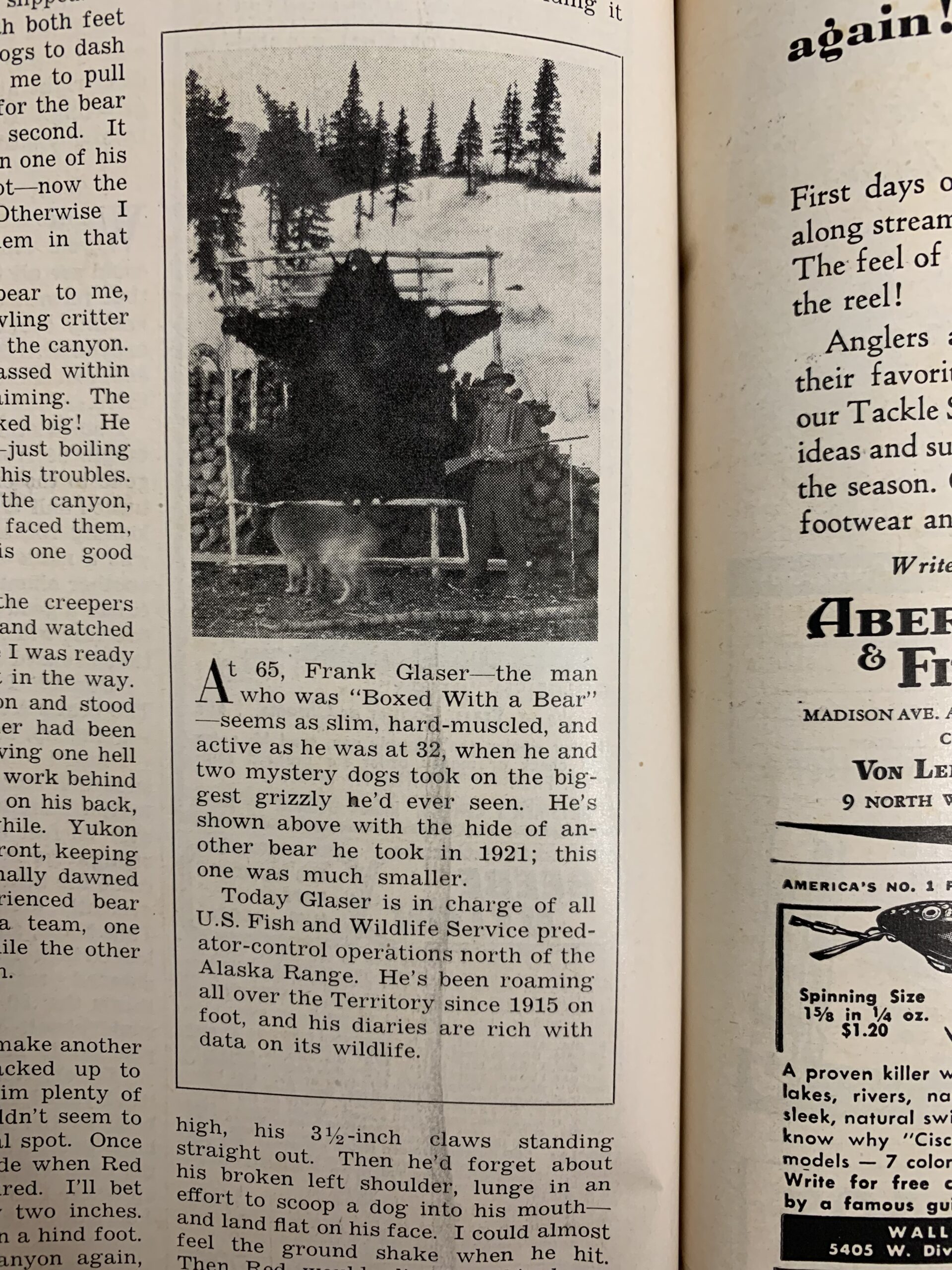

This story from the Outdoor Life archives, by Frank Glaser, was told to—and written by—Jim Rearden. It first appeared in the April 1954 issue of Outdoor Life and was retold in Rearden’s book Alaska’s Wolf Man, a collection of Glaser’s adventures in Alaska in the first half of the 20th century. Countless adventures and stories from Alaska have forever been lost to time, but this is one, luckily, is preserved. It’s one of my favorite Frank Glaser stories, and someday I’m going to find that box canyon. When I do, I’ll sit quietly, trying to hear the echoes of the past. —Tyler Freel

Boxed With a Bear

By Frank Glaser, as told to Jim Rearden

IN VICTORIA LAND, north of Coronation Gulf—as well as in other parts of the Canadian arctic—sled dogs are as important to an Eskimo as a horse is to a cowhand. They’re strictly work dogs, not pets, and are used mainly to pull sleds. Not so well known is their ability to fight polar bears. When a Victoria Land Eskimo sees Nanook he looses his dogs and they pile into the unlucky bear, keeping him occupied until the Eskimo can move close enough to get in a chest shot from his rifle as the bear rears up on its hind legs. Many dogs are killed by the bears, but those that survive become expert at bear baiting.

In 1918 a tow-haired prospector named Elmer “stampeded” from Valdez, Alaska, to Fort Norman in the District of Mackenzie, west of Great Bear Lake, where an oil strike had been made. He spent the summer, fall, and winter there before he became discouraged and decided to return to his placer diggings near Valdez. A number of Eskimos were freighting for the stampeders, using their teams of powerful, wolf-like dogs. Among the latter were several teams from Victoria Land, more than 400 miles to the northeast.

Elmer bought one of these teams and started homeward. He’d never handled such fine dogs and was amazed at their power and endurance. They were far bigger than the 50 and 60-pound huskies of Alaska, and when he arrived at Valdez after a lengthy trip he was in love with them. Nothing in the world could have persuaded him to part with the magnificent animals.

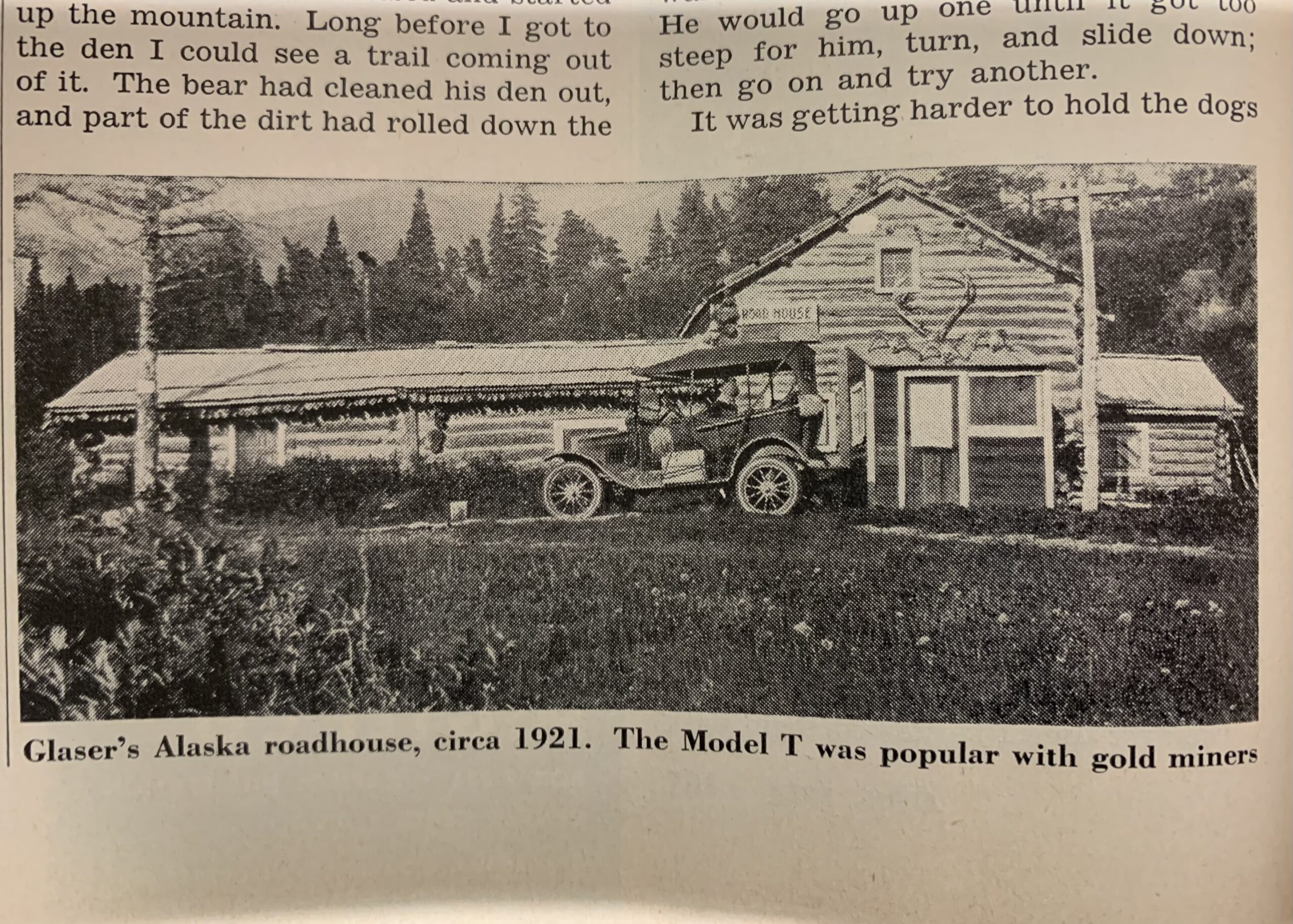

On a day in August, 1921, I sat on an Alaska mountainside training my binoculars on the biggest grizzly bear I’d ever seen. At that time I owned and operated the Black Rapids Roadhouse on the old Valdez trail. I also market-hunted for the Alaska road commission, getting two bits a pound for mountain sheep, caribou, and moose. I probably would have done it for two cents a pound, I enjoyed hunting so much.

Road crews under Col. Wilds P. Richardson were working on the old trail, turning it into the Richardson Highway that today corkscrews through windy Isabella Pass in the Alaska Range. I kept them well supplied with meat, mostly mountain mutton. Winters I trapped fox, lynx, and an occasional wolverine.

That August day I kept my glasses on the black grizzly, which I had seen several times during the summer across the Delta River from the roadhouse. Every time I’d spotted him I’d got excited. Little, cream-colored Toklat-type grizzlies were fairly common in that country—in fact the region was known for its bears. One day in the Granite Creek country nearby I counted 11 grizzlies—all in sight at once. But I had never seen one near as big as that black animal.

I’d tried several times during the summer to ford the river so I could get at him, but the Delta is mean to cross—its glacial water deep and swift—and I was forced back every time. It stayed high right until freeze-up that fall, too. But that August day I made up my mind to get that bear, and began trying to figure a way to cross the river. As it turned out, I never did make it that fall.

One morning a week or so later, I heard my sled dogs marking. A grizzly or a caribou wandered near the roadhouse occasionally, so I grabbed a rifle and stepped outside. Instead of game in the yard there were two dogs. But what dogs! Big and wolflike, they weighed about 120 pounds each—twice the weight of the biggest of my three sled dogs. They were both males and I thought they might fight my chained dogs, so I decided to run them off.

“Git,” I yelled and heaved a rock at them. They dodged and sat looking at me. After they had dodged two or three more rocks and showed no sign of leaving (or of fighting, either) I gave up.

“C’mere, then,” I called. They ran up to me, wagging their tails as though they’d known all-along they’d be welcome. I tied them up, thinking their owner would probably be along looking for them.

That fall three cars managed to bounce their way over the rough trail—all Ford Model T’s. I asked the drivers to spread word up and down the road about the dogs. Freeze-up came and no one had claimed them. I needed a couple more sled dogs anyway, so I didn’t really mind. I named them Yukon and Red.

The first time I harnessed them with my three dogs the big dark fellow, Yukon, calmly stepped into the leader’s position. None of my dogs were much good as leader, so I left him there. We started off, and just to try him, I softly said “Gee!” He didn’t hesitate a second but whirled in his tracks. He made a fine leader—always seemed to pick the best going and answered commands right now. Besides, he pulled like a horse and somehow pepped up the whole team. Ordinarily, pushing a sled and yelling at mule-headed sled dogs is hard work; but with Yukon at the lead and Red pulling at the wheel, I actually enjoyed traveling.

THAT WINTER, as usual, I trapped across the river. Fox skins brought good prices, and I enjoyed getting out too. Cold weather didn’t’ stop me at all. One day along in February, when patches of fog lay here and there, as they always do when it’s real cold—it was at least 45 below that day—I was across the river driving the team up a box canyon. Almost always there’s enough breeze in a little canyon like that to keep the willows free of frost, but this day I noticed a little patch of frost-covered willows up on the side of a steep slope. I couldn’t quite figure it out, so I stopped and looked it over with my glasses. There was a bear den right below the willows, and the bear’s breath was freezing and piling up on them. Now I wonder—maybe it’s the big fellow, I thought. I’ll just have to watch and see.

From then on, every time I went past there, I’d stop and look with the glasses. The bear stayed denned up through Frebruary, March, and April.

On the morning of May 6, 1922, I stepped out of the roadhouse, rifle in hand and a light pack on my back. Winter was leaving the rugged Alaska range; snow was melting, it was warm, and I wanted to be out in the hills. Any excuse would do. I told the Hammonds, a couple who were operating the roadhouse for me, that I was going to cross the river to see if the bear was still in his den. I was in the habit of taking a couple dogs with me on my hikes, so I turned Yukon and Red loose.

There was still good ice on the river, even though several inches of water was flowing over it, so I crossed and started up the mountain. Long before I got to the den I could see a trail coming out of it. The bear had cleaned his den out, and part of the dirt had rolled down the slope onto the snow. The tracks leading from the den were so enormous I was sure they could have been made by only one animal—the black grizzly.

Instead of leading the bear to me, the dogs took the mad and bawling critter right past me. I twisted around as they passed within 15 feet and fired without aiming. The bear kept right after the dogs—just boiling mad and blaming them for his troubles.

I spent 10 minutes reading sign there at the den. He’d loafed around for several days after waking up—coming out and lying in the sun during the warm days, then crawling back and sleeping in the den at night. Fresh tracks led up the box canyon; they didn’t look more than two hours old. Sheer cliffs rose from both sides, and I knew that the canyon ended abruptly in a wall about a mile above. The bear was trapped!

Three inches of snow had fallen during the night. This made for good tracking, but what with fresh snow on top of the hard-packed old drifts it also made the floor of that steep canyon slicker than grease. I buckled on a pair of steel ice creepers I always carried in my pack, and started on the fresh trail. That bear laid the biggest tracks I had ever seen! He walked kind of pigeon-toed, and the tracks were spread almost two feet apart. He had a good three-foot stride, too.

His big claws—and they were big—showed in every track in that fresh snow. I was sorry then that I had the two dogs with me. I figured that if I jumped the bear they’d be an awful nuisance, and I considered taking them back to the roadhouse and returning alone. Then I decided not to, for if I jumped the bear at close range they’d probably high-tail it home anyway—sled dogs usually don’t care much about fighting bears.

The dogs kept trying to break ahead of me and seemed anxious to take off on the track. I couldn’t figure them out and began to get a little anxious for them. The canyon narrowed down. The bear was in it, I knew, and couldn’t get out except by passing me. I didn’t know where I’d run into him, but I sure hoped I’d have enough time to kill him before he got to a dog—if they were foolish enough to tackle him.

The tracks led up the middle of the canyon for about half a mile. Then I could see where the bear had tried to climb out; there were steep gulchlike chimneys here and there in the canyon wall and the bear had tried them all. He would go up one until it got too steep for him, turn, and slide down; then go on and try another.

It was getting harder to hold the dogs back. I didn’t want to make any more noise than necessary, so I had to “shout at them softly” as they crowded me. I really began to get keyed up. I wanted the bear, but didn’t want the dogs to get hurt. Once in a while the warm sun would cause a rock or a bunch of snow to slide down the side of the canyon and every time that happened I’d whirl, expecting the bear. What got me, though, was the way those dogs acted. They’d dash right at each slide, bristling and growling. They sure acted differently from any sled dogs I’d ever seen.

We came to the last bend in the canyon. The bear wasn’t in sight. I could see all the lichen-encrusted walls that formed a tight box out of which nothing could climb. The floor of the canyon was 25 or 30 feet wide at the end, and there was absolutely no cover there.

I stood still, puzzled, looking at the tangle of fresh bear tracks. He had gone to the end of the canyon and returned half a dozen times, circling and looking for a way out. Opposite me was a narrow gash in the wall, where another chimney went up out of sight. It had a good 35-degree slope and was four or five feet wide. I knew from experience that it ended in a sheer cliff.

“Damn!” I said as I looked closer. The bear’s tracks were in the chimney—going up, but not coming down!

I heard rocks clatter, then saw loose snow and stone bounce around the bend in the chimney, right above me, not over 30 feet away. Suddenly, heading straight for me, almost filling the chute, came the bear—sitting and sliding. He evidently didn’t realize I was around. That black, silver-tipped skidding bear looked bigger than—well, like the whole damned mountain coming down. I threw the .30/06 rifle up, but before I could shoot, Yukon and Red bounded past me to meet the bear.

“Yukon, Red, come back here, damn it!” I yelled, trying to get a bead on the bear at the same time. I’d probably have got in a good shot, too, because the bear was sitting, and his chest was up where I could hit it. But those crazy dogs got in the way and I had to shoot to one side.

Wham! The echoes in the canyon almost deafened me. I broke the bear’s left shoulder that first shot. Just as I fired, Yukon met him head on, and the startled bear swiped at him with a paw the size of a siwash snowshoe—and missed!

The bear roared with surprise and pain as the slug and the two dogs hit him at the same time. He and they rolled on to the floor of the canyon, right to my feet. It all happened in a flash. I was so flabbergasted I didn’t have time to move—probably couldn’t have if I’d tried.

The bear picked himself up, looked around s though he couldn’t believe what was happening, shook himself all over, and beat it down the trail as fast as he could—the dogs swarming all around him. I could see for 70 or 80 yards and tried to line the rifle on him. Every time I did a dog flashed by, so I didn’t get to fire. Then, bear bawling and dogs growling, they disappeared around a bend.

I started to run towards them and had gone about 50 feet when I saw the dogs coming back, running hard, the bear right behind them. And they were headed right for me.

I skidded to a stop, raised the rifle—and one of my creepers slipped. I landed flat on my back, with both feet in the air. I expected the dogs to dash in behind me, trying to get me to pull the bear off their tails, and for the bear to climb all over me any second. It was a lucky thing I’d broken one of his shoulders with my first shot—now the dogs could outrun him. Otherwise I think he’d have caught them in that small canyon.

Instead of leading the bear to me, they took the mad and bawling critter right past me to the head of the canyon. I twisted around as they passed within 15 feet and fired without aiming. The bear lurched. Gosh, he looked big! He kept right after the dogs—just boiling mad and blaming them for his troubles. They ran to the end of the canyon, where the bear sat up and faced them, swatting at them with his one good paw.

I go to my feet, set the creepers firmly in the packed snow, and watched for an opening. Every time I was ready to shoot, though, a dog got in the way. I groaned in exasperation and stood watching the dogs. Neither had been touched, and they were having one hell of a good time. Red would work behind the bear and actually leap on his back, slashing at him all the while. Yukon danced back and forth in front, keeping him busy. And then it finally dawned on me: they were experienced bear dogs! They worked as a team, one keeping the bear busy while the other dived in and ripped at him.

I figured the bear would make another break for it, so I backed up to the canyon wall to give him plenty of room to go by. I still couldn’t seem to line the sights up on a vital spot. Once I threw the rifle to one side when Red dashed across just as I fired. I’ll bet I didn’t miss that dog by two inches. The slug caught the bear in a hind foot.

He started down the canyon again, the dogs growling at his heels. I swung and snapped a shot as they went by. Before long they came back again, the bear chasing the dogs. The big brute bounded along on three legs, his lips curled back, and his big white teeth showing with every jump. Again I slammed a shot into him as he slipped by. He passed so close to me I could see individual hairs in his rippling, silver-flecked hide.

This happened twice more and I got in two more quick shots. Once the bear was in the lead, and next time the dogs were hotfooting it out front, tails between their legs and heads over their shoulders, egging the bear on.

Every time I fired, loud echoes slammed back and forth in that little canyon. The roaring and bawling of the animals sounded unreal. Finally they stopped not over 20 feet from me and the bear sat up once again to face the dogs. He was getting weak. He squatted, his mouth open, his left leg dangling. Blood oozed from half a dozen places on his black hide, and the canyon floor looked as though a sprinkling cart had run up and down it spraying blood. I could hear the grizzly panting, and every few seconds he’d let out a horrible bawl. He flexed his right foreleg, holding it high, his 3 ½-inch claws standing straight out. Then he’d forget about his broken left shoulder, lunge in an effort to scoop a dog into his mouth—and land almost flat on his face. I could almost feel the ground shake when he hit. Then Red would climb on his back, growling, dancing, and slashing with those wolf teeth of his.

“Easy, boys, easy! Let me have him. Get back Red, Yukon, get out of the way,” I yelled, trying for an opening as the dogs danced in and out, slashing at the bleeding and reeling bear. I saw my chance and fired. A chest shot! The bear dropped, belly down, and lay there. He raised his head, lowered it, raised it again—game to the last. A final shot in the neck quieted him for good. The two dogs climbed on him and wooled him some more.

“Where’n hell did you dogs learn to fight bear like that?” I burst out at them, in relief. “You two crazy mutts damn near got us all killed, but you seemed to enjoy it!”

THAT BEAR was a monster. The hide, after I peeled it off and packed it home, squared out 10 feet 8 inches on a side. The big, dark, lustrous fur was tipped with silver, and it was as fine a trophy as I’ve ever seen. The skull, cleaned later and measured while it was still green, was 17 inches long. I didn’t measure the width.

About the middle of June I was replacing some chinking on the front of the roadhouse when a Model T pulled up and stopped. I looked up, waved, and started towards it. In those days, cars were few and far between in Alaska. The driver—a fellow with straw-colored hair—climbed out, then stiffened suddenly as he saw Yukon and Red tied to the side of the house. He ran over to them, stooped over, and hugged them to him, petting them and making a big fuss. I walked over, and the guy stood up with a grin on his face.

“You know those dogs, mister?” I asked.

“Sure do,” he said. “They’re mine. My name’s Elmer, from down Slate Crick way. I’ve got some placer diggin’s down there and these dogs wandered off last fall. I’ve wondered ever since what happened to them.”

They were part of his team of Victoria Land dogs, it seemed, and he’d kept them at the mine as watchdogs for his kids. They ran loose, played with the children and kept bears from wandering around camp. Elmer had left the rest of the team at Valdez, where he lived winters. It turned out, too, that the one I called Yukon had been his leader. One day they had followed a packer from his mine out to the highway and then had wandered on down the trail 40 miles or so to my place.

When I told him about the way they had handled the big grizzly Elmer said, “That’s nothing. You ought to see the whole team tackle a bear. Those Eskimo dogs from the Canadian arctic are the best damn bear dogs in the world. They have to be, or they don’t last long up there.”

I sure hated to see them go. Until later years, when I got my own wolf-dog leader, Yukon was the best leader I had.

Several people who saw the big bear hide wanted to buy it, but I wouldn’t sell. It was legal in those days to sell bear hides, and I was willing to part with any hide I had—except that one. A road-commission man offered me $150 for it, but I turned him down. That fall I guided a party of sheep hunters into the Jarvis Creek Country, and when I got back, Mrs. Hammond met me at the door.

“I sold that big bear hide to the editor of Outlook magazine,” she said. “He was traveling through and happened to see it. Here,” she said proudly, handing me a slip of paper, “I’ve got a $100 check for you!”

Read Next: My Lady Judas: The Wolfdog That Called in Wolves for Frank Glaser