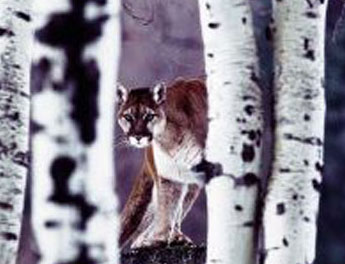

A cougar turned up in downtown Omaha. How it got there is anybody’s guess. A cougar was killed by a car in Indiana. Must have been an escaped pet, authorities said. A train hit a cougar in Illinois. It had a stomach full of deer meat. An Iowa farmer shot a cougar prowling around his soybeans. Unlike most pets, it had all its claws and teeth. A deer hunter in Arkansas found a picture of a cougar on his trail camera. Just 10 miles from Minneapolis, another trail camera photographed a cougar eating a deer. A DNA analysis of scat samples found in Michigan determined they were from cougar.

Reports like these led to the formation of the Eastern Cougar Network (ECN) in 2002. The ECN maintains a database of cougars that turn up where cougars-otherwise known as pumas, mountain lions and catamounts-are not thought to be. ECN members have been compared to UFO believers. But they have some reputable people on their scientific advisory panel and conclusive evidence to back up claims.

Sergeant Tangel is not alone. There have been cougar sightings in every Eastern state. “The cougar is the Bigfoot of the East,” says Mark Dowling, cofounder of the ECN. “We don’t trust sightings. We’ve had calls from Canada, Europe and every state in the U.S. from people reporting that they’ve seen a cougar. Some have even sent us photos of large house cats and golden retrievers. As a result, we only take hard evidence seriously-road kills, DNA evidence….”

The thing is, there’s a lot of hard evidence (see map, next page). From East Texas north and east through Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, Indiana and Minnesota, hard evidence has been found where cougars were shot out more than a century ago. Let’s start in Kansas, where until last year cougars hadn’t been officially documented since 1904. The Kansas Biological Survey tested scat samples found on the Kansas University campus. The DNA analysis was conclusive. “There’s no doubt the scat samples are cougar,” says Mark Jakubauskas, research assistant professor with the Kansas Biological Survey.

Just north in Nebraska, John Hobbs, state director of Wildlife Services (the segment of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that responds to wildlife problems) says, “Six years ago there was a debate over whether we even had cougars in the state. The debate is finished. Cougars have moved through the river valleys right across the state.”

Which could explain how a farmer in Ireton, Iowa, happened to shoot and kill a cougar last year. And farther north, how a Grand Forks County deputy sheriff happened to videotape a cougar near the Iowa-Minnesota border. And how Rich Staffon, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources wildlife manager for the Duluth-Cloquet area, came to say, “We’re fairly confident there is a wild population [BRACKET “of cougars”] out there.”

But it’s farther east, in Michigan, where the debate over whether the cats are residents has gotten really contentious. In February 1997, just south of Mesick, Christi Hillaker caught a cougar on videotape as it walked through her yard. Since then, the number of sightings has soared and two people say they have snapped photos of cougars in the state. Meanwhile, Mike Zuidema, a retired state forester, earned the nickname “Crazy Mike” from his coworkers after he claimed to have seen a cougar. Zuidema has since interviewed 700 people who say they’ve spotted cougars in Michigan. He’s even convinced the Michigan Wildlife Conservancy (MWC) that he’s on to something.

[pagebreak] The MWC now says it has seven scat samples that DNA analysis has proven to be from cougars living in both the Upper Peninsula and in lower Michigan; the conservancy thinks it’s a population that staved off extirpation thanks to efforts by sportsmen’s clubs to preserve land and to restore deer populations. Others, including the Michigan DNR and the ECN, are skeptical. However, Brad Swanson, assistant professor obiology at Central Michigan University (where the scat was analyzed), says, “The DNA tests were conclusive. Seven of the scat samples are from cougars.”

Two Michigan newspapers-The Traverse City Record Eagle and The Bay City Times-have asked the state to acknowledge that the alleged cougar population exists. Brad Wurfel, the press secretary for the Michigan DNR, says the agency will continue investigating but doesn’t have any hard evidence yet. The DNR has not reviewed the DNA test results. Dennis Fijalkowski, executive director of the MWC, says, “The state’s not investigating anything. They want this to go away.”

A similar, though so far less entrenched, debate is beginning in New York. Peter V. O’Shea Jr., a former New York City police sergeant, has become a one-man clearinghouse for cougar sightings in New York’s Adirondacks. Some police officers even refer excited callers to O’Shea rather than to the state Department of Environmental Conservation. O’Shea believes the state of New York won’t admit there are cougars in the Adirondacks because cougars are listed as an endangered species in the East. If their presence becomes official, by law the state has to begin studies and do environmental-impact statements, which will pit environmentalists against land owners. In other words, O’Shea believes, it’s all about money-an argument that O’Shea’s fellow mavericks in Ohio, New Jersey and elsewhere use to explain skepticism from state game departments.

Before we become entangled in this debate, let’s step out of the wacky world of cougar confirmations and into the misguided world of cougar control in California. If cougars are moving east, the West’s increase of problems near urban areas could foretell what might happen in the rest of the country.

Welcome to the land that banished houndsmen. That banished common sense. That sent science and responsible game management packing. Welcome to California.

[pagebreak] Take a look around. Proposition 117, a voter initiative passed in 1990, ended lions’ classification as “game mammals,” banning all cougar hunting. (The state had halted the season in 1972.) Since then, complaints about cougars have skyrocketed. While only 10 cougar attacks were reported from 1890 to 1990 in all of North America, that number has been exceeded in just the past 14 years. Since 1890, the state of California has verified a total of 14 attacks on humans by mountain lions; nine of those attacks have taken place since the ban on cougar hunting.

But you can’t believe those numbers. Just a cursory review of databases and publications-Cougar, by Harold P. Danz (Swallow Press, 1999); Cougar Attacks, by Kathy Etling (The Lyons Press, 2001); and “Mountain Lion Attacks on People in the U.S. and Canada,” located at www.tchester.

org/sgm/lists/lion_attacks.html-shows discrepancies, attacks listed in one source but not another. There are many reasons for this. States often don’t share reports, and some are better about keeping records than others. Incidents that don’t lead to attacks are often not registered. Organizations that maintain databases often have political agendas. Wildlife Services keeps records of livestock loss, but not attacks on humans. According to Doug Updike, the California Department of Fish and Game’s senior wildlife biologist, “An attack doesn’t become official until it meets certain criteria.” Perhaps someone should tell that to Allyn Atadero, whose child was taken.

In all fairness, though, cougars have always been hard to figure. President Theodore Roosevelt called the cougar “the lord of stealthy murder” for a reason. Cougars hunt by night and hide by day, which makes them awfully hard to count. As a result, even though the California Fish and Game Department says there are between 4,000 and 6,000 cougars in the state, it can’t back up those numbers-nor can any other state with cougar populations. Game managers in much of the West make estimates based on harvest reports. In California, there’s no such indicator.

Though it’s unclear what the population numbers might be, it’s clear that California is saturated with cougars, says Lieutenant Bob Turner, a warden for 30 years with the California Game and Fish Department. The result, agree scientists, is that when kittens reach 18 months and their mothers evict them from their protection, the young females look for nearby territories, but the young males have to run for their lives because the dominant male will kill them on sight. So they move far-often right into suburbia. In California, these young (unhunted) cats have no real fear of people, so pets disappear and finally a cougar attacks a human.

[pagebreak] Despite these conflicts, in California game managers have to wait for a cougar to threaten a human before a tag can be issued. Still, an average of 100 “problem” cougars are now killed each year in California, which is about twice the number that were killed annually by hunters before cougar hunting ended in 1972.

Some groups, such as the Defenders of Wildlife, argue hunters can’t control cougar populations. This is hard to accept when you realize that over-hunting nearly wiped out cougars in the last century. In fact, Utah, Wyoming and other Western states already use hunting to balance cougar populations against human safety. Hunting works because hunters target the big toms-the same animals that make the immature cougars head for suburbia. Most Western game departments have broken up their states into management units. A quota is established annually for each unit. When the number of kills is reached in a unit, its season ends.

Mike Bodenchuk, head of Utah’s division of Wildlife Services, and his team of trappers respond to human-cougar conflicts in the state. “Hunted lions are well-behaved lions,” he says. “There always will be problems. But these conflicts can be minimized with sound management practices.”

However, some people feel that it’s our fault for taking the cougars’ habitat. For example, according to the Associated Press, just after a cougar killed a person in California this year, local resident Karin Malinowski said, “I hate to see people die like that…but I feel really bad for the mountain lion that was killed. We’re encroaching on their territory. What are they supposed to do?”

One has to wonder how much land is enough to ease those kinds of guilty consciences. According to the National Wilderness Institute, 39.8 percent of the United States (and 52.1 percent of California) has already been cordoned off for the wild. Also, the same voter initiative that banned cougar hunting in California set up a trust fund of $30 million a year for 30 years for state purchases of “cougar habitat.” After all, cougar populationons. Game managers in much of the West make estimates based on harvest reports. In California, there’s no such indicator.

Though it’s unclear what the population numbers might be, it’s clear that California is saturated with cougars, says Lieutenant Bob Turner, a warden for 30 years with the California Game and Fish Department. The result, agree scientists, is that when kittens reach 18 months and their mothers evict them from their protection, the young females look for nearby territories, but the young males have to run for their lives because the dominant male will kill them on sight. So they move far-often right into suburbia. In California, these young (unhunted) cats have no real fear of people, so pets disappear and finally a cougar attacks a human.

[pagebreak] Despite these conflicts, in California game managers have to wait for a cougar to threaten a human before a tag can be issued. Still, an average of 100 “problem” cougars are now killed each year in California, which is about twice the number that were killed annually by hunters before cougar hunting ended in 1972.

Some groups, such as the Defenders of Wildlife, argue hunters can’t control cougar populations. This is hard to accept when you realize that over-hunting nearly wiped out cougars in the last century. In fact, Utah, Wyoming and other Western states already use hunting to balance cougar populations against human safety. Hunting works because hunters target the big toms-the same animals that make the immature cougars head for suburbia. Most Western game departments have broken up their states into management units. A quota is established annually for each unit. When the number of kills is reached in a unit, its season ends.

Mike Bodenchuk, head of Utah’s division of Wildlife Services, and his team of trappers respond to human-cougar conflicts in the state. “Hunted lions are well-behaved lions,” he says. “There always will be problems. But these conflicts can be minimized with sound management practices.”

However, some people feel that it’s our fault for taking the cougars’ habitat. For example, according to the Associated Press, just after a cougar killed a person in California this year, local resident Karin Malinowski said, “I hate to see people die like that…but I feel really bad for the mountain lion that was killed. We’re encroaching on their territory. What are they supposed to do?”

One has to wonder how much land is enough to ease those kinds of guilty consciences. According to the National Wilderness Institute, 39.8 percent of the United States (and 52.1 percent of California) has already been cordoned off for the wild. Also, the same voter initiative that banned cougar hunting in California set up a trust fund of $30 million a year for 30 years for state purchases of “cougar habitat.” After all, cougar population