We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

If ever a cartridge was born with an albatross dangling from its neck, it was the .280 Remington. In today’s shooting market, any new cartridge, be it good, indifferent or awful, is assured a slavering Pavlovian response from gun writers and the publications in which their bylines reside. But back in 1957, when the .280 first saw light, there were fewer gun magazines and no television shows vying, as they do now, to out-yodel each other for advertiser dollars. Gun writers tended to be even more ornery than they are now and were generally inclined to treat the .280 as something that would go away if ignored. Mention of the cartridge, when it was referenced at all, tended to fall into the “so what?” or “why did they do that?” category of breaking news.

Bad Rumors

The reason shooting soothsayers of that rustic era were asking “why?” was because the new .280 Remington was wedged between two of the most popular big-game calibers of all time: the .270 Winchester and the .30/06. Did the .280 have something to offer that these immensely popular calibers did not? A comparison of ballistic tables certainly doesn’t indicate that the .280 had any special magic. Its listed velocity for a 150-grain bullet was 2,810 feet per second, a not-exactly-breathtaking 10 fps faster than the .270 with same weight bullet, and a fairly significant 160 fps slower than the .30/06 with 150-grain factory loading.

As it happened, about the time of the .280’s introduction I’d discovered that I could get away with reading gun magazines in my high school classes simply by encasing them in a large notebook and gripping a pencil as if I was diligently taking notes. Thus while Miss Crookshanks waxed romantic about Shelley or Keats, I could immerse myself in the wisdom of an O’Connor or Page. This pursuit made no contribution whatsoever to my grades but it somewhat prepared me for the hardscrabble years that were to follow.

According to what I learned during those classroom studies, the .280 was on the fast road to wherever it is that cartridges go when they die young. In my own innocent judgment it was a wallflower that lacked the glamour of the much-touted .270 or the purposeful dignity of the .30/06, which is to say it never made the Top 20 list of rifles I planned to own when fortune came my way. Similar conclusions were reached by legions of hunters and shooters everywhere. The .280’s prospects were further reduced when word got around that Remington purposely “loaded it down” so the gun could be safely chambered for its recently introduced Model 740 autoloading rifle. This curse dogged the .280 for years and is occasionally repeated even today.

Several years ago I became intrigued by this chapter in the .280’s history and checked out the “loaded down” rumor with a few of the older heads at Remington. As with many rumors from the shooting industry, there’s a grain of truth to this one, but the real facts I gleaned tell us a lot more.

[pagebreak]Unlike earlier autoloaders such as Remington’s M81, which were limited to mild cartridges such as the .30 and .35 Remington, the M740, which was introduced in 1955, was designed for rip-snorting calibers such as the .30/06. It was a successful rifle and would have been even more so had it been chambered for the .270 Winchester, but it wasn’t. And the word going around at the time was that the M740 couldn’t handle the 270’s pressures. And here’s where the strange saga of the .280 gets particularly interesting.

Not counting some of Remington’s interoffice politics, personal opinions and jealousies regarding the .270 during the 1950s, I learned that the M740 and .270 actually did not make a good match. Not necessarily because of the .270’s high pressures, but because the M740 tended to be finicky about what it was fed, its gas-operated system being reliable only when adjusted to rather specific pressure levels.

The .270 loads of the day, I was told, tded to develop varying pressure levels, which in turn could have resulted in the M740’s erratic operation. Thus the .280 was not so much “loaded down” as loaded to specific pressures compatible with the M740. Apparently, it isn’t often noticed that the M740 was also chambered for Remington’s new .244, a hot round that, like the .270, generated pressures over 50,000 PSI. In 1960, when the M742 replaced the M740, it too was catalogued sans the .270.

A Handloader’s Dream

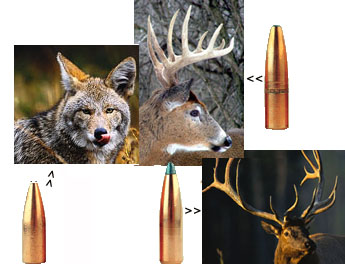

Just as the future of the .280 seemed at its bleakest, a variety of forces were galloping to its rescue, one being an army of handloaders. The heart and soul of handloading rifle ammo is making a good thing better. And it didn’t take long for handloaders to discover that the .280 was a Cinderella waiting to be taken to their ball. By increasing pressures only moderately, velocities increased dramatically. Better yet, bullet makers even then offered a particularly tempting variety of 7mm bullets ranging from 100 to 175 grains. By picking the right bullet for the job, a handloader could hunt everything from woodchucks to moose with his .280.

Some handloaders were so ecstatic about the performance they got from the .280 that they were proclaiming it a ballistic miracle. Such claims were reinforced when DuPont published loading data that indicated that with the same bullet weights and propellant charges, the .280 delivered velocities equal to the .270 but at thousands of pounds less pressure! So it seemed the .280 had some magic after all, and has always remained a favorite with handloaders for this and other reasons. When Winchester began loading the .280, one of its technicians told me it was among the least temperamental calibers they had ever loaded.

Another big boost for the .280 was a wake-up call from hunters to Remington that the grand era of bolt-action rifles had arrived and they’d better get with the program. Remington’s bolt rifles of the time, the M721 and shorter-action M722, were strong and accurate but about as sexy as a roadkill possum, especially when compared to Winchester’s stylish and popular M70 bolt rifle.

[pagebreak]Seeing the writing on the wall, Remington responded in 1958 with the M725, a rifle far more handsome than the M721 and initially chambered for the .280 as well as the .270 and 30/06. This was a major breakthrough for the .280. Although it had been offered in the old 721, its union with the 725 (along with the ’06 and .270), cast it in a new and more flattering light, more of a cartridge to be reckoned with. Manufactured for only about four years, M725’s are now much sought after by collectors. Particularly in demand is the .280, which is considered a classic union of rifle and cartridge.

Name Changes

This sudden glamorization of the .280 was not lost on the potentates at Remington, who now realized there was life for the caliber well beyond the limitations imposed by autoloading rifles. Something that would give the .280 a new lease on life, they reckoned, was to glamorize it with a new name. Just calling it the .280 sounded so, well, ordinary. After all, it was a 7mm, so why not give it some continental pizzazz by calling it the 7mm/06? This made pretty good merchandising sense because Remington had already done well for itself by adapting two popular wildcats: the .22-250 and .22/05. So why not a 7mm/06? It was also a legitimate claim because wildcatters had, in fact, been necking .30/06 cases down to 7mm for decades.

Accordingly, there was a run of M700 rifles and ammo marked 7mm/06. Problem was, the .280 wasn’t a true 7mm/06. During its development the shoulder length had been increased by about five hundredths of an inch as a safety measure so it couldn’t be fired in .270-caliber rifles. But now, if an unsuspecting handloader fired necked-down ’06 cases in Remington’s rifle, there’d be a potentially dangerous headspace situation. So the 7mm/06 name was quickly discontinued and the rifles and ammo were recalled. Some rounds are still in circulation, however-and are considered genuine collector’s items.

Still determined that the .280 needed a more glamorous name, Remington rechristened it the 7mm Express. This has a pretty nice ring to it, but again there were unintended consequences. The 7mm Express tended to get confused with Remington’s 7mm Magnum, another potentially dangerous situation. So the folks at Remington gave up on the name change and the .280 has been that ever since.

Coming of Age

Such misguided name-change shenanigans would have caused a meltdown for a lesser cartridge, but by then the .280 had earned a loyal following of dedicated fans. I have used the .280 handloaded with 160-grain Grand Slams on a couple of elk and an African bongo, but my go-to load has always been the 140-grain Nosler Partition, which works just as well on elk as the heavier bullet. And the flatter trajectory of my rather warm handloads make it a better choice for smaller game, such as sheep.

[pagebreak]When Melvin Forbes announced his revolutionary line of Ultra Light bolt rifles back in the 1980s, I was one of his first customers. My old .280, which had been built around a pre-1964 Model 70 action by ace stock maker Clayton Nelson, had suffered much use and abuse through the years and deserved an honorable retirement.

The .280 rifle Melvin delivered weighs in at a bit less than 7 pounds with scope and has been my most-used hunting rifle in recent years, especially on hunts where I anticipated hard hiking and rough weather.

When Remington introduced its lightweight M700 Mountain rifle back in the early 1990s it was initially offered in .280, along with the .30/06 and .270. Rifles in the .280 chambering outsold the other two combined. So at last the .280 had overcome its dismal beginnings and joined the pantheon of great hunting cartridges.

Is the .280 my favorite hunting caliber? When I look back over my many hunts I’d have to say it is, if only in terms of success and good service. But I’ve also been in this business far too long to make outrageous claims about any caliber being significantly superior to others. That may make a few readers happy but rankles a lot more, especially when making the inevitable comparison of the .280 with the .270 and ’06. So I’ll put it this way: When I get mail from readers asking me to help them decide between a new .270 and a new .30/06, I politely suggest that they also consider the .280. I’ve had lots of them write back, thanking me for opening their eyes to a truly superb caliber.

For a complete list of factory loadings for the .280 Click Here discontinued and the rifles and ammo were recalled. Some rounds are still in circulation, however-and are considered genuine collector’s items.

Still determined that the .280 needed a more glamorous name, Remington rechristened it the 7mm Express. This has a pretty nice ring to it, but again there were unintended consequences. The 7mm Express tended to get confused with Remington’s 7mm Magnum, another potentially dangerous situation. So the folks at Remington gave up on the name change and the .280 has been that ever since.

Coming of Age

Such misguided name-change shenanigans would have caused a meltdown for a lesser cartridge, but by then the .280 had earned a loyal following of dedicated fans. I have used the .280 handloaded with 160-grain Grand Slams on a couple of elk and an African bongo, but my go-to load has always been the 140-grain Nosler Partition, which works just as well on elk as the heavier bullet. And the flatter trajectory of my rather warm handloads make it a better choice for smaller game, such as sheep.

[pagebreak]When Melvin Forbes announced his revolutionary line of Ultra Light bolt rifles back in the 1980s, I was one of his first customers. My old .280, which had been built around a pre-1964 Model 70 action by ace stock maker Clayton Nelson, had suffered much use and abuse through the years and deserved an honorable retirement.

The .280 rifle Melvin delivered weighs in at a bit less than 7 pounds with scope and has been my most-used hunting rifle in recent years, especially on hunts where I anticipated hard hiking and rough weather.

When Remington introduced its lightweight M700 Mountain rifle back in the early 1990s it was initially offered in .280, along with the .30/06 and .270. Rifles in the .280 chambering outsold the other two combined. So at last the .280 had overcome its dismal beginnings and joined the pantheon of great hunting cartridges.

Is the .280 my favorite hunting caliber? When I look back over my many hunts I’d have to say it is, if only in terms of success and good service. But I’ve also been in this business far too long to make outrageous claims about any caliber being significantly superior to others. That may make a few readers happy but rankles a lot more, especially when making the inevitable comparison of the .280 with the .270 and ’06. So I’ll put it this way: When I get mail from readers asking me to help them decide between a new .270 and a new .30/06, I politely suggest that they also consider the .280. I’ve had lots of them write back, thanking me for opening their eyes to a truly superb caliber.

For a complete list of factory loadings for the .280 Click Here