James Marlowe can’t stop laughing at our Avery duck decoys. I don’t think they’re particularly hilarious, and neither does Chris Jennings, who schlepped them 3,000 miles from Nashville, Tenn., to Marlowe’s village in interior Northwest Territories, Canada. But every time Marlowe looks at the wigeon, scoter, and scaup decoys spread on the floor of his house, along with our other waterfowl hunting gear, he cracks up.

“What’s with the toy ducks?” he finally asks. Jennings, who works for Ducks Unlimited, patiently explains that we’ll line the decoys out in the water just off the point in a lake where we hunters will be waiting to shoot real ducks that are attracted by the floating fakes.

Marlowe understands, but he shakes his head.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE PHOTOS FROM THE TRIP

“We don’t use decoys,” he says, suddenly serious. Marlowe is one of the most experienced hunters in his village of Lutselk’e, a First Nations community on the eastern shore of Great Slave Lake. “The only duck we hunt in the fall is the scoter because they’re so fat they can hardly fly. Everybody shoots a couple of scoters and freezes them whole, so if you run out of food in the winter, you always have a duck. The stringy ducks? We only shoot them in the spring, when they’re juicy. We get them in the puddles just off the road.”

As it dawns on me that he’s probably picking off nesting hens, I also realize that the sort of hunting that Marlowe does is vastly different from the sort of hunting that I do. As seriously as I take it, I hunt for fun, and follow a complicated set of rules, limits, and seasons. Marlowe isn’t bound by any of those constraints; he hunts to feed his people.

CHANGE ON THE WIND

The following afternoon, after he watches us shoot fat scoters and stringy scaup over those “toy” decoys, Marlowe hunches over a wood-burning stove and drops floured fillets of lake trout into sizzling oil. A yellow birch leaf flutters into the pan, and Marlowe flips it out before stuffing more twigs onto the fire and moving around the stove—a rusty 55-gallon oil drum turned on its side and snugged in the shoreline sand of Duhamel Lake—to tend a simmering pot. Inside, a meaty moose rib floats in foamy gray water.

When the moose is cooked through, Marlowe plucks it from the broth and places the rib on a grate over the flame to brown, nudging it next to the singed carcass of a duck that Jennings killed hours earlier. Marlowe turns the trout fillets. Then he pulls a putty-colored tube of meat from his cooler, sniffs it, pinches a hair or two from its glistening surface, and lays it on the grate next to the moose. It’s a tenderloin from the last caribou Marlowe shot, about six months earlier and nearly 50 miles to the east of here.

Satisfied with the progress of his meal, Marlowe leans back in his lawn chair and studies the sky. The wind, to his surprise, is out of the east, and delivers more golden birch leaves to his alfresco range.

“Tomorrow, we might get more ducks,” he pronounces. “Or snow. We’ll eat when the caribou is done.”

James Marlowe is a 40-something First Nations man. He speaks excellent English, but with a lilting, musical cadence to his speech. His first language is Athabascan, the tongue of his ancestors, members of the Akatcho band of the Dene. Marlowe (his surname is an Anglicized version of “Marlu”) has a broad, friendly face and wears blue jeans, black high-top sneakers, and a camouflage jacket with the label still on the sleeve. He was born in Lutselk’e—which means “place of the cisco” in Athabascan—just over the ridge from Duhamel Lake, where we are about to tuck in to this carnivore’s feast. Marlowe calls it “country food,” as in: It’s all from the country we are in right now, the eastern drainage of Great Slave Lake, the immense body of water that defines much of Canada’s Northwest Territories.

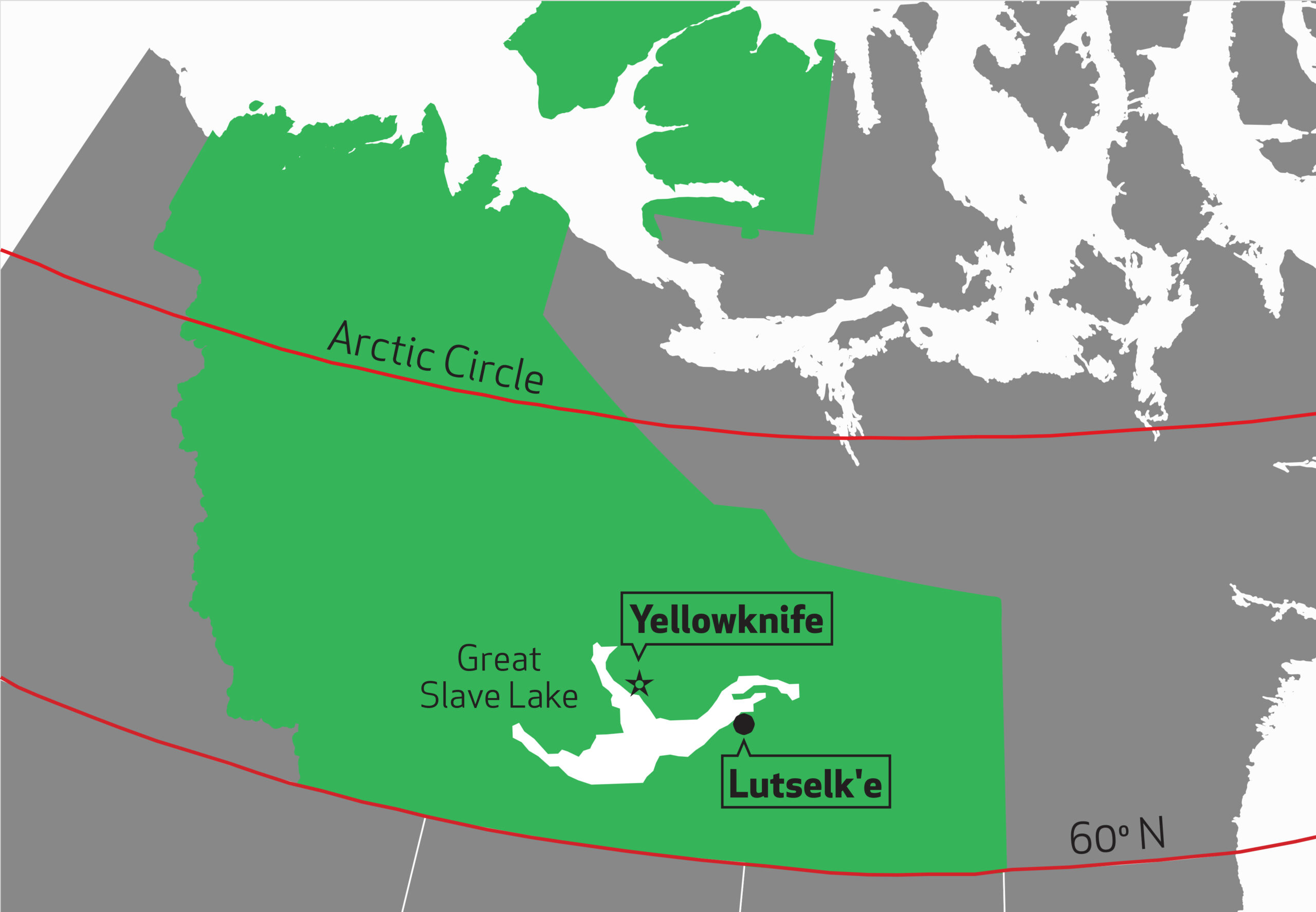

This is one of the most remote places on Earth. You can get here only by dogsled (as Marlowe’s ancestors did), by propeller aircraft (as I did), by motorboat, or by the once-a-year barge that brings pickups, television sets, sofas, building supplies, and fuel oil to the 300 or so inhabitants of Lutselk’e. In the winter, you can get here by snowmobile across the frozen lake. But even here, 125 miles from the nearest paved road, located in the provincial capital of Yellowknife, there’s more than snow and ducks in the air. Change is blowing in, too, and from every direction.

To the north, a constellation of diamond mines is proposed to be carved out of the stunted-birch forest. To the south, Alberta’s industrial tar-sand energy extraction zone is grinding toward Hay River, a main tributary of Great Slave Lake. To the west, the fastest-growing business sector in Yellowknife is hosting conjugal visits by Asian honeymooners, who fly from Tokyo and Beijing to this permafrost outpost to consummate their marriage under the northern lights in the belief that it will bring good luck, and baby boys, to their union.

My presence here also represents change to a culture that depends on trout and caribou for their prosperity. I’m here as a sort of experiment, a test to see if subsistence hunters like James Marlowe can make a living as commercial hunting and fishing guides, leading visitors from the south to their own “country food.”

SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

The land around Great Slave Lake is called the boreal forest, but it’s hard to think of this as a woodland. While a bristle of scraggly fir and birch trees covers the rocks, the dominant landform is water—frozen for more than half the year—a galaxy of small pothole ponds and long finger lakes that spreads in every direction away from the granddaddy of them all: Great Slave. The native humans of this place, the various clans of the Dene, survived here for hundreds of years on the animals and plants that evolved in this frosty biome stretching roughly between latitudes of 50 to 70 degrees north. The boreal, sometimes called the “taiga,” defines most of northern Canada, Scandinavia, and Russia.

“Ever been north of 60?” asked one of my companions on this trip, wetlands ecologist Gary Stewart, as we flew from Edmonton to Yellowknife. He was asking about 60 degrees of latitude, the universally accepted gateway to the North. “It’s different north of 60.”

Stewart, along with Jennings and Fritz Reid of Ducks Unlimited, asked me to fly to Lutselk’e (latitude 62.24 degrees north) with them to hunt ducks in one of the largest and most intact waterfowl habitats on earth. They also aimed to see how local Dene hunters might transition from hunting to feed their families and neighbors to guiding visitors who hunt for sport.

It’s part of a larger plan to bring sustainable economic development to the Dene. Tribal leaders recognize the change that’s closing in on their pristine homelands. While the idea of fat paychecks from diamond mining is appealing, the mines that operate in the Territories have fractured the fragile habitat, interrupted caribou migrations, and created divisive income gaps in traditional communities.

Tribal leaders are looking instead for an activity that can bring income but allow members to stay in their remote communities and engage in work that meshes with their sustainable land ethic. Their answer: ecotourism. In the summer, the Dene hope to run campgrounds and work as rangers in a huge tribal park along the north shore of Great Slave. And in the fall and winter, they hope to guide visiting hunters to moose, caribou, trophy lake trout, and ducks.

Ducks Unlimited is encouraging this sustainability model through its Boreal Initiative for a fundamental reason: If an intact, functional homeland for First Nations members can be conserved, so, too, can intact, functional habitats for native animals, such as the millions of waterfowl hatched each year in Canada’s northern forest.

My companions and I are the first of what the tribe expects to be a march of hunters from south of 60, and this intersection of sport and subsistence hunting comes with plenty of head-scratching curiosities.

GET THE NET

Fishing the trophy lake trout of Great Slave Lake has been on my list for years, so along with my shotgun and waterfowl camo, I brought a stout rod and plenty of heavy jigging lures to Lutselk’e. When I mention to Marlowe that I’m interested in the lake’s fish, he shrugs.

“We’ll get fish,” he says, a little unenthusiastically. Before long, we are puttering around the big lake in Marlowe’s fiberglass boat. The lake is so immense, and its points and bays so same-looking, that I wondered where we’d start. But Marlowe is decisive. We motor to a rocky point across the bay from town, where two orange floats bob in the water 100 yards offshore.

“We’ll fish here,” he says. So we do, casting and jigging around the orange floats. After several fishless minutes, I ask Marlowe why he picked this spot. The floats identify a gill net, he says, set to snare fish swimming past the rocky point.

“When someone in town wants fish, we come out to the net and get some,” he says. I look down at the puny lure hanging off my rod, and then at the vast lake, and I understand the locals’ wisdom, and the efficiency of their style of fishing.

As we boat around the lake, looking for more fishy points—and to our guide’s surprise, hooking a few meaty lakers for the frying pan—Marlowe asks me a question that reveals both the reach and limitations of his understanding of the world beyond Lutselk’e. I have been surprised at the degree of modernity in this remote place. Every house has electricity, multiple televisions, modern appliances, and even wifi. There are dozens of four-wheelers and pickups that villagers drive on the few miles of gravel roads around town. Most of these goods come on the once-yearly barge, which also delivers non-perishable goods to the only business in town, a combination grocery-hardware store, and anything else too big to fit in a plane or on a snowmobile.

During the long winters, the town’s hunters watch a lot of televised hunting shows from the U.S., Marlowe says. From satellite TV, he’s familiar with celebrity hunters and with hunting techniques for animals he’s never seen: wild turkeys, whitetail deer, feral hogs. But Marlowe has a question that had nagged him for years, and finally he has a visitor to ask.

“Why is it,” he asks, “that I never see Lee and Tiffany skinning their deer?”

BENEATH THE STIRRING ICE

I ask Marlowe where the magnum lake trout of Great Slave might be caught. He points to the mouth of the Snowdrift River, which enters the lake just beyond town.

“In the fall, ciscoes move up the river to spawn, and the lakers follow,” says Marlowe. “You want to catch a big trout, you have to first catch a cisco.”

That night, Jennings and I join what seems like the entire village of Lutselk’e after dark, stabbing dip nets into the current to catch the darty little baitfish. The villagers will dry the fish to eat all year. We’re more interested in feeding the ciscoes to lakers. The river is literally flashing with fish, the silver-sided ciscoes slashing upstream. Overhead, the northern lights crackle and swirl and drape the river in an eerie green twilight. Marlowe, who helps us rig the ciscoes in treble-hook harnesses, tells us that the Dene call the lights “stirring ice.” We drift the bait, and in the half-glow of the aurora, we miss one explosive strike after another before finally hooking a couple of 10-pound lakers. It’s well after midnight before we slip into our sleeping bags.

THE DUCKS ARRIVE

On our final day in the Territories, we return to Duhamel Lake, which means “Lake on the Other Side.” Most landmarks here have names taken from the Dene that translate to: “Lake That Freezes First,” “Lake on the Way,” “Big Rock Lake.” Great Slave’s Dene name is translated simply as “Big Lake.”

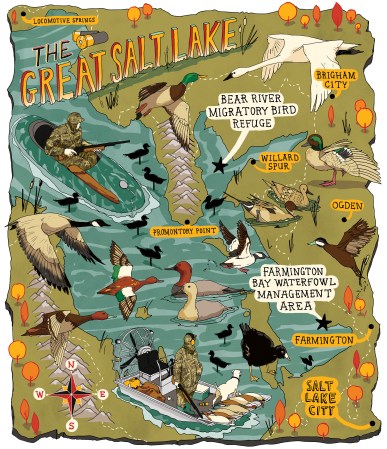

We set our decoys off a different point, and the ducks pour in. The species mix is diverse: mallards, pintails, green-winged teal, buffleheads, both surf and white-winged scoters, long tails. In all, we bag close to 40 birds.

Marlowe comments on our surprisingly good wingshooting. We’re impressed with his choice of spots and anticipation of the ducks’ behavior. This is how a cultural exchange should work, both guests and host learning from each other. The best evidence it’s gone well? Marlowe asks to keep a handful of our “toy-duck” decoys.

We roast a few more ducks for our country-food shore lunch, but even before we’re back in Lutselk’e, word of our hunting success is out. A white van is parked at Marlowe’s house, and as we pull up, a Dene woman rolls down her window. “Got some ducks?” “Of course,” says Marlowe, handing over a clutch of buffleheads. Then he gives her a handful of scoters. “For your granny,” he says. North of 60, when it comes to wild meat, windfalls are for sharing.