We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Patrick Babcock, owner of Cree River Lodge, has seen a lot of exotic fishing lures come through his remote northern Saskatchewan pike camp, where sow-bellied fish weighing up to 30 pounds are caught every year. Giant swimbaits. Clacking spinnerbaits. Topwater plugs of all designs, sizes, and actions. In-line spinners. All manner of diving crankbaits. And flies with more Mylar, sparkle, and glitz than a Junior Miss pageant. But he knows that for giant Canada northern pike, the simplest fishing lure can be the most effective.

When I visited Cree River last summer, I fell into the same big-lure-for-big-fish swoon, and cast (with a degree of difficulty) a 1-pound plastic duck imitation that burbled and spit as its eager yellow feet churned on the retrieve. Babcock told me to put away that contraption, which he labeled my “super-silly sputter cluck” (its real name is the Suicide Duck), and handed me a lure so quintessentially Canadian that I thought he was putting me on.

It was a red-and-white spoon, exactly like the classic Dardevle. Painted in the middle of its convex side, however, was a maple leaf instead of a picture of a jaunty devil with horns. I promptly caught a 36-inch pike on that spoon—the $3.99 price tag from Canadian Tire still stuck to its cupped side.

As he released my northern, Babcock told me the most consistent lure for trophy pike—which he considers a fish of more than 45 inches—is a simple spoon.

“Guys pull out their $15 crankbaits and their big spinners, and I’ll let them fish with them—for a day,” he says.

“Then I’ll hand them a five-of-diamonds, and they’ll not only catch more fish on it, but they’ll generally catch bigger fish on it.”

The five-of-diamonds is a mustard-yellow spoon with crimson diamonds—that’s right, five of them—on the convex face; the concave side is finished in a burnished gold. Babcock is also bullish on the classic red-and-white Dardevle spoon, and its Canadian Tire knockoff.

“The real sleeper up here is the crackle-back frog pattern,” says Babcock, whose home water is sprawling Wapata Lake in the roadless bush south of Stoney Rapids. He shows me a 3-inch spoon with a blotchy green-and-black pattern.

“I call it ‘The Pickle,’ he says. “Don’t know why it produces—probably because our water can be off-green for much of the summer—but it’s a great spoon.”

Indeed, it is. I caught a dozen girthy pike on The Pickle before I abandoned it for a spoon from my own collection that I hoped might match the success that my friend and fishing buddy Nathan Borowski was having on my brass-and-red-eye Eppinger Wiggler.

Trophy-Fish Dream Trip

Borowski and I had talked for a couple of years about coming to Wapata Lake. He knows I love big, surly pike, and Nathan, who works press relations for Cabela’s, was eager to field test a line of new rods, reels, and dry bags. Borowski played the classic neophyte line: “Just bring the lures you think will work, and I’ll borrow your tackle,” he told me when we met up in Saskatoon. Here he was, in the front of the boat, outfishing me with my own spoon.

Watching him yard in one trophy pike after another—while failing to suppress his annoying whoops and giggles—gave me a tutorial on why spoons are so effective here. These six primary takeaways can easily be applied to almost any other location or species.

Spoons cover a lot of water. They typically cast far and accurately, and one of the most underappreciated elements of fishing success is the amount of time that your hook is in the water.

Spoons occupy the right water. Fished properly, they run neither too deep nor too shallow. In Saskatchewan, where pike often move into bays in the summer to soak up 20 hours of sunlight a day, if you are clipping the tops of submerged weed beds with your lure, you are in the strike zone. It’s easy to regulate the depth of a spoon’s dive by speeding or slowing its retrieve, and Borowski was doing a masterly job of varying the running depth by changing up his reeling intensity, pausing his retrieve, and twitching his rod tip to impart more action to his lure.

Spoons are forgiving. You don’t have to know how to twitch them just so or how to calculate their dive rate. You just reel, and the spoon supplies the erratic action, even on the end of a heavy steel leader. This is the magic of the classic spoon’s bent-metal design—it flutters to one side, then stabilizes briefly before flitting in the other direction, the front part tracking with the line but the aft end woggling around the way a wounded minnow might founder. For predatory fish like northern pike, that action is the appeal; the color of the spoon serves only to catch their attention.

Spoons are versatile. You can cast them into shallow rocks and speed-retrieve them so they don’t get snagged. You can cast into deep bays, wait for them to sink to the bottom, and then pop the rod tip to give them a jigging action. You can troll them. Or you can tip their hooks with cut bait or even a jig skirt or rubber worm to coax light bites.

Spoons are easy on fish. For Babcock, an advocate of catch-and-release, spoons increase fish survival rates.

“Crankbaits have two sets of trebles—sometimes three—and those big pike roll and fight so much that normally all the hooks end up in the fish. That’s a lot of holes, plus all those hooks get hung up in my net. A single barbless treble is all you really need.”Spoons are hardy. Big pike can tear apart a balsa wood hard bait and denude the rubber skirt of a spinnerbait. But spoons tend to hold up well to the shredding violence that big pike dish out. Babcock swears that a spoon that’s scarred and scratched and runs just a little bit out of whack is a better fish-catcher than one fresh from the blister pack.

Endless Variation

After I accepted that Wapata Lake was going to be a spoon bite, I started keeping track of which pattern provided the most action. Nathan’s red-eyed Wiggler was a top producer, but the classic red-and-white Dardevle was close behind, and a no-name green-and-black spoon I brought—Babcock called it “The Dull Pickle”—caught nearly as many 40-inch pike as any of the others.

Interestingly, the more vivacious patterns—fire-tiger, fluorescent orange, and chartreuse—didn’t catch as many fish as the classic finishes of hammered nickel, hammered brass, and pearlescent.

Big fish like big meals, right? When it comes to spoons, that’s not always the case. Borowski and I caught our biggest fish of the trip—44- and 45-inch pike—on 2 ½-inch models, solidly in the middle of the size spectrum for metallic spoons. Despite their heft, larger spoons are harder to cast far, and their wide surface area often has them wallowing on the surface rather than running a few feet deep, where larger fish like to hang out. And narrower weight-forward spoons, like Krocodiles and Kastmasters, tend to run too deep.

Wall of Fame

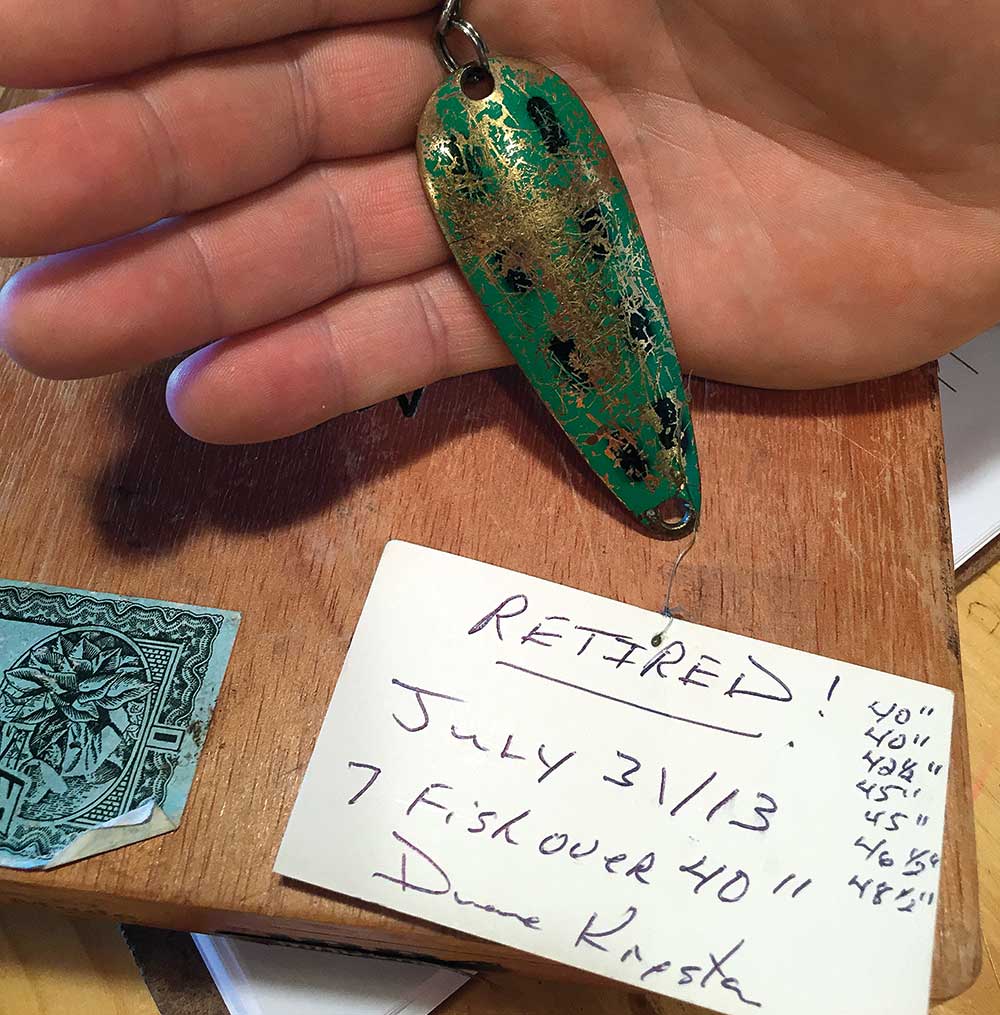

On the timbered wall of Cree River Lodge, behind the roughhewn pine counter where pike anglers can buy a wide variety of tackle (at inflated backcountry prices), a number of battered and scarred spoons hang by their mangled treble hooks. These are the retired all-stars of Wapata Lake, mutilated spoons that have caught numbers of 40-plus-inch pike.

Babcock pulls down one specimen, a Pickle spoon so scratched and chipped that bare metal gleams through the paint job. An index card accompanies the spoon like an interpretive sign at a museum.

“Retired!” screams the card. “July 31, 2013. Seven fish over 40–40, 40, 42 ½, 45, 45, 46 ½, 48 ½.”

“That was a day!” Babcock gushes. “And that was a helluva spoon.” He tests the sharpness of the hooks. “I bet it would still yard up a pike or two.”