We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Whenever I’m with a group of hunters, someone always asks me to name my favorite rifle and caliber. This may sound like an innocent request, but experience has taught me it isn’t. Naming your favorite guns and cartridges is loaded with booby traps. As with talking politics during an election year, naming a favorite gun will lead some people to assume you do not favor (or even oppose) other makes and models, and have no use for other calibers. Invariably, someone will be offended because I haven’t named his personal favorite, and a verbal fistfight will ensue. Also, anyone who is convinced that any rifle or caliber is the absolute best is woefully short on imagination, experience or both.

Having said that, I’ve chosen three rifles from my rack as my favorites, not because I’m convinced they’re the three absolute perfect choices to take all game that walks the earth, but because I’ve hunted with them more than all the other models and calibers put together. Although they are archetypical representatives of the three classes of big-game calibers, I didn’t plan it that way. They were acquired at different times for entirely different reasons. And surprisingly, perhaps, it was the .458 Win. Mag. that came first.

My First “Big Gun”

The story of that much-used .458, which I’ve told before, goes back to my college days, when I fancied myself an up-and-coming stockmaker and Jack-of-all-gunsmithing. Back then I never met a gun that I didn’t think needed one of my stocks, which resulted in the disfigurement of several otherwise fine firearms. In time, however, my stockmaking skills escalated to a level of solid mediocrity, so I decided to build the Big Daddy of all rifles: nothing less than a .458 Magnum, which at some date in the unknown future I would take to Africa to slay elephants and other mighty beasts.

Of course, my buddies made a big joke of such ambitions because they figured my prospects of ever going to Africa were about the same as someone walking on the moon. The rifle was built on a surplus Mauser action I picked up for a few dollars and sent to the Douglas works for the fitting and chambering of one of their barrels. The stock was whittled from a rather plain piece of claro walnut, which was all I could afford at the time. As it turned out, the choice of wood was a good, albeit lucky, one. It has sustained a lot of use and abuse, but it still looks pretty good, as you can see in the recent picture (above).

Back in those days, everything I read about dangerous-game rifles said they should be fitted with express, wide-V, open sights. According to those supposedly first-hand accounts, wherein the storytellers made little effort to restrain their virility, every encounter with a buffalo or elephant was a life-or-death struggle, with blood and testosterone flowing by the buckets. This was why they said that if a scope was to be used on heavy-caliber rifles, it should be set only in detachable mounts, so that it could be quickly removed in tedious situations and the express sights brought into play.

And so I mounted express sights on my .458, the same rear sight, in fact, that Winchester used on its .458 “African” Model 70. But in addition I mounted a 1.5X scope in a quick-detachable system that mounts on the side of the receiver. With the scope removed, the side-mounted base gave a clean, unobstructed view of the open sights, and I figured I was ready for any emergency.

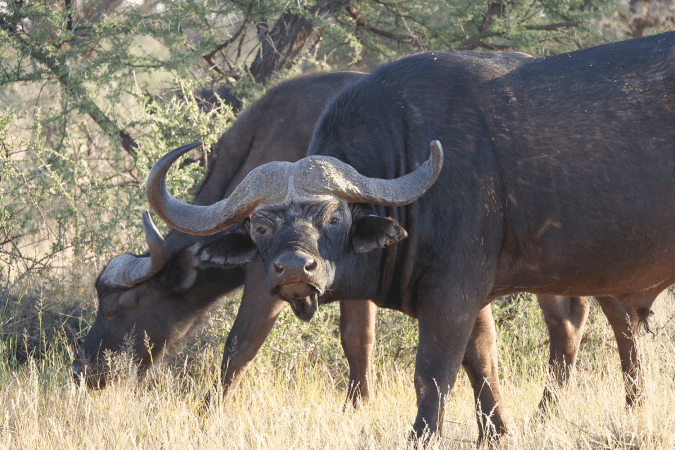

Keeping a promise that I’d made to myself many years before, I brought the homemade .458 with me on my first African safari and used it to take a lion, two Cape buffalo and a couple of elephants.

The following year the .458 and I were back in Africa, where I had the great luck of being invited by the game offices of what was then Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to take part in a Cape-buffalo culling operation. In a single day I got a lifetime of experience killing buffalo and put enough meat on the ground to feed several native villages for weeks.

A few days later I went over to Botswana and took a pair of tuskers with what by then had become my ever-faithful .458, and, for the record, never once did I have cause to take the scope off and resort to the express sights, including a couple of times when I was eyeball to eyeball with elephants in a cranky mood.

More recently, I’ve hunted Africa’s dangerous game with other rifles in many other calibers, but if I had to hunt the big stuff with only one rifle, it would be my old homemade .458, loaded with handloaded 500-grain Hornady solids. It’s the stuff dreams are made of.

A Deer Rifle to Die For

It’s been said that I’ve championed the .280 Remington cartridge much as Jack O’Connor did the .270 Winchester on these pages before me. If it appears that way, it’s more by accident than intent. The simple truth of my assumed love affair with the .280 Remington dates back over a quarter century, when I met ace stockmaker Clayton Nelson at a swanky hunting conference in San Antonio. Jack O’Connor was also there, and it wasn’t long before the three of us found the bar and fell into a thunderous discussion about hunting rifles.

Nelson was the stockmaking guru who designed and made the beautiful stocks on the elegant Champlin rifles, and he had just opened his own shop. I happened to be in the market for a new hunting rifle about then, so after a second round of drinks—and considerable encouragement from O’Connor—I arrived at the conclusion that a rifle by Nelson would be about perfect for several sheep hunts I had planned and the African game I would be hunting about three months hence.

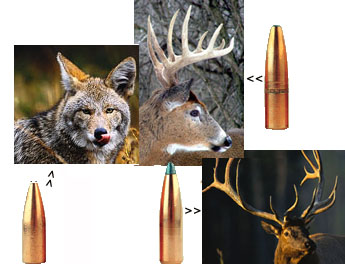

The rifle we agreed on was to be stocked in Nelson’s classic style and built around a pre-1964 M-70 Winchester action. The logical caliber choices for such a rifle were any of the “three sisters”: the .270 Win, .30/06 or .280 Rem. Since I already owned and had hunted with the first two, the .280 was an easy choice. Besides, despite the .280’s rather paltry factory ballistics, it was a handloader’s dream because of the wide assortment of excellent bullets available. With Nelson and O’Connor concurring, the caliber was decided, with a proviso that the rifle had to be delivered in time for my rapidly approaching first safari.

The rifle arrived with a couple of days to spare, and I’d never laid eyes on anything prettier. The stock was a gorgeous piece of real French walnut Nelson had been saving for a special project and was checkered with his distinctive fleur-de-lis and point pattern. It’s the kind of rifle some people look at and say, “That gun is too beautiful to take hunting.” But I did—many, many times over the years to come.

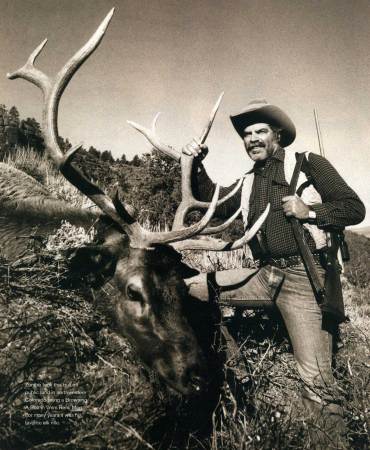

On that first safari, along with my homemade .458 Mag. I took a rifle in 7mm Rem. Mag., which I intended to use for the bigger plains game such as kudu, sable and gemsbuck. But as it turned out, I shot only two species with the 7mm Mag., a zebra and a roan antelope. It seemed that every time I had a shot at a good trophy the Nelson .280 happened to be in my hands, and with every shot I became more impressed with how the .280 and the 140-grain Nosler Partition handloads performed.

During the years I lived in northern Arizona and was feeding a growing family on whatever game the hunting seasons offered, the .280 Nelson rifle became a staple tool for everything from pronghorn to elk. Only once did I vary from my handloaded 140-grain Noslers. That was for a safari into the snake-infested jungles of the southern Sudan in search of the reclusive bongo.

A bongo bull is a thick-bodied antelope weighing about 500 pounds. It is so tough to hunt in its element that the hunter-success ratio is only about 30 percent, even among experienced hunters mad enough to hunt them. Given the rarity of spotting one, most hunters opt for a heavy-caliber rifle, usually in the .375 H&H class, to make sure the animal stays down if they’re lucky enough to get a shot. My approach to the caliber-vs.-bongo question was simply to load some .280 Remington ammo with the then-new 160-grain Speer Grand Slam bullets. Perhaps I was luckier than I deserved to be, because the full-body-mounted bongo that now stands in my trophy room never took a step after one shot from the .280.

My worst day with the Nelson .280 was on an elk hunt in Idaho’s Selway wilderness. My hunting pal and I tied our horses to a tree while we glassed some open meadows. While we were gone, my pal’s horse decided to scratch his chin on the unprotected butt of the rifle in my scabbard. There was a steel bridle bit in the nag’s mouth, and as he scratched it dug deep slashes into the beautiful French walnut. Never again have I left a rifle in a scabbard when I’ve gone for a stroll.

My Nelson .280 rifle made more trips to Africa and was slung over my shoulder on many climbs up the sheep mountains of Alaska, British Columbia and the Yukon.

Nowadays when I read about the turmoil in the Middle East I think of a time when Fred Huntington and I set out on a New Year’s day to hunt our way around the world. Our main goal was to take what has become known as the Iranian “Grand Slam” of ibex plus the Armenian, red and Ural varieties of wild sheep.

About midway through the hunt a blizzard hit and we were stranded in a sheepherder’s hut with nothing much to do except look at each other and nothing to eat but greasy mutton boiled over a sheep-dung fire. On the third day of this idyllic isolation, the weather began to clear a bit and I noticed a flock of crows squawking in a snaggy tree about 200 yards distant. So why not ease the boredom a little by taking a shot at them with my .280?

Our Iranian guides and the interpreter thought it was ridiculous that I would shoot so far at such a tiny target and made it quite clear, with much laughter, that I could only make a fool of myself by trying. But I took a solid rest, and when the crow on the uppermost branch disappeared in a puff of black feathers the Iranians’ jeers were replaced by dark scowls. They remained sullen and moody for days after because it was I, not they, who had the last laugh.

Perfection for Elk and Bears

Rifles made by the David Miller Company of Tucson, Ariz., are widely considered the finest hunting rifles ever created. Note the emphasis on hunting, because many of today’s custom gunmakers have strayed from the basic concept of making rifles to be actually used, and instead fashion lavish showpieces quite unsuited to the rugged realities of plains, mountains and saddle scabbards. In contrast, beautiful as a Miller rifle might be, the company’s underlying philosophy is to eliminate, to whatever extent possible, mechanical failures in the field. Of course, hunters who want only the best pay dearly for this assurance.

I first learned of David Miller back in the late ’70s when he called and said he was building a scope-mounting system I should try. Somehow I misunderstood and thought the Miller system was an improvement over the quick-detachable mounts that were all the rage back then. So rather than have his mount attached to one of my rifles, we made a deal for him to build a complete rifle with express-type sights that I mistakenly thought would complement his detachable scope mounts.

We finally settled on the rifle being a .338 Winchester Magnum because I’d been having great success with that caliber on elk and Alaskan bears. But the .338 Mag. that I’d been hunting with was one of my all-time ugliest, do-it-yourself stocking jobs, and even without seeing a Miller rifle I figured it had to be better than what I had. This pretty well explains why I was so utterly dumbfounded when I opened the case from Miller and beheld the most magnificent hunting tool I’d ever laid eyes on.

To be sure, the express sights were there just as I’d specified, with a quarter rib machined one-piece from the barrel blank. But they were, and are, essentially useless, because the Miller scope mount, far from being detachable, unites the scope with the receiver in a continuous, interlocking cradle of steel (see photograph below). I sighted-in the rifle over two decades ago, and despite the rigors of freezing mountains, scorching deserts and thousands of miles on airlines, bush planes, safari trucks and horseback (not to mention tumbling down mountainsides), the point of impact is still exactly where it’s always been.

For big bears like the Kodiak brown that I took several years back, the .338 Winchester Magnum loaded with 250-grain bullets is about as good as it gets. The same goes for hunting moose. And nothing makes an elk guide happier than seeing his hunter show up in camp with a .338 Magnum.

I once hit an oncoming lion on the point of the shoulder, and the 250-grain Partition slug exited at his hip after transiting his body diagonally. Game over.

A couple of other times in Africa I’ve had only the Miller .338 in hand when I came across Cape buffalo that were too good to pass up. There’s nothing much exciting to tell about either of these two events—just two shots and two very dead buffalo. This is why there have been a couple of times I’ve taken no other rifle to Africa save the Miller rifle. It has the range and accuracy for smaller plains game, is a perfect match for bigger game such as eland and has the authority, when needed, for lion and even buffalo. Two leopards I’ve killed with the Miller .338 were dead before they hit the ground.

But before we get bogged down on the merits of the .338 versus other calibers, let’s ask whether my rifle has been so successful on so many hunts because it’s a .338 Mag. or because it’s a good rifle that I can shoot well. I think my old guide and hunting pal, George Hoffman, explained it best in his book, A Country Boy in Africa: “He [Carmichel] hunted with me in Botswana some years ago” he wrote, “and uses the .338 to its fullest.”

These three rifles stand together in my gun rack, like three old men telling hunting tales and sharing memories of days past, of shots well done and misses too, shots close and far, some quick and deadly and others just lucky. And when I trace my fingers along their scarred stocks and feel the cool steel of the barrels through which so many bullets have passed, I can hear the whisper of the sheep mountain and listen to the songs of places far away. And I dream of hunts to come.

1) .458 WIN. MAG.

The homemade .458 that Carmichel built back in his college days still looks pretty good, considering the many years of safaris it’s been on. Carmichel built the rifle on a surplus Mauser action he paid a few dollars for. He had Douglas fit and chamber one of its premium barrels for the action but did all the stock work himself. A detachable scope mount allows quick access to the express sights, which are the same ones Winchester used on its .458 “African” Model 70.

2) .280 REM.

Strong urgings from Jack O’Connor and stockmaker Clayton Nelson led Carmichel to build this magnificent pre-1964 Model 70 in .280 Rem. Nelson used a choice piece of French walnut, then checkered it in his distinctive fleur-de-lis and point pattern. Carmichel chose the .280 because of the wide assortment of bullets available in 7mm for handloading. He’s taken everything from deer to Iranian ibex with it.

3) .338 WIN. MAG.

Beautiful as David Miller’s rifles are, the Tucson gunmaker’s philosophy is to build firearms that eliminate mechanical failures in the field. Below, Carmichel’s .338 features Miller’s signature scope-mounting system, which unites the scope with the receiver in an interlocking cradle of steel. Carmichel once hit an oncoming lion on the point of the shoulder with this rifle. The 250-grain Nosler Partition exited the hip after ranging through the cat’s entire body diagonally. Now that’s performance!