Are we truly that desperate with sage grouse? We need to raise them like chickens?

The Wyoming Game and Fish Commission this week approved rules that would greatly expand the ability for licensed bird breeders to capture sage grouse eggs and rear them in hatcheries. As a lifetime fan of the big grey bombers, this struck me as sad news.

So I asked gonzo bird hunter and wildlife biologist Ed Arnett, of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, for his read on the topic.

“Captive breeding is an option of very last resort,” Arnett said. “We are not anywhere near that desperate when it comes to sage grouse.”

Sage grouse are the largest of North America’s grouse species, native to the basin-and-range country of the interior West. Sage grouse are declining sharply to the point of being proposed to be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Where local populations are healthy, the birds are hunted in a sustainable manner that poses no threat to the bird’s existence. However, they do face serious threats on multiple fronts: invasive weeds like cheat grass, diseases like West Nile, and habitat destruction as oil and gas development puts the bulldozer blade to the sagebrush-steppe habitat the birds require.

Most sage grouse depend on public lands, such as those managed by the Bureau of Land Management. Those lands are also open for oil and gas development. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke wants America to uncork its energy resources to make America, in his words “energy dominant.” Conservationists wonder where the room is for wildlife in that vision.

Supporters of Wyoming’s captive rearing experiment say that intensive rearing is one more tool in the box for sage grouse recovery. And for those who don’t know better, it might seem logical. After all, we pen-raise ringneck pheasants by the thousand.

“A sage grouse is not a ringneck pheasant,” said Arnett. “They are just totally different, biologically, behaviorally.”

Sage grouse have a sensitive and complex courtship ritual that is fine-tuned to the arid, vast landscapes they require. Efforts to restore populations of other locally extirpated prairie grouse populations, such as sharptail grouse and prairie chickens, have proven largely fruitless.

The bottom line is habitat. If we cannot conserve the West’s sagelands, we will lose the bird.

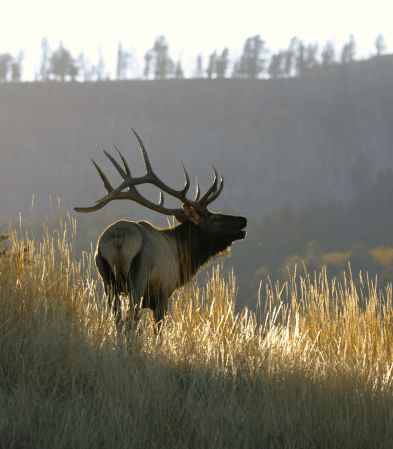

And that’s the point, Arnett said. It’s not about hatching eggs. It’s about the land. The sagebrush-steppe ecosystem supports not only sage grouse, but also mule deer, pronghorn, elk, and a host of other native species. What’s good for the bird is good for the herd.

Perhaps hatcheries have a place, but we cannot take our eyes off the ball. Habitat is what matters.