We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Let’s do the impossible—right now—by deciding on the very best bullet for your next big-game hunt. To set the scene, let’s say it’s the western hunt you’ve dreamed of for years, and it is only a month away. You have a glistening new rifle in .30/06 caliber and you’ve topped it off with the best scope money can buy. All that remains are a few practice sessions at the local shooting range and sighting-in your new ’06 so precisely that you’ll be dead on target when that big bull elk steps out of the timber.

So you stop by a gun shop for some ammo and sight-in sessions and the dealer hits you with a question you weren’t ready for: “What weight bullets do you want?”

“Oh, I dunno,” you stumble in response. “Whatever it takes for elk. The outfitter guiding me said the .30/06 would be a good all-purpose caliber for the elk, antelope and mule deer we’ll be hunting, but he didn’t say anything about bullets. Just gimme the best bullets you’ve got.”

“Look mister, all my bullets are good, but I got six different weights in .30/06, from 125-grain all the way to 220-grain, so name your poison.”

What the heck, elk are big critters, probably the heaviest bullet will be best.

Bigger is always better—or is it? “Bigger is best” was the military way of thinking just a little over a hundred years ago when the .30/40 cartridge was adopted as the official U.S. Army round. Before that, it had been the thunderous .45/70, which heaved a 405-grain slug. Thus with the “downsizing” from .45 to .30 caliber, a 220-grain bullet was decided on for the new round, and my guess is that many of the brass hats, some of whom were Civil War veterans, considered the little bullet downright puny and marginal for military purposes.

Such thinking was shattered by volleys of light-but-deadly bullets during our war with Spain, in which the fast-firing, flat-shooting 7mm Mauser bolt rifles were about the only thing Spanish troops had going for them. Veterans of that war long remembered the crack and whiz of the 173-grain Spanish bullets (the 700 Spanish defenders of San Juan hill inflicted twice their number in casualties), and the U.S. Military decided, at last, to catch up with the rest of the world in terms of small arms and ammo. That led to the development and adoption of the now legendary 1903 Springfield rifle and, in 1906, the .30/06 cartridge. (A “redheaded stepson” on the .30-caliber family tree known as the .30/03 was the army’s choice for three years preceding the .30/06. It too was loaded with 220-grain bullets, reflecting the maxim that old habits die hard.)

The new .30/06 military round was loaded with pointed 150-grain bullets (the earlier 220-grain slugs were round-nosed) loaded to a snappy 2,700 feet per second, and the world hasn’t been the same since. If you’re wondering what this slice of military history has to do with your elk hunt, the purpose is to give you some idea of how tradition affects even modern-day bullet selection. Like those one-legged Civil War veterans of a century ago who steadfastly maintained that heavier is better, there is a small (and growing smaller) army of hunters who stubbornly cling to the notion that a 220-grain bullet from their .30/06 shoots harder, busts brush better and kills deader than any lighter bullets ever will.

The truth is that most 220-grain bullets have very few redeeming features when loaded in the .30/06. To begin with, it starts out too slow (about 2,400 fps at the muzzle) and gets a lot slower in a hurry because the round nose doesn’t drill through the atmosphere as efficiently as a pointed bullet. Somewhere in dim history a rumor got started that round-nosed bullets penetrate brush better than the pointy types. Whoever thought up that one was in need of a cold shower, because round-nosed bullets with big patches of exposed lead at the tip—I call ’em ice cream cones—are about the worst possible choice for hunting in brus Picture a bowling ball made of putty and you’ll get the idea.

A few years back I got a call from a big ammo company asking if I could explain why they sold so much .30/06 ammo with 220-grain bullets in a two- or three-county area not far from where I live. I told him I had no idea, but when I checked it out I discovered that “shooting” fish was legal and popular in a river that ran through those counties. Apparently the locals felt that the heavier bullets created more fish-stunning concussion and, if so, the old 220-grain slug has a redeeming quality after all.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against heavy bullets. For example, of the various bullets I load in my .338 Win. Mag., I stoutly maintain that a 250-grain-the heaviest bullet commonly available-is by far the best choice. After all, that’s what the .338 Mag. is all about. Anyone who favors lighter slugs just hasn’t been eye-to-eye with a grizzly.

What WorksSAnd Why

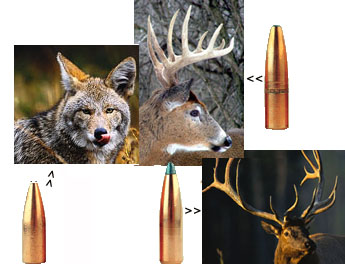

What I’m getting at is that every caliber has a rather narrow range of bullet weights within which it delivers optimum performance. That fact brings us back to your .30/06 and the upcoming hunt for elk, mule deer and pronghorns. Realistically, the “working range” of bullet weights for the ’06 is 150 to 180 grains, and there is no shortage of makes and styles of bullets in this weight group, as you’ll see by thumbing through ammo-makers’ catalogs. A ballistic hair-splitter might try to convince you that you need 150-grain loads for pronghorns and deer and 180s for elk, the logic being that the faster, flatter-shooting 150-grain bullet will serve you best for long shots at pronghorns, whereas the heavier bullet has the extra punch and penetration you want for elk. If such advice sounds profound in the gun shop, out in the real world the bitter fact of the matter is that rifles seldom send different bullet weights to the same point of impact without changing the sight setting. In other words, if your rifle is sighted-in with 180-grain bullets, 150-grain loads may hit a few-or even several-inches off aim. So keep it simple and stick with one bullet weight.

How about compromising halfway between 150 and 180 with a 165-grain bullet? Is that a good idea or would such a trade-off mean you’ll be hunting with a bullet too slow for pronghorns and too light for elk?

Take another look at ammo catalogs and the numbers will surprise you. Loadings for the ’06 with 165-grain bullets are rather recent, and when first introduced were hailed as a surefire way to “magnumize” the plodding octogenarian. How so? The formula for the magnum-like performance of these new ’06 loads was not because of anything magical about the number 165 but, rather, because the relatively new 165-grainers were the beneficiaries of advanced ballistic design. To give you a clear picture of how the shape of a bullet can dramatically affect its performance, take a look at the .30/06 ballistic figures taken from Remington’s catalog (below). Even though the energy level for all four bullets is about the same at the muzzle, the 165-grain bullet has gained a significant lead at 300 yards and the gap grows even wider as distance increases. Not only that, but it shoots as flat as the faster-starting 150-grain Bronze Point.

How Bullets Shape Up

How can it be that the 165-grain bullet is 110 fps slower than the 150-grain bullet at the muzzle but can catch up and pass it before they’ve traveled 300 yards and at the same time deliver more downrange punch than the heavier bullet? This neat trick of ballistic sleight of hand is pulled off simply by giving the 165-grain bullet a more streamlined shape so it doesn’t lose speed as rapidly as less advanced shapes. By maintaining velocity more efficiently, the streamlined bullet has a flatter trajectory and is more resistant to crosswinds, both of which improve your chance of making a well-placed hit at longer yardage.

So here is where we begin to realize that the shape of a bullet can be as important as its weight, sometimes even more so. Not that I expect that there will be a lessening of arguments over which bullet weights are best for any particular caliber; however, by adding the shape factor to such debates a whole new understanding of bullet performance may emerge. But how can you be sure which bullets have the most efficient shapes? If you compare a pointy-tip bullet to a round- or flat-nosed design it’s easy to see which will penetrate the atmosphere more efficiently and thus maintain more downrange knockdown punch. Also, if the ammo box says the cartridges are loaded with boat-tail bullets, it’s a safe bet that they have better-than-average aerodynamic efficiency. However, the best guides for comparing bullet weight versus downrange performance, as well as one brand against another, are the ammo-makers’ catalogs. These are free and available at most gun shops and contain a tremendous amount of ballistic information about each caliber and bullet weight.

Take a look at the bullets available for the .270 Win., .280 Rem., 7mm Rem. Mag. and .300 Win. Mag. and compare them on the downrange performance charts and you’ll be amazed by some of the differences.