Ask your hunting or fishing buddies about the craziest things they’ve found in the woods and waters, and get ready for some dandy stories. I did just that a few years ago, quizzing a friend who grew up along Montana’s Yellowstone River about favorite finds in a lifetime afield. One year, when the river was especially low, he was fishing a rocky riffle that had been used as a ford by the Crow and Cheyenne for centuries, and later by buffalo hunters. Something in the shallow water caught his eye. He waded out and pulled up an old rifle. It was a rust-encrusted Winchester, the lever open as though its original owner had been in the process of jacking a shell into the chamber when the gun was lost.

“I’ve always wondered about that,” my friend mused. “Was it a trapper ambushed by Indians? Was it a hunter making a follow-up shot? Did the rifle slip out of a hand? Or was the shooter killed in action?”

We’ll never know. A discovery like that raises more questions than it answers, which is precisely the thrum of a good find.

I asked a number of buddies about their most curious finds. A few also told me of memorable losses. Here are their stories. —Andrew McKean

1. Buck Redux —Chad Schearer

When I was 10, I received a Buck Model 102 knife for Christmas. My father had my name and hometown engraved on the blade, and I carried that knife everywhere. One day my brother borrowed it for a bowhunt in the Little Belt Mountains, and he lost it. A couple of years later, it was returned via the U.S. Postal Service. Another public-land hunter had found my knife, discovered my name, and took the time to return it. Sportsmen are some of the finest people to walk this earth.

2. The Rusty Pan —Gary Guidice

Back in the early ’80s, my brother and I got the idea that we wanted to float an Alaskan river that had never seen a raft. We heard about a remote creek that was running unseasonably high and talked an outfitter with a floatplane into dropping us at its headwaters. It would be a 14-day float to the take-out spot.

Halfway into the trip, we rounded a bend and there was an entire log cabin beached on a brushy sandbar. It must have been washed down from its original location in the spring runoff. After a week of seeing no signs of humans, we had to stop. We rummaged the place, feeling like trespassers even though it hadn’t been inhabited in decades. We found broken jars, tools, old cans, and even a rusted-out gold pan. We left that cabin just as we found it, still feeling like intruders. We knew the next high water would finish the task and return those hewn timbers to the river. My brother and I still talk about that find, and wonder about the old trapper and prospector who built the shack and lived way out there. And I still wish I’d kept his rusty old gold pan.

3. The Original Hunter —Bill Hanlon

I was Dall sheep hunting with two buddies in the most beautiful real estate I’ve ever seen, the massive Tatshenshini-Alsek wilderness of northern British Columbia. We had backpacked in 55 kilometers to the head of a series of glaciers and spotted a band of rams on a distant ridge. As we were picking our way along the lower edge of a glacier, I found a stick, then another. This is rock-and-ice country, so it was unusual to see wood. Then I realized I was looking at an artifact—maybe an atlatl.

Just then one of my buddies said, “I think I found the poor fellow who lost that stuff.” It was a partial body, 30 feet above us. All we could see was a pelvis. The legs were still frozen in the glacier.

We photographed the find, and then went and killed a couple of beautiful rams. We reported our discovery when we got back to civilization, and it became a major anthropological event, the oldest organically preserved human remains in North America, estimated at 500 years old. The First Nations called him Kwäday Dän Ts’ìnchi, which translates to Long Ago Person Found.

We later learned the body was that of a Tlingit hunter 20 years old and in perfect physical condition when he died. With him, he had a robe made of arctic ground squirrel skins and sinew from mountain goat and blue whale, plus a smoked sockeye salmon in a pocket and a hat woven from spruce root.

The news made a splash, but despite extensive searching, archaeologists weren’t able to find the man’s head. Four years later, my buddies and I drew sheep tags again for the area, and we went back to the glacier, which had receded a good deal since our original visit. And not 100 yards from where we found the pelvis, we found the head.

How was it that we made both these finds? A lot of people have talked about the astronomical odds, but I don’t think it was coincidence. It’s taken me years to reach this conclusion, but I think we were meant to find him. He was a hunter, and it took a hunter to find a hunter. I hope if something like what happened to him—falling in a crevasse or getting lost in a midsummer storm and dying of hypothermia—happens to me, it’s another hunter who finds me 500 years later.

4. Cutbank Bounty —Dallas Capdeville

I was driving my boat down the Milk River in Montana when I spotted the base of an antler sticking out of a bank that had been caving off for several years. I started digging and pulled out a 6-point elk shed.

5. The Jade Boulder —A.G. Russell

My story should be called “Found, Then Lost.”

In the California deer season, back in the late ‘50s, Fred Hoy and I were hunting blacktails in the Salmon-Trinity Alps. In three seasons, we never heard a shot that was not fired by one of our own party. We would always go in as far as the fire-control roads would allow, then hike a few miles up to a cirque lake near the mountaintop, where we’d catch trout for breakfast every morning. The first day of the season, I shot a buck, and we had to run downhill for several hundred yards before killing him. While resting prior to dressing out and packing the meat and hide back to camp, Fred inspected a greenish boulder on the hillside.

A rockhound, Fred pronounced that the boulder was one of two forms of jade. We tried chipping off a piece, even shooting a piece off, without success. It was a large boulder, nearly 5 feet in diameter and more or less round.

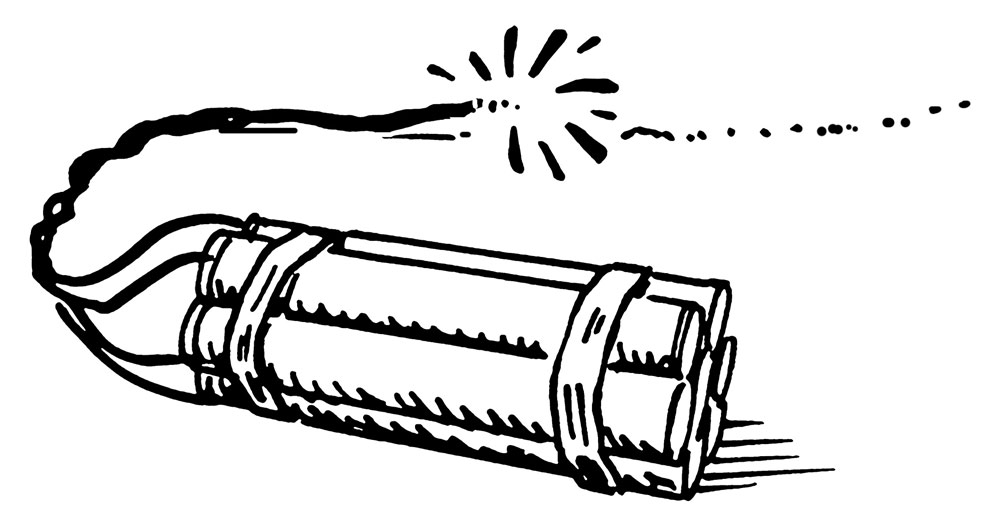

We went back the next season with a four-wheel-drive truck, a winch, ropes, pulleys, and even prima cord—Fred was an explosives expert, too. We were determined to remove that jade boulder. We spent five days looking for that rock but never found it again.

6. Looking For Fish —Rachel Vandevoort

“The fish win today.” That’s what my Gramps said when we neglected to throw our rods in the truck for a drive to the fishing hole two hours from home. And that’s what he’d say when we would get skunked on one of our many fishing trips to the lake.

He called it looking for fish, and to tell the truth, Gramps did most of the looking while I looked forward to the catching. Miles, hours, days we looked for fish at that lake. Thermoses of sugary coffee, yellow bags of Lays potato chips, Wonder bread and bologna sandwiches fueled our fishing trips. We’d look for fish when it was so cold the eyelets froze up after every third strip of line, and when it was so windy that we could barely cast. There were days when we’d drive right up to the lake and sit in the cab of the truck, hoping for a break in the weather so we could look for fish.

“The fish win today,” Gramps would say when he surrendered to the weather and turned for home.

I used to think we spent all those days just looking for fish, but years later, I know that what I really found on those trips was time with Gramps. And that’s something that I can never find again.

7. The Magic Lure —Ryan Kirby

I was 9 years old and completely obsessed with fishing. I fished morning, noon, and night over the summers on our Illinois farm, insisting even on fishing in my Little League uniform after games.

A friend had a VHS tape of a seminar given by Babe Winkelman, fishing with a large orange-bellied crankbait. Up until then, I had stuck to spoons, spinnerbaits, and rubber worms, but I just knew this crankbait was my ticket to the Bassmaster tour. I had to have it, even though I was fishing on quarter-acre farm ponds and Babe was running the thing 15 feet deep on giant open-water lakes. I bought one of the lures from a mail-order catalog and couldn’t wait to try it on our south pond. It was so heavy I could cast it all the way over the pond to the far shore.

The first evening I tied that lure on, my dad left me to fish alone while he rode the three-wheeler over the hill to check on soybeans. A few minutes after he left, I had a massive hit from a giant bass. I finally got him to shore. I was so little I had to lean way backward, doubling over my Zebco. I was just about to swing the bass out of the water when he broke the line, plopped down in 2 inches of water, and started flopping around in the muddy cattle tracks.

I threw down my pole and went for him, but each time I reached for his mouth, he thrashed and threw that crankbait’s giant treble hook toward my hand. Eventually the fish got into enough water to gain some leverage, and with one giant slap of his tail he swam away like a torpedo, crankbait and all. As that orange beacon in the side of his mouth disappeared in the muddy water, I cried.

When my dad returned to find me at the edge of the pond, I told him the story. He didn’t believe me, of course, but as a sort of father’s consolation, he told me that we’d just have to try and catch that fish again someday. I was heartbroken. Not only did I lose the best fish of my life up until then, but I had lost my prized crankbait.

A week later, my dad was hunting for mushrooms in the woods below the pond when he saw something colorful in the brush. It was my crankbait. Apparently, raccoons had nabbed the fish, which had probably died from exertion after our fight. The coons carried the fish over the dam, ate it, and left my crankbait behind after determining it was inedible.

I never caught another fish on that lure. I never made the Bassmaster tour. But I’ll never forget that fish or the orange-bellied crankbait that did it in.

8. Hey! Hook! —Keith Balfourd

While still-hunting for whitetails along the Niobrara River outside Valentine, Neb., I came across a split tree. In the split was an old hay hook, the kind with a wooden T-handle made for handling bales of hay or straw. A long time ago, the tool had evidently been stuck in the fork of the tree, and it died and split. The hook was easy to pull out. It appeared to be hand-forged and pounded out of a large carriage bolt. There was no sign of any old homestead or even a hay field, for that matter. Mother Nature had taken back whatever living the owners were trying to carve out of that place on the frontier.

9. Wreckage in the Raggeds —Aaron Oelger

Back in 2013, I was bowhunting for elk in The Raggeds, a wilderness area west of Crested Butte, Colo., when I happened on a large sheet of twisted and bent metal high on the slopes of a timbered mountain. I later learned that it was the remains of a single-engine aircraft that had crashed in the area some 20 years earlier. Most of the wreckage had been dismantled and removed by packtrains, but the mules were unable to carry the engine. Later, I went back to the area and located the engine. My guide recalled that the plane was owned by the Colorado Department of National Resources. I never learned if there had been loss of life in the wreck, but it was sure a spooky thing to find an abandoned aircraft engine sitting in the middle of the wilderness.

10. The Ancients —Jared Frasier

Last year, I tagged along with a friend on his Montana mountain goat hunt. I wanted to set up above him—all the better to spot and film from—and as I was looking for a hide, I found a little rock fort, maybe 10,000 feet up on a ridge. Whoever made the fort had wedged little sheets of crystal-covered rock in the gaps of the larger rocks they had stacked, presumably to keep wind and weather out. As I made myself comfortable in the hide, I looked down and found the ground covered in obsidian flakes, presumably left there by the same hunters who had made the fort.

11. Angling for Evidence —Mitch Butler

Long after a man was convicted of a high-profile murder in the affluent town of Greenwood Village, Colo., I found the murder weapon. I was only about 7 years old, but I was a consummate golf-course angler and crayfish collector. I was exploring Little Dry Creek, probably looking for golf balls I could sell back to the pro shop, when I saw a square bit of metal sticking out of the muddy bank under a bridge. I excavated a bit, determined the metal was the bottom of a magazine, and came up with the .45 Auto that had been used in the homicide and then apparently tossed off the bridge. The authorities had combed the area for days following the murder, but it took a 7-year-old sportsman to produce the evidence.

12. Ewe Tunes —Dirk Monson

Several years ago, while bowhunting elk in eastern Montana, I was sitting on a sandstone point glassing the valley below when I looked down in the sand and saw what I thought was a sardine can buried in the grit. Since I always pick up trash I encounter when I am hunting, I began to dig the can out of the sand so I could pack it back to my camp and dispose of it properly.

After exposing enough of the can to pull it out of the ground, I realized it was not a can at all, but rather a harmonica. It was clearly very old and had been buried out there for a long time. The outer shell was in near-perfect condition, but the brass and wooden “guts” were a little worse for wear. I could see remnants of the thin strips of wood that formed the channels the air flowed through to guide it over the brass reeds to create the sound. I put the harmonica in my pack and took it back to camp to clean it up. Upon seeing its vintage, and how long it must have been buried, I developed a theory about how it got there and who might have lost it.

The harmonica is a Clover No. 130. It has patent dates stamped in its metal: Sept. 27, 1892, and June 7, 1898. I’m guessing it was made around the turn of the 20th century. The area I was hunting was homesteaded by a local family who raised sheep and later cattle on the land. My hunch is that the harmonica belonged to one of the men hired to herd the sheep. The valley below the point still holds the remains of a sandstone corral. I can imagine a sheep herder sitting on the sandstone point one evening just as I had done. But instead of looking for elk, he was using the vantage to keep an eye on the sheep he was tasked with tending. What did he do to pass the time? I’m guessing he played the harmonica—until he lost it.

13. Perfect Point —Chris Hrenko

While hunting rabbits and squirrels, I found a large obsidian arrowhead, completely intact, along the edge of a cornfield behind my grandparents’ house in Ohio. It was almost as big as today’s iPhone, and its edges were sharpened at parallel angles. I always wondered if it was designed to spin in flight. It’s hard to imagine what people must have gone through to get that obsidian hundreds of miles back to Ohio in the days before roads and bridges. The nearest source for obsidian back in the pre-settlement era was probably the Yellowstone Plateau. I wondered about the person who must have treasured it, and how they lost it.

I brought the point to school to show my sixth-grade class. Our school had been built by a contractor that specialized in prison construction, and it was one of those modern buildings with exposed duct work and floors of stained concrete. Some bozo classmate of mine dropped the arrowhead onto that hard floor, and it shattered into pieces.

14. Recovery —Brenda Valentine

Some 40 years ago, my brother and I got into a world of trouble when we lost the two post-hole diggers that we had used to help my father fence a part of our farm. The tools were never found by either my father or my brother in their lifetimes. But during a turkey hunt, I found the missing diggers. They had rotted handles and rusted metal, but they are now safely stored in my shed.

15. Little Cleo —Marc Kloker

I found a lure buried in the dirt bank of a local fishing pond when I was in high school. It was a Little Cleo WIGL spoon with the picture of a topless young lady (Miss Cleo?) stamped into its metal surface. I thought it was the coolest thing ever, especially as I was a teenager with a teenager’s libido.

I have kept it in my various tackle boxes ever since, never once using it, for more than 20 years. I would call it a good-luck charm, but because I never use it, I can’t say if it brings me good or bad luck.

Once I discovered the internet, I also learned more about the origin of Little Cleo. Apparently, she was a real-life performer in the 1930s in New York City. The developer of the lure was “inspired” by Cleo and stamped the likeness of the topless belly dancer on the back side of the spoon.

It may not be a fish magnet, but it’s a treasure in my lure collection.

Read Next: Lucky Charms: Our Favorite Odds-Tippers and the Stories Behind Them

16. Huck Finn’s Rod —Gary Garth

I spotted a thumb-sized stick poking from the sand near the downstream bank of a long, teardrop-shaped Mississippi River sandbar, the river’s dangerous current licking at my bare feet. My mother would have been wild with worry had she known I was there. Only it wasn’t a stick. It was a rod handle, the rotting cork turned black by the river water. I clawed into the hot sand.

Attached was an old reel, a levelwind of some sort. Heavy. Solid. Simple. The handle was missing but a knot of line remained, stubbornly attached like hair clinging to a decaying corpse. A smidgen of rod, made maybe of wood, jutted ahead of the reel.

This was long before everyone carried a camera in their pocket, so the only picture I have of it is the one in my head. I held the old tool in my hands, turning it over, wiping and blowing away the sand, feeling Huckleberry Finn–ish in a late summer hangover sort of way. Do I regret having left the old remnant on the sand? Sometimes. But it connected me to the river in a way nothing else had. It still does.

17. Fire to the Bear Gods —Ben Long

It was late summer, and the irrigation reservoir along the west front of the Rockies was drawn low. I walked the caked mudflats, along with anthropologist Barney Reeves, looking for small circles of rocks, evidence of ancient cooking fires. These campfires had burned centuries before a dam inundated this valley, and the low water was making them visible. We found blackened bones of bison and bighorns, the preferred prey over deer and elk. Only once in his career, Reeves told me, had he found a black bear femur in one of these pits.

One fire pit stood out. Instead of common stones, every rock in the ring was red argillite. It was a ceremonial fire ring, Reeves said. Perhaps the pit had been at the center of a sweat lodge. But what shocked me was what was inside the ring of red rocks. The pit was full of the canines—the fang teeth—of adult grizzly bears. The bones had crumbled with time, but the harder, enamel-coated teeth remained easily identifiable. Someone long ago, for some long-forgotten reason, had cooked the skulls of several grizzlies in that spot.

I imagined the scene: glowing coals, smell of burnt flesh and sweetgrass, prayers to an ancient god offered in an ancient tongue. I snapped a picture and we left the site untouched. The next spring’s snowmelt refilled the reservoir, taking the mystery with it.