Something monstrous was about to happen. You could feel it coming. Boats were out trying to drag enormous sharks from the deep. A crowd waited, eager to see the apex predators that swim in the North Atlantic hung up back at the dock. The scene was so retro it was as if a black-and-white documentary about shark fishing was playing out right there in 3D color on this pier in the swanky town of Newport, Rhode Island.

If you don’t know Newport, picture a Hollywood set of an idealized coastal New England village. The main drag is all seafood restaurants with gaudy ship anchors and wheels as trimmings, nautically themed boutiques with glamor in their storefronts, and pubs festooned with dark wood and brass taps. Each cross street ends in a pier. A few have real fish markets on them. Most have yachts bobbing off them.

People were saying Celine Dion was on one of the big white yachts with the mirrored windows and spacious sundecks—one of the boats without outriggers. Everyone nodded when they heard this, as if it must be true. How could you have such a scene without a celebrity endorsement?

All around, the extras were strictly upper class. Women wore designer dresses and carried fancy bags. Men donned blue blazers with gold buttons and crisp white oxford shirts. Some of them actually had sweaters tied around their necks. They were all coming off the chic street along the blue bay in hopes of seeing monsters.

Of course, hundreds of shark fishermen (and their families) were in town, too; though few evoked the character Quint from Jaws. These were mostly men from New York or Boston who have the spare change required to run a boat 50 miles off the coast for a day of fishing for sharks or tuna. Some fancy themselves as throwbacks—iconic playboys in an age when such men were cultural manifestations of class and rugged appeal, an era when Errol Flynn, Jack London, and Humphrey Bogart took their big boats out to the blue water for giant fish. Still, the Monster Shark Tournament is a kill tournament. Its captains might be mostly well heeled, but they’re not afraid of getting shark blood on their office-smooth hands.

To add spice to the already flavorful scene, PETA had threatened to show up and do who knows what. I was told that the year before—when the tournament was still on Martha’s Vineyard—20 animal-rights activists tried to pick a fight with the tournament goers, prompting some of the spectators to yell colorful things back. It didn’t escalate further, but parents were forced to put their hands over their children’s ears.

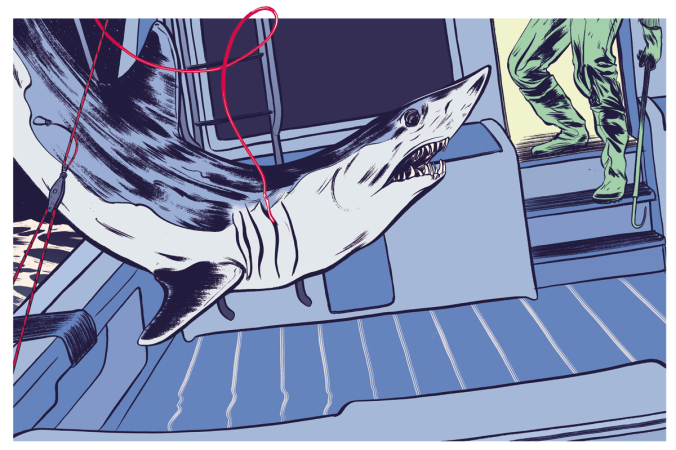

I walked down the pier and past cops who waited like bouncers for those jokers, but none showed up. A voice on the loudspeaker told everyone that the monster sharks were coming. Fishing boats would soon pull up one by one, with big, dead sharks on them. These sharks would be hoisted up, blood dripping, by a crane with a long steel cable and hook. The sharks would be weighed on a scale that was officially calibrated to satisfy International Game and Fish Association (IGFA) standards—records, after all, might be broken. The biggest mako, thresher, or porbeagle would win the day, but not necessarily the event. There was still another day of monster shark fishing to be done in these waters.

In Memoriam

There was a heavy-hearted undercurrent to the otherwise festive and lively scene. For its first 27 years, the Monster Shark Tournament was run by Steve James, president of the Boston Big Game Fishing Club (BBGFC). In the shark-fishing world, he was as famous as Frank Mundus. But James had drowned in a duck-hunting accident in January 2014, six months prior to the 28th annual tournament.

Now, James’s family—his mother, uncle, aunt, niece, nephew, and cousins—had come to put on this tournament as a dedication to a man who they say had always been larger than life. You could feel the love for him in everyone on the pier. The fishermen told stories about Steve’s safaris and shark tournaments and the times he went to state capitol buildings to tell lawmakers why they should vote this way or that for the sake of the sharks and the world of which we are a part.

“He was a man’s man,” said one.

“There aren’t supposed to be men like Steve anymore. A total Hemingway type,” said another.

“Steve was an adventurer,” said his mother, Doreen James, as we looked out at a boat coming in with a shark. Her eyes were proud and moist with a mother’s loss. “He’d hunted all over the world. He loved catching huge sharks on rod and reel. He was a gentleman. He was all that a man should be. He was my son.”

The Weigh-In

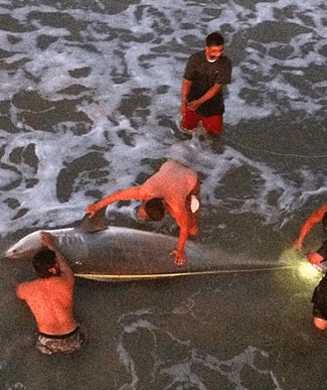

The first shark in was something of a disappointment—just a 100-pound mako. “I had to kill it,” said the captain apologetically. “It couldn’t be revived.”

Several biologists weighed and measured the shark and took samples. “I go to shark tournaments up and down the East Coast,” said Lisa Natanson, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), as she pulled on arm-length rubber gloves, slit open the shark’s stomach and reached in to see what it had been devouring. “Without these tournaments we couldn’t learn all that we do about sharks. And, really, the anglers don’t kill many sharks. These tournaments are good for sharks.” She pulled out a fish head. “Well, this one was hungry.”

More boats showed with threshers and makos. None were huge. Little kids pushed through the legs of ogling adults. So many climbed onto the base of a nearby crane to see over the crowd that the dock’s owner begged people to get back, but eventually gave up as the tide of people washed over him.

This next boat in wasn’t like all the pretty white yachts in the harbor. It had an open deck and a cabin without the plush bars and couches in many of the other boats. Suntanned men in rubber boots stood on the boat’s deck. You could tell they fished for a living. They came in slowly as the announcer threw suspense into the microphone and people pushed forward to see.

This boat, the “Magellan,” was captained by Frank Greiner Jr. They tied up and the crane hummed and dropped its hook. Up came a 429-pound porbeagle, a big-headed shark that likes the cold, deep waters of the North Atlantic.

Mouths were agape. The fishermen posed. Cameras flashed. These fishermen didn’t have salty beards and sou’wester hats, but they did have the hardy look of the New England fishermen Sebastian Junger humanized in The Perfect Storm a century after Rudyard Kipling’s Captain’s Courageous set the archetype. They’d toss their heads at that characterization, but amidst the chic vacationing crowd they stood apart.

The Crew

The next morning I left the dock hours before sunrise onboard “Waugh’s Up.” When the day dawned on the Atlantic, we were 70 miles out. The 55-foot Viking’s engines slowed and fishermen began dumping chum along a contour line marked on the bottom. I’d ridden out in order to get into the sharks with some of the tournament’s contestants, but I had no idea I’d join a crew like this.

The captain, Brad Waugh, was once the president of Life Alert, best known for its “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up” commercials. Waugh left Life Alert for other ventures when he saw smart phones coming. But all that business success was back on land. Out here, he was with his handpicked crew. He’d met them one by one. Their backgrounds varied from blue collar to white, but none of that was evident on “Waugh’s Up.” What was clear was that they’re a team.

Brad runs the boat. He’s a medium-sized man with charisma, and people listen when he speaks. Kyle is a graying ex-Marine who’s still built like one. His job is hooking and playing the sharks. Then there’s Chris—heavyset with strong, calloused hands he’s earned as a commercial fisherman. Chris sets the rods and confers with Brad about the chumming strategy. Next is Pepe, who doesn’t really look like a “Pepe.” He’s a white-haired man with a linebacker’s frame whose shoulders and spent knees give him a swagger. He got his nickname as a football player because he was fast for a big man. His job is cutting bait and keeping the mood boisterous. Finally, there’s Barry, quiet and diligent as he moves about the boat checking everything and pitching in where needed.

Their personalities are as different as can be, but they each fell into and embraced their role on this big-game fishing boat, and now they’re as fluid as any sports team working together on a field of play. Brad cranked the music and the mood was upbeat.

Fish On!

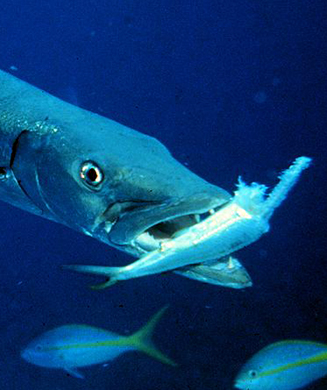

After an hour, one of the balloons bobbing on the blue rollers darts under the surface as a line tightens and a brass big-game reel starts to zing. The sound of the reel clicking off line launches everyone into action, though the ensuing fight is short. Kyle pumps the five-foot blue shark right in. Back out go the baits and the mood reverts to that of a party at which everyone is waiting for the guest of honor to show.

I ask Chris about big sharks. “Anyone can land a small blue,” he says as his fingers work a leader. “But a big mako takes experience.” He explains how he’ll bring it up alongside the boat and let it go if it’s under the tournament’s minimum of 200 pounds. But if it’s really big they might have to drag it to kill it.

As the ocean rolls us along miles out of sight of land, I ask how strong those big makos are. Chris smiles and says, “When they’re big we hook into the gunnel. It’s a serious thing. You don’t need this big boat to fish for sharks—you can do it in a much smaller boat—but this boat just makes it more comfortable.”

Anyone with any sense knows there isn’t a great white shark on the planet that can pull a boat as big as Quint’s “Orca” against its engines, but Chris has stories about makos wreaking havoc in a different way. “Makos jump,” he says. “I’ve had them land almost right on me.”

“Yeah, it can be invigorating,” Pepe says, laughing.

Of course, much of the suspense in the film version of Jaws is the result of the movie’s crew not being able to keep the mechanical shark working. Stephen Spielberg was forced to mostly suggest the monster’s presence, which, backed by composer John Williams’ score, resulted in the tension. When shark fishing, though, there is always suspense.

The chum line stretches behind the boat and our eyes blur from watching the balloons bob. Suddenly, our collective anticipation is busted wide open as a huge mako jumps in the chum line. His first jump is 30 yards out, but on his next jump he’s beyond the baits.

“He might be 800 pounds!” says Chris as he quickly lets out more line. After a few minutes he concedes that, “that shark knows what we’re about. But, damn, I’d like to get him hooked.” Another hour passes before a reel goes wild, a rod dips, and line shoots up out of swells, sending water spraying. Chris races to get the other lines in. This is a big shark.

But the excitement is over before it even has a chance to ramp up. The shark ran before the boat could turn and chase, and it busted off. Kyle is left shaking his head.

The day goes like that. Small makos and blues are hooked, Kyle muscles them in, and Chris lets them go without taking them from the ocean.

Back On Land

At the weigh-in, the crowd is bigger. Children sit on the pavement under the ropes and lick ice cream cones as they look up at the sharks being weighed. Spectators ooh and ahh and shoot photos with their cell phones. The scientists do their thing. The warm afternoon is wrapped in a stunning blue sky and the swanky town is hopping.

The “Magellan” returns from its day on the water. Capt. Greiner looks like a very satisfied man as the crane lifts another porbeagle from his boat. This one is 378 pounds. The audience applauds.

There still aren’t any protestors and most of the people in the crowd have found this monster shark weigh-in by chance. To them it’s interesting, eclectic, and American. Another boat with a 356-pound porbeagle ends up taking second place and a boat with a 265-pound thresher takes third. Some of the shark meat will go to a local soup kitchen.

Later, the dock is cleared of spectators and the captains and their crews come in for dinner and awards. Steve James’s uncle, Lloyd James, and aunt, Debbie, give heartfelt speeches about Steve and this tournament. The melancholy nature of this remembrance doesn’t dampen the mood, but gives it the depth and joy of an Irish wake, just as Steve would’ve wanted, everyone says.

In the end, shark fishing isn’t about the fish as much as it is about our search for the wild unknown. If the sportfishing line that connects sharks with humans is ever severed, we’ll lose something honest about ourselves—and that won’t be good for us or for the sharks.

After the tournament, I called Jerry Gibbs, Outdoor Life’s longtime Fishing Editor, to ask him about today’s shark-fishing culture. “Frank Mundus is dead, Peter Benchley [the author of Jaws] is dead and there’s been this whole turnaround in shark fishing as shark populations grow,” Gibbs told me. “You can’t kill a great white, a great hammerhead, and so on today. There’s been a huge push to view sharks not as monsters but as a natural participant in the scheme of things. And much of that push has helped stop shark finning in most places.

“That said, sharks still light an atavistic fire in us and there’s a sub-culture of hardcore guys who like to go one-on-one with them. There is a great future for shark sportfishing.” Just as Steve James would’ve wanted.