There’s no shortage of opinions when it comes to wolves and their place in the environment. In a time with increased introductions of wolves and natural expansion of introduced populations, human-wolf conflict will likely continue to increase in many forms. But how likely is it that people will be attacked and killed by wolves? In 2010, a school teacher in rural Alaska was killed and eaten by at least two wolves while out jogging, and in the early 2000’s, a wolf attacked a woman in a campground along the Dalton highway who escaped by getting into a campground restroom.

As to whether-or-not aggressive encounters may be normal, I find the insight of legendary Alaskan and federal wolf hunter Frank Glaser fascinating. He spent decades hunting, trapping, and observing wolves, and even captured and bred them with sled dogs. This story was originally written in Outdoor Life by Jim Rearden in the October 1954 issue. Glaser’s stories are incredible because of the first-hand wisdom and experience he possessed. Many of his stories include detailed side stories that add value to his experience. So, will wolves attack a man? Here’s what Glaser had to say. —Tyler Freel

Will Wolves Attack a Man?

By Frank Glaser, as told to Jim Rearden

IN APRIL 1933, Moose John Millovich left Fairbanks, Alaska on a beaver-trapping expedition to the Beaver River in the White Mountains. some 75 miles to the north. A friend drove him part way—to Olnes, a little mining village. From there Moose John, a man about 60 years old, pulled a sled 50 miles north, bucking spring snow through the rolling hills and low tundra to the big bend on the Beaver. Moose John had lived on the river before and was an experienced outdoorsman. Neither he nor any of his many friends foresaw any possible danger to him.

He was expected back in Fairbanks in late May, but July rolled around, and he hadn’t showed up. Two of his Fairbanks friends, George Bojanich and Sam Hjorta, hiked to the Beaver to look for him.

They found the door to Moose John’s cabin open. The dates on a calendar were marked off through May 9. There were burned hotcakes and burned bacon on the stove. The table was set with clean dishes and silverware. But there was no Moose John.

The two men searched upstream and down for several miles, thinking that their friend might have fallen into the river and drowned. After three or four days of fruitless scouting they were about to give up. About all the sign they’d found was the wolf tracks around the cabin. Wolves occasionally howled from the hills as they went about their futile search.

They finally sat down and reasoned that the missing man must be somewhere near the cabin, since he obviously wouldn’t wander far while cooking breakfast. So they started circling the cabin, covering the ground inch by inch.

One of the men found a human thigh bone less than 30 feet from the cabin, under some large spruce trees growing in a stand of knee-high redtop grass. It had been cracked open as by a powerful-jawed animal. Soon they found a human skull with part of the hair and scalp still attached. Then other bones were found near by.

George Bojanich told me later that all they found of the trapper just filled a five-gallon can. The ribs and all the small bones were gone. His clothes had been widely scattered through the gloomy spruces, and there was an occasional bone clinging to them by bits of dried flesh.

Bojanich and Hjorta decided that wolves had killed Moose John. There were certainly plenty of wolves in the White Mountains at that time. Bojanich had trapped in that region for marten just the previous year, and the howling of the wolf packs had made him so jittery that he was glad to leave in the spring. Those wolves get hungry when the caribou aren’t there-which is often-and they do become bold.

Perhaps they did kill old Moose John. No one will ever know. Wolves certainly ate him. His bones were cracked open-almost positive evidence of wolf work-and wolf sign was all around the cabin. The biggest of grizzly bears would never have broken those bones.

I thought about that incident for a long time. George Bojanich told me every detail when he and Sam returned after burying Moose John’s remains. Also, a few years later, I spent a winter in Moose John’s cabin. Bojanich and Hjorta had buried the can holding the trapper’s remains about 20 feet from the door-in front of the only window. I spent hours sitting at that window, eating, writing, and reading, and every time I glanced out I saw the cross over the grave.

Although Bojanich, Hjorta, and many others believe wolves killed the old trapper, I don’t think so. There are many possible explanations of his death. He was in his 60’s, and he might have died of a heart attack while throwing out garbage near the cabin. Wolves could have found him dead there. An incident that occurred when I was staying at the same cabin on the Beaver River a couple of years later suggests an even better explanation.

It was May, just about the time of year that Moose John met his end, and I was trapping wolves. One morning the snow had a good crust on it, and I traveled eight or nine miles up a little creek on snowshoes. By noon the sun had softened the snow so that I couldn’t use the webs any more, so I started back toward the cabin, hiking along the mountainside. On the way I came to a big rockslide. where there was practically no snow. I started across it, my snowshoes under one arm and rifle slung across my shoulder.

It was tricky footing in that loose, slick, shale. I was wearing moccasins, and had to watch every step. When I got almost to the middle of the slide I heard a noise and looked up to see a grizzly sitting on its haunches and looking at me, like a big dog sitting up and begging. I let out a war whoop, figuring the bear would leave. I’ve met literally hundreds of grizzlies in my 50 years of trapping. and normally a yell or two will send the biggest bear high-tailing. This one just sat.

I let out another whoop then and continued walking. I still didn’t put my snowshoes down, or even get my rifle ready. Then the bear let out a growl or two and started toward me. The slope was steep, and a lot of rocks started rolling as the bear came half sliding and half jumping down the slope toward me. By then he was about 60 feet away. I was taken completely by surprise, depending too much on what bears are supposed to do.

I jumped back so the rocks wouldn’t hit me and dropped the snowshoes. The grizzly was practically on top of me when I threw the gun up and fired without aiming. His momentum carried him past and not more than six feet in front of me.

He reached the bottom of the slide, picked himself up, and started back toward me. That puzzled me. He was hit in the chest, and would no doubt have died in a few minutes. Most bears would have kept right on going—even more likely, most bears would never have charged in the first place. As this one struggled uphill toward me, growling and grunting, I took my time and shot him in the neck. He stopped then, dead.

Later I learned that other people have had somewhat similar experiences with grizzlies in the White Mountains. The bears there are just aggressive, that’s all. I don’t know why.

Moose John had trapped eight or nine beavers before he died and he didn’t have any dogs to eat the carcasses. He probably had thrown the skinned bodies—the best kind of bear bait-in the snow in front of the cabin. Bears usually have been out of hibernation for a week or so by May 9, when he had stopped marking the calendar, and I suspect that one of those aggressive spring-hungry grizzlies was feeding on the beaver carcasses when, for some reason, Moose John drew near him without a gun and got swatted down. I think it’s much more likely than wolves killing him.

In all of my experience with wolves—including 17 years as a government wolf hunter—I have never seen wolves start to tackle a man except in cases of mistaken identity. And when they see their mistake they’ll back off. Most wolves won’t even try to get at you when they’re in a trap.

One June, walking along the Alaska Range with a couple of my three-quarter- wolf dogs carrying packs, I stumbled onto a pair of wolves. I had left Wood River and was plowing through a thick mass of dwarf birch when two gray wolves howled just ahead of me. Then I saw their heads poke out of the brush 20 or 30 yards away.

They’d heard me coming and probably thought I was a caribou. The moment they howled my two dogs lit out after them and the wolves disappeared. They probably had pups, and perhaps I was close to their den. I’m sure if they had realized what I was they wouldn’t have shown themselves.

Another time I was snowshoeing along at the edge of some timber when suddenly I heard animals running in the snow behind me. I turned and saw three black wolves coming right for me on a dead run. By the time I flipped my parka hood back, pulled my mittens off. and had my gun ready, they had wheeled back into the timber.

I went back to see what had happened. Their tracks showed they’d been loping along slowly, and apparently heard me walking in the timber before they could see or smell me. They must have thought they were going to cut off a moose or a caribou when they started to rush me. The moment they saw their error they whirled in their tracks-running faster to get away than they had to overhaul me.

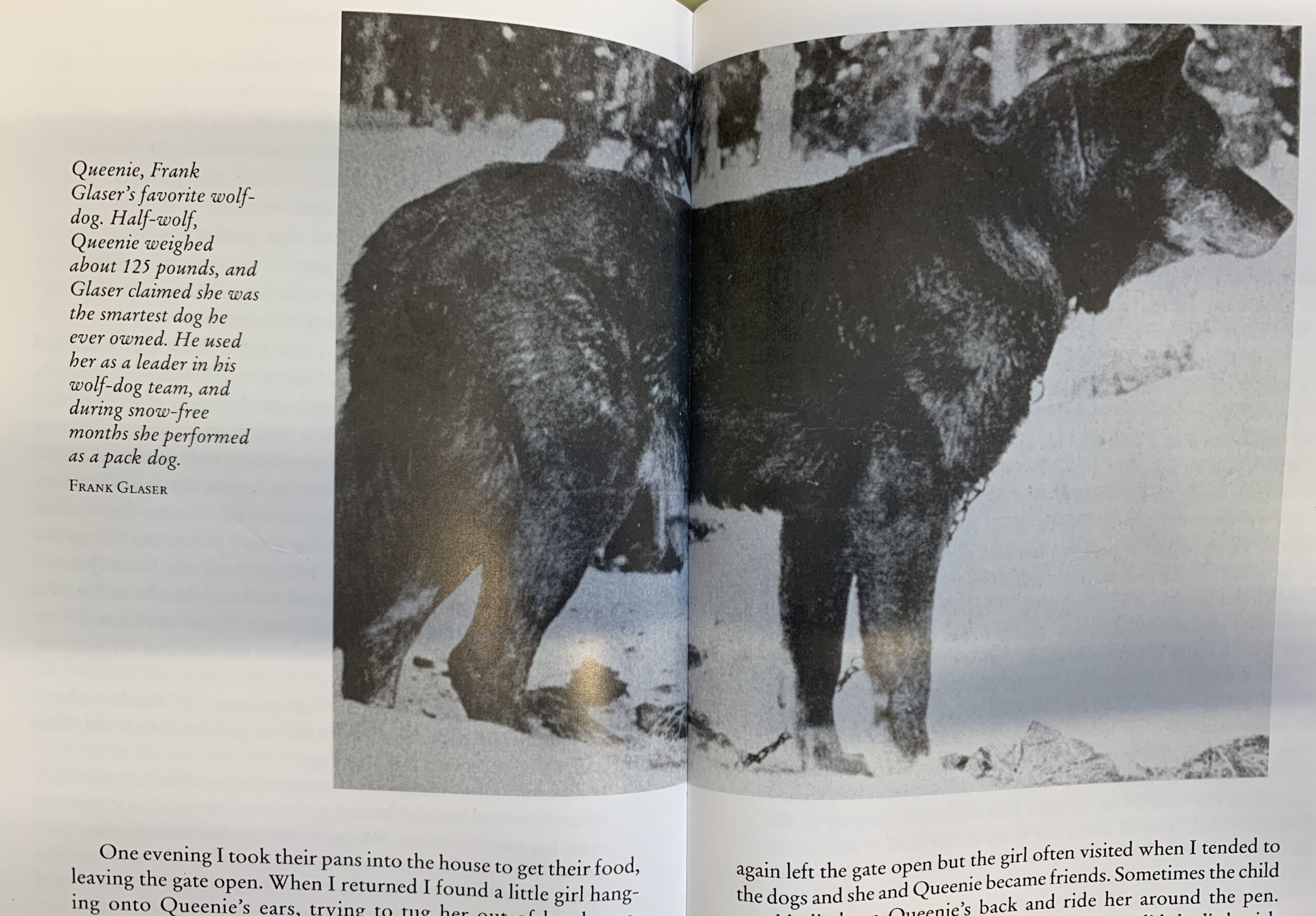

Wolves are great to follow sled dogs, too. For years I owned a team of wolf-dogs, and perhaps that’s an even greater attraction than a team without wolf blood, for many and many a time wolves have followed my dog-sled trail for miles.

Years ago, before the passage of Alaska game laws, trappers commonly killed caribou throughout the summer for fresh meat and dog food. I usually waited until the cool of evening. Then I’d go a few miles from the cabin and kill a bull caribou, dress it out, and haul it home with my dog team and a wooden-runner sled that worked pretty well on grass and gravel. One evening I arrived home about 8 o’clock with a big bull on the sled. I leaned my rifle against the corner of the cabin, tied my dogs to their houses, and started back to the sled to hang the meat. Suddenly I noticed the dogs looking toward the river, wagging their tails, straining on their chains. There were three black wolves sitting there, not over 20 yards away.

Wolves seem to sense what a man is thinking and doing. I ignored—or pretended to ignore—these three. Slowly and nonchalantly, I walked to the cabin and picked up the rifle. Then I whirled fast, ready to shoot. I think the wolves started moving as I turned my back. By the time I had one centered in the scope he was just jumping off the riverbank to a sandbar. I dropped him into the river, dead. The other two sprinted down the bank and I blew geysers of gravel up all around them, missing about two shots at each of them before they disappeared. It was pretty light all night at that time of year and I was curious, so I walked back to where I’d killed the caribou on a river bar. I found tracks in the sand where the wolves had hit my sled trail a few hundred yards from where I loaded the bull. There were drops of caribou blood along the way, and that probably attracted them, but my tracks were there, and scent too, no doubt. The wolves had come trailing right to the cabin, and on a dead run. Why, I do not know. Wolves are the only animals I know that identify, by sight, a man that is sitting still. Several times I’ve had them identify me when the wind was in my favor and I was absolutely motionless, leaning against the base of a tree or rock. Moose, caribou, and bears especially bears-can look square at you from 20 or 30 feet away without recognizing you, if you don’t move and the wind is in your favor. Not wolves. They’ll stare at you for a moment, identify you as a man, and high-tail it out of the country.

But I do know one case of a wolf attacking an Eskimo. I investigated it personally and know that this wolf wasn’t fooling. But the facts go beyond that. It’s an interesting story.

Punyuk was the Eskimo’s name (old-time Eskimos had only one name, generally) and he lived at Noorvik in the Kobuk River country. I was living at Kotzebue, about 60 miles away, at the time he was attacked. Miss Marge Swenson, teacher-nurse at Noorvik, had a daily radio contact with Kotzebue. She asked, during one of these contacts, for me to come to Noorvik to investigate the case.

I hooked up a dog team and drove to Noorvik, taking two days for the trip. It was January, cold, storming, and mostly dark as the north is at that time of year. I arrived four days after Punyuk had been attacked.

The evening I got there Miss Swenson went to Punyuk’s house to change his bandages, and I went along to hear the story from the old Eskimo himself. He lived in a small, crowded, log cabin, which is unusual in that barren country where logs have to be hauled many miles. Punyuk was lying on a low couch when we entered the lamp-lit, smoky cabin.

Punyuk was 63, and he knew only a few words of English. His married daughter, who assisted Marge Swenson at the school, acted as interpreter. Here’s the story as she translated it for me.

Punyuk had been living in a stove-heated tent and trapping on a ridge that pokes out between the Kobuk and Selawik Rivers. He had his dogs tied to some willows near the tent. Sometime during early evening (it gets dark about 2 o’clock at that time of the year) he heard his dogs growling and making a fuss. Stepping outside, Punyuk saw what he took to be one of his dogs, loose. It was dark, but the moon and stars reflecting from the snow gave a fair amount of light. He picked up a chunk of ice from a pile he kept to melt for cooking and drinking and threw it at the “dog,” ordering it to come.

When the ice hit the animal it rushed Punyuk, jumped up with its front feet on his shoulders, and bit at the top of his head. Of course Punyuk realized then that it wasn’t one of his dogs, both from its actions and its size—it was twice as big as any of his dogs—and he knew right away that he was dealing with a wolf.

When the wolf found it couldn’t yank that chunk out of Punyuk’s leg it let go, and Punyuk struggled to his feet. But the wolf jumped up and grabbed his shoulder, biting twice clear to the bone.

The animal knocked him down and started chewing on his head. It ripped three or four places clear to the skull, and tore the whole length of his scalp before Punyuk grasped the animal’s throat and managed to get his knees on it and choke it down. He got a small pocketknife out after the animal had relaxed a bit, and slashed with it a few times. He didn’t stab.

He stood up then, looked closely, and saw for sure that it was a black wolf. He didn’t try to finish it off.

Figuring that a trapper normally has a pile of wood outside his tent, I asked his daughter, “Did he have some stovewood there?”

“Yes.”

“Then why didn’t he hit it with a piece of that and kill it?”

She talked with him for a long time then, and he seemed reluctant to tell her. Finally she said, “My father cannot kill a black wolf.”

That puzzled me at the time, but I learned later Punyuk belonged to what is known as a wolf clan. Many of the older members believed that when some old village grandmother died her spirit would go into a wolf, preferably a black wolf. To kill one for those people, was like killing a respected old woman. This wasn’t a fairy tale to those old-time Eskimos; they believed every word of it.

Punyuk stood over the black wolf he had choked into unconsciousness until it revived, making no move to harm it.

“Oh, you have hurt me enough, grandmother,” he said. “Now go and leave me in peace.”

As his daughter translated this I tried to picture simple old Punyuk standing in the arctic moonlight, his scalp torn loose, blood running down his head and face, talking to the wolf. I didn’t laugh.

The wolf got up and grabbed Punyuk’s right thigh and sank its teeth in deep. The Eskimo had on a pair of overalls at the time, having just stepped from the heated tent; with sealskin pants, his regular outdoor clothing, he’d have had better protection.

The wolf actually lifted him clear of the ground and threw him down, then placed its forepaws on him and pulled. trying to tear a chunk out of his thigh.

Marge Swenson dressed the wounds as Punyuk related the story. It made a strange setting in the dim light of the tiny cabin, and the old Eskimo’s guttural tones emphasized the bizarre tale he was telling. He didn’t wince as Marge pulled the blood-stuck bandages free and probed to drain his wounds.

I could see bone in the two main holes in his leg where the wolf’s upper canines had entered. On the opposite side, where the two lower canines had sunk in, I could see a couple of cords the teeth had caught as the animal tried to pull out a chunk of meat. They were terrible wounds.

When the wolf found it couldn’t yank that chunk out of Punyuk’s leg it let go, and Punyuk struggled to his feet. But the wolf jumped up and grabbed his shoulder, biting twice clear to the bone. Then it tried Punyuk’s head again, driving one tusk in just above his ear. If it had been a little lower it probably would have killed him. Evidently Punyuk passed out then, for his daughter told me, “My father didn’t know any more.”

When Punyuk revived the wolf was gone, and the dogs were barking and making quite a racket. He dragged himself into the tent and washed the blood off, bandaged himself crudely, and put on his fur clothes. Then he crawled around until he got his dogs harnessed to the sled and he sprawled on it as they pulled him into Noorvik.

When Punyuk told the story to his two boys, they immediately harnessed a dog team and left to track down the wolf. They didn’t believe in the old superstition.

The wolf bled a little, and had staggered and fallen down a number of times. Several times it went out of its way to attack a lone spruce tree and chew limbs from it.

The trail zigzagged to the village of Kiana, about 12 miles from Punyuk’s camp. When the boys got there they learned that someone in the village had killed the wolf as it was eating some malamute puppies.

I got this news from Louis Rotmann, a white trader, and the day after Punyuk told me his story I went to Kiana. The wolf had been skinned, but I found the carcass and cut off the neck and head. The animal was an adult, in excellent condition. He’d have weighed more than 100 pounds.

I turned the wolf’s head over to Dr. Bauer in Kotzebue, and he sent it out for laboratory analysis. For some reason the laboratory report didn’t get back to Kotzebue for several months, too late to help Punyuk. In March word reached the reindeer camp I was in that the old Eskimo was dead. He had apparently recovered from the wolf’s attack, then had died suddenly while lying on the ice and fishing for arctic sheefish.

A month later the laboratory report confirming what 1 had suspected—that the wolf had rabies—came through. By then, of course, all the excitement had died down, and many people, in saying that Punyuk was attacked by a wolf, will let it go at that. An account of this incident, in a national magazine, said Punyuk died of his wounds shortly after being attacked by a wolf. Period. Rabies wasn’t mentioned.

I don’t know of a single proven instance of a normal wolf attacking a human. And I have tried to learn as much as possible about every reported attack in Alaska since 1915. Wolves just don’t take to people. Even when captured as pups, before their eyes are open, they don’t gentle well. I once caught a young wolf in a trap and took it home to use for breeding purposes. I even broke it to harness and drove it, but I could never trust it.

A few years back I discovered a wolf den on the Chatanika River, north of Fairbanks 50 miles or so, and managed to kill several of the half-grown pups. I told Ted LaFon, who was watchman at a big mining siphon near the den, and suggested that if he waited until May the following year the pair might come back and he could get that litter of pups. He did, and brought in 13 of them. He sold a number of them alive to people in Fairbanks.

I was in Nome at the time, but the next fall I came into Fairbanks in November. As I started to go into the Nordale Hotel for a room, I was astonished to see a big gray wolf crouched in front of the doorway. A woman was holding it on a leash.

“That’s a nice wolf you have there, lady,” I said, as I took the leash and skidded the animal aside to walk in.

“It isn’t a wolf; it’s a dog,” she shouted after me as I went up to the desk to register.

I read in the paper that night that the city council had called a special meeting to warn two or three people who had these full-grown, full-blooded wolves to get their wolves out of town or they’d order them destroyed.

The wolf I hauled out of the Nordale doorway was scared to death. I could see fear in its eyes, and it was flattened out there afraid to move. That’s a dangerous situation-a half-tame wolf. No telling how an animal like that might react if a youngster pulled its tail or something.

The Fairbanks city council was right. But a wild wolf is different. As long as a man is alive, I think he’s safe from attack by wolves in the wild.

Read Next: The Best Shot I’ll Ever Make: Fred Bear’s World-Record Stone Sheep, from the Archives