We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

A couple of years ago, curiosity got the better of me and I spent (read: wasted) an hour or two every day for a week scanning firearms chat rooms on the Internet. During that week I saw handloads recommended that would blow a cannon to smith-ereens, gunsmithing “tips” that would wreck an arsenal and assorted advice on firearms, scopes and ammunition that gave me the shivers.

All of this “advice” was contributed by self-styled experts cowering anonymously behind silly screen names; the anonymity, however, did nothing to conceal their ignorance. The one statement that stood above the rest for misguided stupidity was made by an individual who declared that he saw no reason to continue reading shooting magazines because he could learn all there was to know about guns and shooting right there in that chat room.

Had his face, rather than a phony screen name, been up there on my monitor, I might have tried to ram my fist through the glass and slap some sense into him, because that week, in the very chat room he was so highly praising, a remarkable new development in firearms design had just been thoroughly trashed.

The gun was Remington’s just announced Etronix rifle, and the dozens who condemned it had never shot one or seen one and hadn’t the vaguest notion of how one worked. Yet every criticism was applauded and cheered by onlookers in a mass pile-on, giving me a mental image of a cave full of primitive savages who have been shown a clock, with each trying to explain to the others what it is for and how it works and all of them finally beating it to death with their clubs. Only now the clubs were keyboards.

It’s no secret that the Etronix has had nowhere near the success Remington envisioned it would, but I’m not suggesting that a chat room full of airheads had the clout to tear it asunder. If anything, it was Remington that consigned the Etronix to its current moribund state. It’s a cautionary tale worth telling, but first let me tell you I’m biased, as you would have discovered anyway.

To be fair to the Web wackos, the manufacturing and marketing of electronically fired guns and cartridges does have a record of failure. Though the concept has been brilliantly successful in military rapid-fire weaponry, it has fizzled in sporting applications. But consider the human element.

Carmichel’s Concept

It is human nature to resist change, and we gun people, like the wannabes in the chat room or the savages beating the clock, are particularly fearful of ideas that represent change or things we don’t understand. This is silly, however, because the Etronix is easy to understand and the ammunition is as familiar as mom’s apple pie.

Back in 1985 I authored The Book of the Rifle. In it I wistfully described a simple ignition system in which the complexities, complications and un-reliabilities of traditional percussive ignition were eliminated and replaced with a simple circuit that would work somewhat like an ordinary electric dynamite cap. The advantages of such a firing system included virtually instant lock time (the interval between pulling the trigger and propellant ignition), simplicity, reliability and, presumably, reduced manufacturing costs. Otherwise, I foresaw no particular differences from ordinary rifles and ammo. Cartridges could be reloaded the usual way, except for using a different type of primer.

I don’t know if anyone at Remington read the book, but in any event I’ll take no credit, because the system I envisioned is so simple and obvious it would have been inevitable eventually, even in an industry that proceeds with the unerring swiftness of a crippled snail sleepwalking.

The Etronix Is Born

The Etronix project was one of the first and most expensive developments to come out of Remington’s spanking-new Kentucky research center. Not only did the electronics on these guns have to be designed d tested from scratch, but electronically activated primers had to be developed along with a way to mass-manufacture them. The primer has long been called the “spark plug” of a cartridge, and with the Etronix system that’s truer than ever.

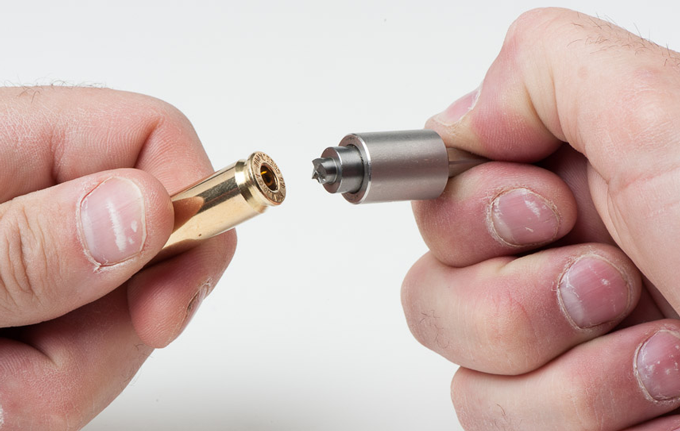

The Etronix primer can best be described as two electrical poles, one positive and one negative. When you press the trigger a circuit is completed and a spark plies between the primer’s two poles, like a car’s spark plug, exploding the priming mix.

It sounds simple, but Remington’s safety-conscious engineers went all out to prevent accidental discharges and ended up with a considerably more complicated system than I had envisioned. Virtually every conceivable cause of mishap-errant radio signals, power-line emissions, static electricity, water seepage-was considered, and safety barriers were built into the system. This is why one of the biggest laughs I had while tuned in to one of the Internet’s Etronix bashings was at some yahoo’s prediction that such a rifle might accidentally fire if struck by lightning. As if gun owners are normally inclined to venture out into lightning storms with gun in hand.

In 1999, the Etronix rifle was announced to the shooting public with the fanfare befitting a revolutionary concept, but Remington’s marketing strategy was more than a little obscure, as its executives now privately confess. [pagebreak] Marketing Mishaps

The plan was to introduce Etronix rifles on a limited basis, with an effort to get them mainly into the hands of more elite shooters. The rationale was that elite shooters would best recognize the advantages of the electronic system and would provide positive feedback and good word of mouth, as well as spot any trouble that needed correcting. Accordingly, the first Etronix rifles were built in heavy-barrel varmint configuration, in accurate varmint calibers. This turned out to be a huge marketing mistake for unanticipated reasons.

One of the main selling points of the Etronix system is practically instantaneous lock time. That’s a pretty big advantage when a rifle is in motion and the crosshairs are skittering across a target. Off-hand shooting with a lightweight hunting rifle is a good example of where lightning-fast lock time would shine. But heavy-barreled varmint rifles, like the first Etronix models, do not particularly benefit from quick lock time because they are typically fired from solid, unmoving positions such as benchrests. Thus the Etronix rifles were mostly used in conditions where their quick lock time offered little or no noticeable benefit.

Another failing of the Etronix rifles, besides their high price, was that they were fitted with production-grade barrels. In hindsight, it’s easy to see that they would have made a much better initial impression had they been fitted with Remington’s highly accurate 10-X barrels. A rifle’s accuracy is no better than its barrel, regardless of the firing system, so it was inevitable that Etronix rifles would deliver accuracy virtually identical to that of Remington’s standard varmint rifles, which cost hundreds of dollars less.

Accuracy at Last

Still, I was convinced that the Etronix should have had an accuracy edge, all other factors being equal, because of the nonmoving nature of the system. And since the barrel seemed to be the main hurdle to hairsplitting accuracy, I undertook a simple but ultimately very revealing test.

Starting with a new Etronix, I did a series of controlled accuracy tests with a variety of factory ammo and handloads. Half of each batch of ammo was saved for later testing. The rifle was then sent to Shilen Rifle Barrels, the famous makers of ultra-accurate, tournament-winning barrels, and the original Remington barrel was replaced with a top-of-the-line Shilen. The only stipulation I made was that the Shilen barrel be of the same length and diameter as the original so there would be no weight difference. Upon return of the Shilen-equipped Etronix, accuracy testing was repeated, firing the same batches of ammo used in the initial phase of the test series. From the first five-shot groups on, the improvement was little short of astonishing, with the accuracy potential of the Etronix being revealed at last. During test shooting of the rebarreled rifle by Remington personnel, one shooter exclaimed after his first five shots that it was the smallest group he had ever fired in many years of shooting. Another was so amazed at the performance that he suggested I might have somehow loaded the test ammo with “magic” bullets.

Whether this demonstration will encourage the powers at Remington to rescue the Etronix remains to be seen. To be sure, there are other improvements to be made, such as a quicker and easier way to change the nine-volt battery (which lasts about 250 shots on average). And I’m told the electronics have already been simplified and made more compact.

Anyway, as I said before, I’m biased, just as anyone would be who saw his pipe-dream prediction for a better ignition system become a reality. And as for the Internet nuts who took such perverse delight in bashing the Etronix, here’s something they might want to ponder: Let’s suppose that firearms had always been fired by electricity when suddenly a gunmaker decided to introduce a new ignition method in which a complicated series of levers and sears-all prone to breakage and disorder-released a spring-driven rod (which had to be reset with each firing) that smashes into an explosive chemical to ignite a flash of fire. Do I hear anyone say that it would be barely a step beyond starting fire by banging two rocks together? Or killing a clock with clubs?the original so there would be no weight difference. Upon return of the Shilen-equipped Etronix, accuracy testing was repeated, firing the same batches of ammo used in the initial phase of the test series. From the first five-shot groups on, the improvement was little short of astonishing, with the accuracy potential of the Etronix being revealed at last. During test shooting of the rebarreled rifle by Remington personnel, one shooter exclaimed after his first five shots that it was the smallest group he had ever fired in many years of shooting. Another was so amazed at the performance that he suggested I might have somehow loaded the test ammo with “magic” bullets.

Whether this demonstration will encourage the powers at Remington to rescue the Etronix remains to be seen. To be sure, there are other improvements to be made, such as a quicker and easier way to change the nine-volt battery (which lasts about 250 shots on average). And I’m told the electronics have already been simplified and made more compact.

Anyway, as I said before, I’m biased, just as anyone would be who saw his pipe-dream prediction for a better ignition system become a reality. And as for the Internet nuts who took such perverse delight in bashing the Etronix, here’s something they might want to ponder: Let’s suppose that firearms had always been fired by electricity when suddenly a gunmaker decided to introduce a new ignition method in which a complicated series of levers and sears-all prone to breakage and disorder-released a spring-driven rod (which had to be reset with each firing) that smashes into an explosive chemical to ignite a flash of fire. Do I hear anyone say that it would be barely a step beyond starting fire by banging two rocks together? Or killing a clock with clubs?