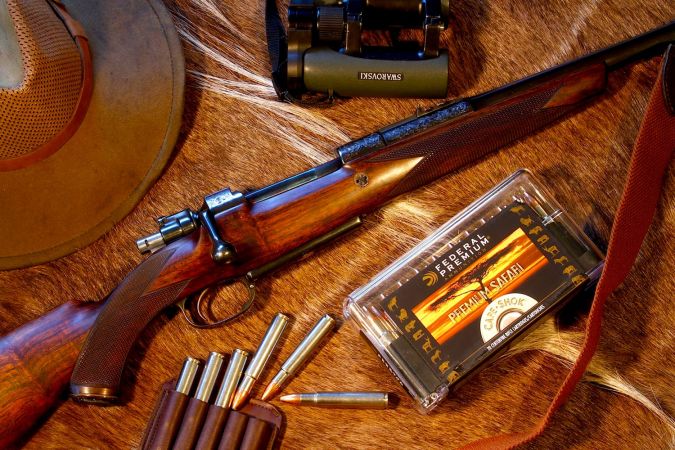

“Stopping rifle” is a term widely used to describe a rifle/cartridge/bullet combination supposedly big, strong, and deadly enough to protect humans from death and destruction at the claws, fangs, horns, and physical pummeling from myriad large beasts, most especially those of African lineage.

An advantage with bolt-action stopping rifles is the ability to easily adjust them to put all bullets to the same point of aim.

Rifles built on the Mauser Controlled Round Feed action gradually won over traditionalists used to the side-by-side double rifle.

The .30-06 on far left gives perspective to the big bores chambered in stopping rifles.

The .458 Lott was created by stretching the .458 Win. Mag. back to the original case length of the .375 H&H and sticking to the 45-caliber bullet size. It adds a bit more speed and power to the .458, endearing it to many dangerous game hunters interested in maximum “stopping power.”

A controlled round feed action like this Kimber in .458 Win. Mag. has become quite popular with African PHs. While not the ultimate stopping rifle, it is realtively light, affordable, and quick for 4 or 5 shots.

A belt load of .470 Nitro Express rounds is only as useful as the speed with which a shooter can load them in a double rifle.

The .470 Nitro Express was created for double rifles, its rim ensuring plenty of surface area for the extractor to grab.

Big stoping rounds like the 470 NE in the breech of a double rifle look more like shotshells than rifle cartridges.

The .577 Nitro Express is one of the largest stopping rifles, bested only by the rare 600 NE and rarer 700 NE, neither of which is commonly used.

A look down the muzzles of a double rifle explains the meaning of “big bore.”

This Mauser bolt removed from the rifle action shows how its claw extractor holds cartridges like this .416 Rigby against the bolt face for straight-line push into chamber.

The only difference between a big bore dangerous game rifle and stopping rifle is the moment at which it is fired. Many sporting rifles work well as stopping rifles, but hard core guides can’t often afford higher grade guns like this Heym double.

Hiking through elephant country often reveals tracks that suggest your stopping rifle might be undersized.

Any stopping rifle’s power is enhanced by the addition of several more, usually carried by clients and assistant guides.

Practice and more practice can make the CRF bolt-action nearly as fast as any side-by-side for two shots and much faster for 4 or 5.

Even a starter double with intercepting sears and articulated triggers like these Heym M88s costs many times what a base model CRF bolt action costs.

The CRF Mauser perfected in 1898 slowly began showing up in the hands of professional dangerous game hunters in Africa because it was durable, reliable, and provided 4 or 5 shots instead of just 2.

Plain or fancy, the double trigger double barrel remains a popular option as a stopping rifle.

Engraved dangerous game heads do not a stopping rifle make, but they suggest the possibilities.

The Mauser CRF action in a properly fitted stock can prove more effective for multiple shots than the best double rifle.

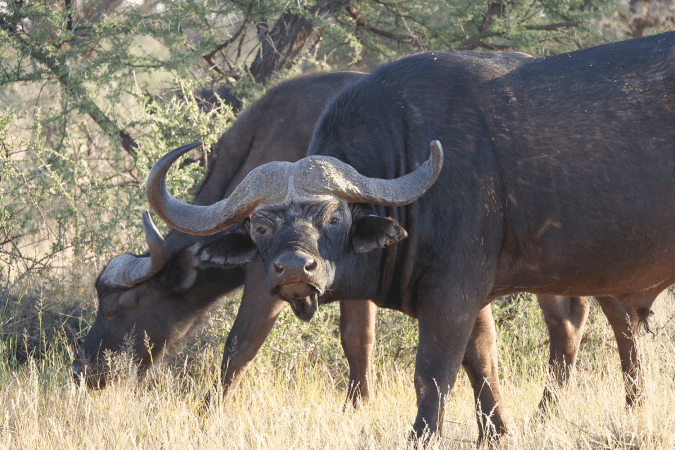

We’ve all heard the stories. Hunter shoots Cape buffalo through the chest with a .416 Remington Magnum. Buffalo charges. Uh oh!

Staring black death in the face, the hunter pumps two more 400-grain bullets into it. His Professional Hunter (PH) slams it with two 525-grain bullets from a .505 Gibbs, each bullet carrying 6,200 foot-pounds of kinetic energy. Despite absorbing 27,000 ft.-lbs. of kinetic energy from 5 ounces of lead and copper, the 1,600-pound buffalo keeps coming, flicks the hunter into an arcing, 20-foot, three-and-a-half twist, double summersault. Then he bulldozes the PH to the ground, and grinds him into the dust.

Stopping rifle? More than a handful of PHs have died while trusting what I call the ” stopping rifle myth.” Maybe it’s time we adopted a more accurate description.

“Stopping rifle” is a term widely used to describe a rifle/cartridge/bullet combination supposedly big, strong, and deadly enough to protect humans from death and destruction at the claws, fangs, horns, and physical pummeling from a myriad of large beasts, most especially those of African dangerous game.

Think lion, leopard, buffalo, rhino, hippo, elephant. From North America throw in polar, brown, and grizzly bears. Let India contribute tigers and more leopards. I think we can agree these are all large, tough, and mean enough to reduce the largest, strongest human to a bittersweet memory.

Lest you question the frequency of large animal attacks, understand that hippos alone send 500 to as many as 2,000 humans(estimated) to their final rest each year. Crocs are credited with 1,000 annually, elephants 100, lions 100, buffalo 200. These are 21st century numbers compiled by a menagerie of beasts drastically reduced from the common abundance of earlier centuries when death by wild animals was not uncommon.

The two man-eating Tsavo lions, for example, killed 135 people and stopped construction of a national railroad. A cold-blooded killer known as Gustave the crocodile in Burundi snapped out the lives of more than 300 people. A salt-water croc in Burma topped this by taking out anywhere from 400 to 980 humans.

Read Next: The Guns You Wish You Had

Leopards, while infamous man-eaters in India, rarely kill in Africa. Nevertheless, they rather frequently shred and rearrange human anatomies. The Rudraprayag leopard in India removed 125 humans from the earthly realm. The Leopard of Panar took out some 400. It’s distant and much larger cousin, the Champawat tiger, tallied 436.

Rampaging elephants haven’t been christened with names, probably because they don’t eat folks. They just squash them, sometimes impaling them on their massive tusks for dramatic emphasis.

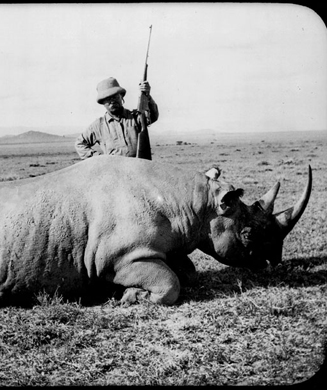

Rhinos are no longer much of a threat simply because we’ve allowed them to be poached to the brink of extinction, but throughout the early years of African settlement, they were notorious for running through rather than around those who disturbed them. Take it from those who can no longer tell you themselves: a rhino horn through your torso ain’t fun.

First of the Stoppers

Stopping the rapid approach of such animals hell bent on intimate contact is what drove the evolution of the dangerous game or stopping rifle. The first of these were side-by-side doubles that sprang from the big bore 8-gauge and 4-gauge muzzleloading shotguns first hired to take the biggest game in Africa. Beginning in the 1890s, breech-loaded brass cartridges burning high-energy smokeless powder were propelling tough, deep-penetrating jacketed bullets capable of punching through the biggest game. Terminal performance improved dramatically. But hunters clung to the old-fashioned side-by-side doubles because they were balanced, durable, and redundant. A second barrel with its own trigger and striker was reliably dependable. And it provided the fastest second shot in the business. Still does.

Nonetheless, the controlled round feed (CRF) bolt-action Mauser repeater gradually weaseled its way into the dangerous game battery. While not quite as fast for two shots, the Mauser and Mauser-inspired CRF bolt-actions of other makes offered the fastest third and fourth shots in the business. Still do.

Lever-actions, pumps, and auto-loaders never quite made the grade. Arguably they don’t have the strength and/or reliability of the double and CRF bolt. So today, more than 120 years after the Big Two dangerous game rifles made their marks, they remain the gold standards for “stopping rifles” if they are chambered for the right cartridges.

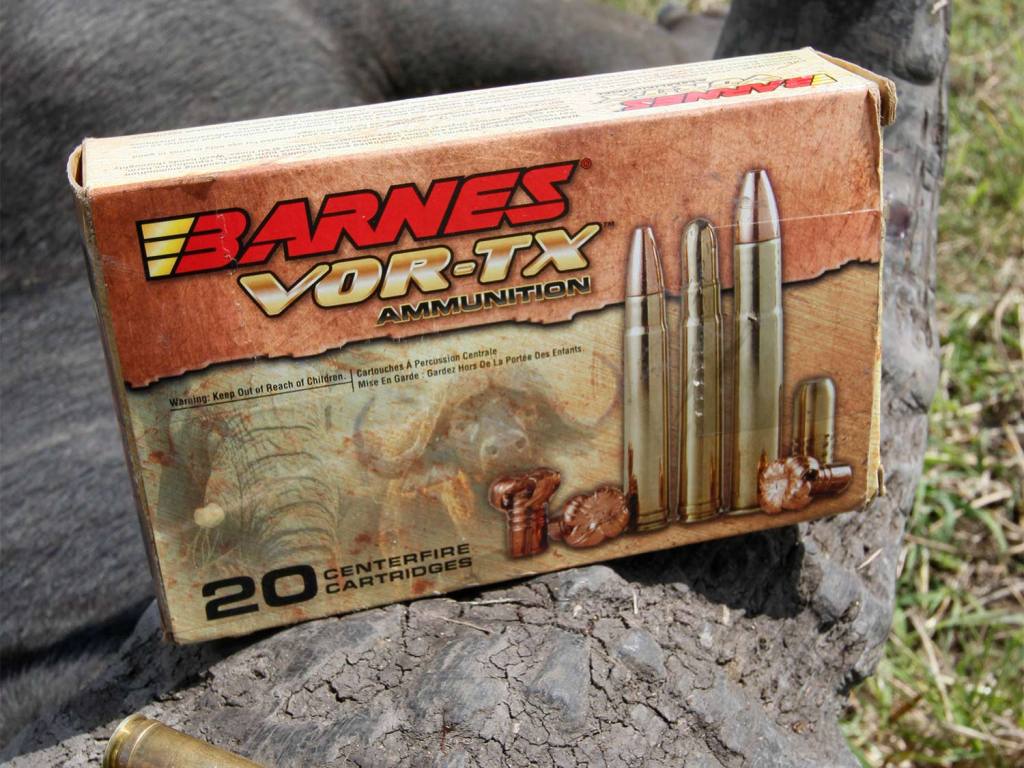

The classic double rifles are chambered for long, fat, rimmed cartridges that drive bullets spanning .416 to .577 inches in diameter. The magazine rifles usually handle rimless rounds of similar size. Rimmed cartridges extract and eject most reliably in double rifles. Rimless rounds function most reliably in bolt-action rifles.

As for stopping power, the 400- to 525-grain bullets thrown by these rifles usually leave the muzzle at 2,000- to 2,400 fps carrying 4,000 to 6,000 ft.-lbs. of kinetic energy. One ft.-lb. of kinetic energy is theoretically enough to lift 1 pound of mass a foot off the ground. So 5,000 ft.-lbs. of striking energy from a 500-grain bullet should be capable of at least moving a 1,500-pound standing buffalo three to four feet backward, no?

No.

The Knock on Knockdown Power

So-called knockdown power in bullets doesn’t work that way the numbers suggest. The brutal truth is that stopping rifles really aren’t. Unless those massive bullets are delivered directly into or near enough to a large anima’s central nervous system to short circuit the electricity, Black Death is going to keep on coming.

You can slice and dice and analyze this via any number of “systems” from Taylor’s Knock Out to the Optimal Game Weight formula to the beloved Momentum theory of bullet performance. It won’t matter. Dangerous game animals subscribe to none of them. And they’ve proven this many times over, select specimens absorbing ounces of lead and tons of energy without ending their deadly attacks.

Read Next: The Ultimate Truck Gun Build

Now it is true that many animals have been turned by these big bullets parked close to the “lights out” central nervous system. Elephants and lions in particular are claimed to be dissuaded by “close but no cigar” hits. The solid thump apparently inspires them to turn from the attack. But we don’t label these “turning rifles.”

So why do we call them stopping rifles? “Slowing rifle” might be more accurate. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying I want to wade into the elephant grass after a wounded buffalo with a .308 Winchester in hand. But I’ve read and heard too many sordid tales of “stopping rifles” that should have but didn’t to fully trust them, either.

Truth be told, a relatively light, tough, solid bullet going 2,000 fps or faster can stop the largest, most dangerous, most adrenaline-fueled beast IF said bullet strikes brain or spinal column. The iconic W.D.M. “Karamojo” Bell most convincingly proved this by flooring hundreds and hundreds of elephants and buffalo with 173-grain solids from a .275 Rigby (7x57mm Mauser.) It is argued and argued effectively that Bell was possessed of exceptional composure and exceptional field accuracy. But it can also be argued that others can aspire to and train to this level. And a light recoiling rifle can more easily be mastered for precision shot placement and faster, precisely aimed follow up shots than can a brutally recoiling rifle so since our classic “stopping rifles” have proven less than reliable, should we try lighter options?

Or should we just stick with the classics, but start calling them “slowing rifles?”