Last November 20, the Canadas came in continuous cycles, in waves of 25 and 30, but they refused to commit. It was cloudy and gloomy, and the geese were flanking to the far left or right of Mike Cunningham’s blind near Dwight, Nebraska. Cunningham, a waterfowl outfitter, couldn’t call the shot. Every time he stood to change the decoys, another batch of birds arrived and he gave them another chance, only to see them flare again.

Exasperated, at 9:10 a.m., he took out his cell phone. The one person who could fix this problem was sitting at a kitchen table 1,500 miles away. Despite the two-hour time difference, Ralph Kohler had been awake as long as Cunningham.

“I’m getting beat up out here,” Cunningham, 53, told Kohler, whom he first met and hunted with in 1976. Kohler asked a few questions about the conditions and the setup and knew immediately that Cunningham’s decoys were too far out in the lake. He advised moving a dozen decoys in to 35 yards in front of the middle blind. “Do that and they’ll skirt right in front of you,” Kohler said.

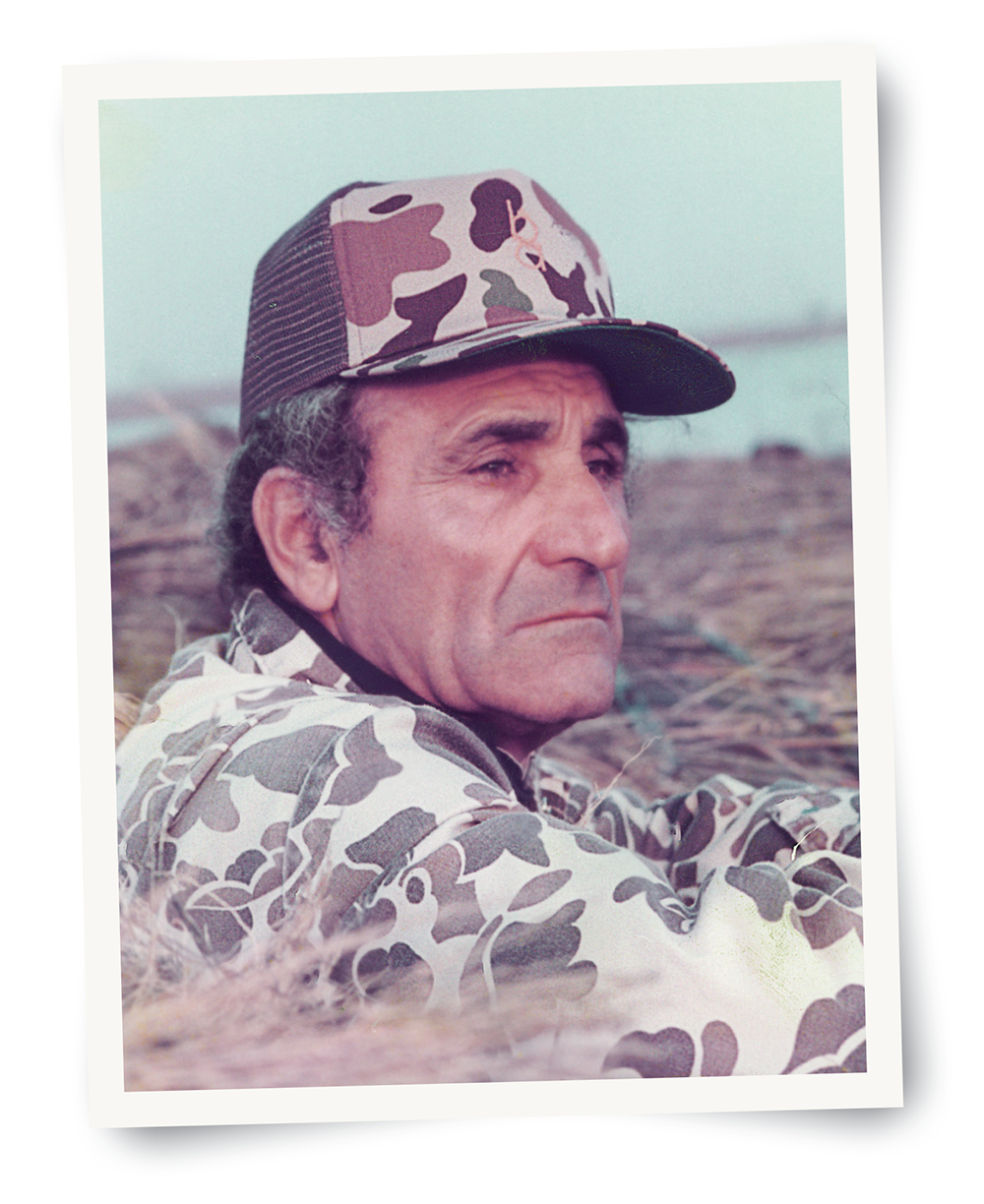

Thirty minutes later, Cunningham called Kohler back. “You’re a genius,” the outfitter gushed, and then he reported that, after the alteration, his clients bagged 29 honkers in short order. Cunningham calls the 98-year-old Kohler every single day during the waterfowl season, usually by 7:30 a.m. Pacific Time, to describe the birds’ behavior, along with the wind, the sky, the clients. It’s not out of debt for the four decades spent sitting next to his mentor, but more out of their mutual respect for wildfowl and a desire to retain the connection forged over 40 years.

When this year’s Central Flyway waterfowl season begins on October 1, it will be just the fourth opening day Kohler has missed since the late 1920s. The first was because of a ballroom dancing tournament in the 1980s. The other three have come recently and successively since 2014, when, at age 96, Kohler retired as a commercial waterfowl guide and moved from Tekamah, Nebraska—where he’d spent nearly his entire life—to Palm Desert, California, to be closer to his children and grandchildren.

He left behind a legacy: a registered business more than 75 years old, thousands of clients, and the lessons gained over the course of 65,000 hours spent hunting and studying waterfowl.

He also influenced several generations of Nebraskans who sponged any bit of knowledge they could get from the man who documented every detail of his career in hundreds of hand-scrawled notebooks. Kohler’s experience and meticulous record keeping helped him produce big days for his clients. So detailed are his notebooks that he knew the exact time—to the minute—hunters could poke their heads out to see birds: 12:08 p.m. was the best time, but 9:23 a.m., 10:17 a.m., 3:10 p.m., and 4:25 p.m. were pretty good, too. And he didn’t call everything in the air, even if it was in range. He called shots only when birds had cupped their wings toward waiting hunters. “If they’re not coming, leave them alone,” he says. “Timing is everything.”

Even today, from an air-conditioned kitchen in the middle of the Sonoran Desert, Kohler is still fooling geese with his refined sense of timing and his knowledge of where and how to set decoys on any given day.

A LINK TO PIONEERS

Ralph M. Kohler is one of the last living connections to a period of hunting that outdoorsmen today can only read about: live decoys, unplugged shotguns, mouth calling, and lead shotshells that cost 65 cents a box. Kohler started hunting in the 1920s, before Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic (1927), before the stock market crash of 1929, and 10 years before Ducks Unlimited was founded (1937). Married in 1935, Kohler will celebrate his 81st wedding anniversary to the former Dorothy Reddig on September 16.

Kohler was born in Chicago on January 6, 1918, the same year the Migratory Bird Treaty Act brought an end to market hunting and established bag limits, season dates, and regulations tailored to specific migratory flyways. When Kohler was 18 months old, his father died and he and his mother moved to Tekamah, where her relatives had made their living as market hunters. In Tekamah, Kohler’s uncles Manie, Max, and Skip allowed the young boy to tag along on Missouri River waterfowl hunts.

“My uncles always told me to watch the birds. The birds would tell me all I need to know,” Kohler says, staring at the ceiling in his dining area. “I could see that was to be my way of life, I just loved it so much. The most beautiful sight in the world is to have a clear blue sky, a cold day, that north wind, and have a bunch of ducks and geese go out, turn, and come back against the wind, all them wings cupped.”

Like a kid who lies awake at night rolling an imaginary basketball off the tips of his fingers to perfect his jump shot, Kohler spent hours in the wet fields of his family’s farm looking up to the sky during the spring migration. He studied the birds and their patterns and sounds so well that he could identify species in the dark.

In 1931, back when plugged shotguns were not required for waterfowl hunting, his Uncle Skip bought a Remington five-shot automatic with a four-round magazine extension. On his first outing with the gun, the 13-year-old Kohler read the signals a group of honkers were sending each other, accounted for a 20 mph wind, and waited for the flock to get within 35 yards. He downed nine geese in nine shots, and his uncles told the story for years. Kohler quit school in the seventh grade but applied his love for mathematics as he worked in a local machine shop. A couple of years later, he married Dorothy. In 1938, he founded his own business, Kohler Welding and Machine Shop, which he operated for 41 years.

As a 13-year-old, Kohler downed nine geese in nine shots. And his uncles told the story for years.

With his business taking much of his time and his love for hunting only growing, along with his family—a son first, followed by two daughters—Dorothy gave him an ultimatum: If you’re going to continue to hunt, you must get paid for it. At the end of the 1938 season, Harold Vatruba from Des Moines, Iowa, called. Referred to Kohler by the Chamber of Commerce, Mr. Vatruba was looking for a guide on the Missouri River. Kohler’s relationship with Vatruba and his friends laid the foundation for a waterfowl guiding business that operated until 2014. Kohler’s price in 1938 was $10 a person. It rose to $50 by 2013. During his very last season—spring 2014—the price was $100, well below the $300- to $400-per-day average for the area. Friends and family urged him to charge more.

“I always had the feeling that people who loved to hunt couldn’t pay more than $100,” Kohler says. “It didn’t make that much difference to me.”

CHANGING WITH THE TIMES

When the Army Corps of Engineers channelized the Missouri River in the mid-1950s, the sandbars and side channels that Kohler had grown up on disappeared. Kohler knew the end of hunting on the Missouri was coming, so he bought the farmland where he had watched geese as a child. Remembering boggy areas on the property, Kohler reckoned that with a little work, he could create his own waterfowl habitat. In the summer of 1956, he built the first of four lakes on the farm. The ducks began enjoying the water as soon as it was pumped in, but Kohler worried the geese might not use the engineered habitat.

On Friday, October 5, 1956, the day prior to the season opener, Kohler sat in a field of unpicked corn, ate his lunch, and tuned his radio to Game Two of the World Series. As the Brooklyn Dodgers were beating up on the New York Yankees, Kohler heard a honk, then another, then saw a couple hundred geese, wings cupped, drop into his lake. Kohler believes his man-made lake was the first of its kind in Nebraska, and it made his reputation as a guide. He brushed in eight blinds, capable of handling 48 hunters at once, a capacity that was filled every year when the Jiffy Lube Company bought out all of his spots for corporate retreats. Kohler’s average daily client count was 20 to 30 hunters.

Commercial waterfowl decoys in the late ’50s were crude, flimsy affairs, and Kohler couldn’t find dekes that would last more than a single season. So he and his friend Monte West decided to make their own in the machine shop. Using ¹⁄₈-inch forming board and 40 percent resin, K&W decoys were hand-laid, cost $64 to $78 a dozen, and were made to last a lifetime. In 1962, after four years, they shut down the business and sold the equipment; it was too much to handle with his other interests. Kohler hunted over his own decoys until the late 1980s, when collectors bought them from him.

Another product that emerged from the machine shop was the Kohler Blind, which was 12 feet long and fabricated from steel. Kohler made 419 of them from 1956 to 2005, one by one, and only when someone placed an order. The price: $875. Cunningham has taken over the blind business, kept the Kohler name, and still runs design changes by his mentor before implementing them. The price today: $6,495.

Kohler didn’t collect guns or hoard memorabilia. Everything he owned he used in the field. When he moved to California, he sold everything—even small mementos like a Zippo lighter he got in 1957 for being a judge in a duck-calling contest. It’s common for waterfowl guides to have a variety of goose and duck calls on their lanyards, but Kohler didn’t own a call of his own until he was 55 years old. He mouth-called until October 19, 1973, when his voice went hoarse on a day his crew bagged 87 snow geese. His ability to hit the high notes never came back, and after that day, he used the only call on his lanyard, designed and made by his friend Monte West.

Kohler’s shotgun lineup included a Winchester Model 21 he used in the 1940s and ’50s and a Browning A5. The last gun Kohler carried to his blind was a Beretta A303, but he used it mainly to dispatch crippled birds. At the age of 86, he left his gun at home. After nearly eight decades of shooting in the blind and on the trap field (both he and Dorothy were inducted into the Nebraska Trapshooting Association’s Hall of Fame), Kohler no longer had the desire to shoot.

Kohler’s reticence was caused partially by clients who were too casual with waterfowl limits, and he didn’t want to be blamed for any violations. One day, Kohler and one of his guides were left with 23 ducks after their clients took the birds they wanted. The limit was five apiece, and Kohler immediately notified his local game warden of the over-limit. From then on, he asked his clients how many birds they were willing to take before the day started.

“If the out-of-doors was full of Ralph Kohlers, we wouldn’t need game wardens,” said Dick Turpin, the former head of the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, in a January 2000 article from the Omaha World-Herald.

About 50 years ago, Kohler stopped shooting ducks altogether. Cunningham remembers one specific day—117 mallards and 34 geese in the bag—when Kohler’s group gathered in front of a shed for a group photo. As the hunters marveled over the bounty, Kohler disappeared into the crowd, trying to slink away from the camera’s lens. He didn’t want to be part of what he considered inappropriate celebration of the body count. “For Ralph, it was never about the shooting,” Cunningham says. “It was about the shot. He used to say, ‘It would be a better day if these birds could jump up off this pile and fly away so we could do it again tomorrow.’”

CHANGING MIGRATIONS

Kohler kept note of migration patterns in the Central Flyway, documenting a westward shift in the fall flights of the snows and blues in the 1980s. He attributed the change to the waterfowl refuges constructed in his area. While he used to see a couple hundred geese in a flock, the refuges worked so well in producing and holding birds that flock sizes ballooned to several thousand, and geese overflew his area to feed and roost around the refuges to the west.

When Kohler started guiding, snow and blue geese were done migrating by October 10. By the end of the ’80s, the migration peaked on November 8. It now happens well into December.

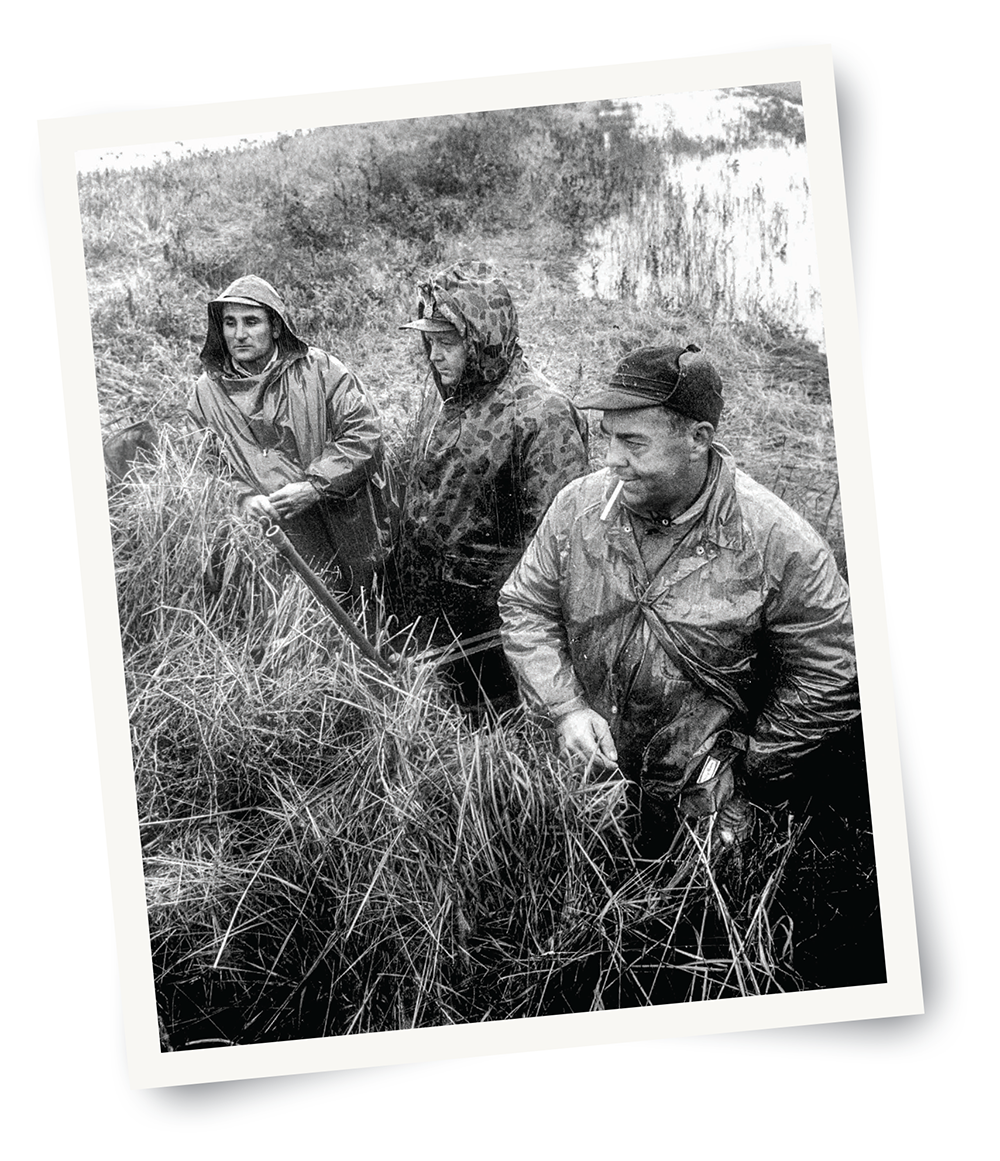

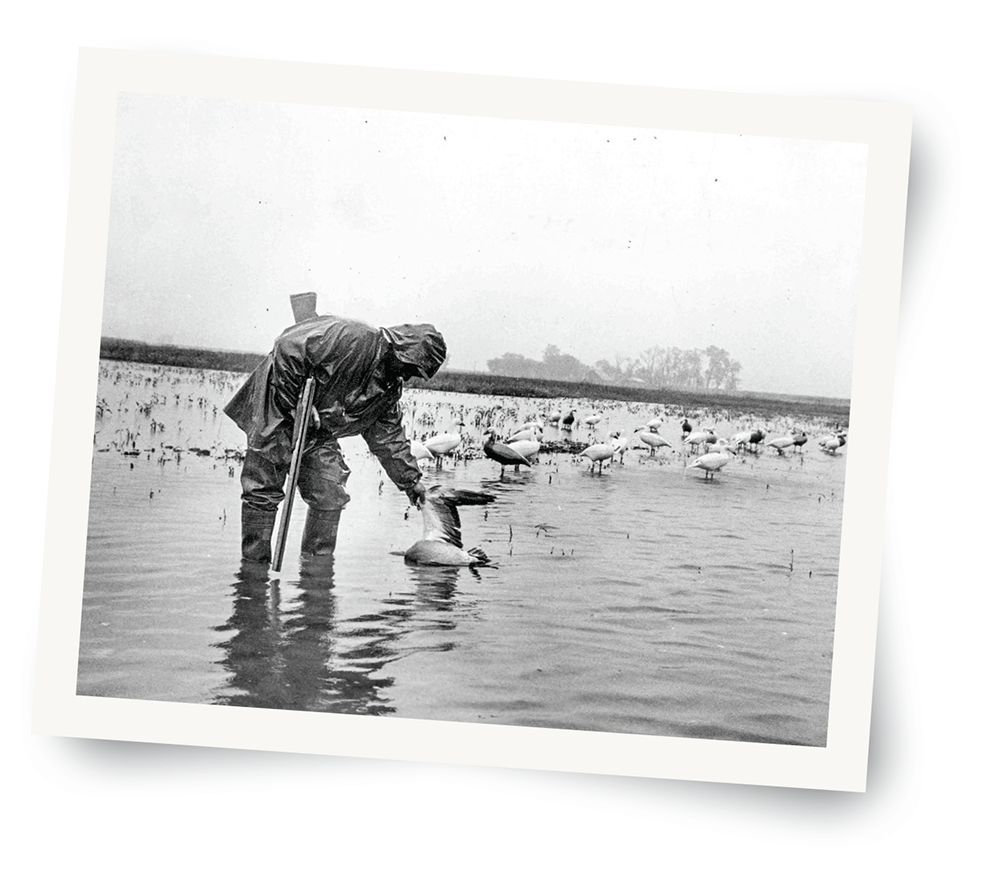

While the migrations might have changed, the birds didn’t, and fooling a smart adversary is what motivated Kohler to get up every morning at 3 a.m., drive out to his lakes, and wade around in the muddy dark setting out decoys.

“I look at him like a guy that dropped in from another planet, like he’s superman,” said Mark Davis, a former outdoor writer for the Omaha World-Herald, who had the good fortune of joining Kohler on his last hunt, on March 27, 2014, a cold, rainy day that resulted in the harvest of a single snow goose. “I expected it to be a last-rites hunt, but I didn’t expect what I found. He was more than capable of doing anything.”

Kohler was frustrated with the lack of action on this day, and he made several trips into the water to rearrange the decoys. “I don’t remember him ever looking tired,” Davis said. “But he would stop talking, even in the middle of a sentence, to watch the geese go overhead.”

Davis said the lesson he left with was that an animal didn’t have to be killed for a hunt to be considered successful. “That was one of the best hunts I ever had, and I didn’t fire a shot.”

That’s the way Kohler would want it, a remembrance of the experience of the hunt, and an appreciation of the birds, and of fooling them. After all, it wasn’t a gun, a call, a dog, or a decoy that made Kohler a great hunter. Rather, it was his ability to understand the birds. For nearly 80 years, he made it his business to fool them.

He still does, even if it’s over a telephone, hundreds of miles from his beloved Nebraska.