W e had run across a great deal of buffalo sign and had encountered one herd of very smart and cautious buffalo. We glimpsed the last of the herd of 30 or 40 of the big, black cattle as they disappeared into a very dense thicket about a quarter of a mile in diameter. They had fed and watered, and they were planning to lie up for the day in the cool seclusion of the brush.

“I don’t think it will be hard to get them out of there,” said John Kingsley-Heath, our outfitter and white hunter. “We’ll get out and wait here. Then I’ll have Musioka [BRACKET “the gunbearer”] drive around on the far side of the thicket, blow the horn and make a noise. When the buffalo come out, you and Eleanor can knock off a couple if they are worth shooting!”

This sounded very simple. We got out of John’s hunting car, and Eleanor and John took a stand behind one tall anthill and I behind another. Eleanor had the Winchester Model 70 .30-06 she had used on tigers in India the year before and I a restocked Winchester .375 I had carried on many hunts in far countries. She was loaded up with 220-grain solid bullets and I with 300-grain solids. John had his life insurance-an old Westley-Richards .470 double-ejector rifle.

In a few minutes we heard Musioka blowing the horn on the hunting car. Then we heard him pound the side of the car with the flat of his hand. The brush cracked and we saw the vague shapes of buffalo moving around just inside the thicket. But they wouldn’t come out. Apparently they knew that if they came out in the open they stood the chance of getting bushwhacked.

An enormous, dry and thinly populated plateau the size of Texas, Bechuanaland Protectorate, which has recently become the independent republic of Botswana, is about as flat a country as can be found on this earth. Except for half a dozen or so low hills a few hundred feet high, no part of the country is more than 50 feet lower or higher than any other part. Located in the north are the famous Okavango Swamps-thousands of square miles of shallow water, low sandy islands, bushes, palm trees and tsetse flies.

There are lions in the Okavango-they’re about the biggest and meanest in Africa. There are also elephants, giraffes, hippos, thousands of buffalo and strange swamp-dwelling antelope called red lechwe and situtunga, kudu, sable, impala, crocodiles, leopards and warthogs by the tens of thousands.

Along about 2 o’clock that same day we put lunch things away in the chop box, got into the hunting car again and took off. Musioka the gunbearer stood behind with his head out the lookout hole in the top of the car. We saw hundreds of warthogs, and also hundreds of red lechwe grazing in the grassy meadows close to water.

We were at least 30 miles from camp, and for 20 miles we had broken trail through the brush. Now we started to follow our tracks back toward what passed for a road-simply a track made by hunting cars and trucks.

Suddenly Musioka tapped sharply on the top of the car and said “M’Bogo!” That is Swahili for buffalo.

John stopped the car and a moment later said, “There they are, moving in the brush to the right, a whole herd of them. They’re coming this way!”

We were on the edge of a little embuga, or open grassy space in the brush. It was about 50 yards wide and something over 100 yards long, but all around it the brush was pretty thick. Slowly the buffalo started to cross the embuga-cows, calves, bulls. The wind was blowing gently from them to us. We could smell their cowlike odor.

Presently as the rear section of the herd passed, John whispered sharply: “There’s a good bull, Jack-that one on the right. I think you ought to take him!” There were two bulls together, one noticeably larger than the other.

The buffalo walked quietly along broadside about 100 yards away. I held the intersection of the crosswires ithe Weaver K3 scope right on his shoulder blade about one third of the way down from the hump, in line with the place where his left foreleg joined the body. I hesitated for a second, and then the darned bull started to turn, and I knew that if I was going to shoot this particular bull I had better shoot then. I squeezed the trigger. The buffalo stumbled, almost went down and then started off again, but with the plunging gallop of an animal with a broken shoulder. I quickly worked the bolt and sent a 300-grain solid bullet raking through the buffalo’s ribs from the rear. Then the buffalo and his companion, the smaller bull, were in the brush.

“Well,” John sighed, “a wounded buffalo! The way he was hit I doubt if he’s gone far. Let’s follow him up!” He turned around and extended his hand to Musioka, who handed him his old Westley-Richards .470 double rifle. I filled the magazine of my .375 and put another cartridge in the chamber.

We took up the track. Musioka, who was unarmed, did the tracking. John and I pussyfooted along, watching. We had not gone 100 yards from where we had seen the buffalo last when Musioka extended the flat of his hand toward John and me as a signal for us to stop. He pointed into the brush.

The patch into which the tracks led was very thick, but by getting down on our knees we could see the front feet of a standing bull and a formless black mass that was the wounded bull lying down. They were not over 30 feet away.

John put his lips to my ear. “Better not shoot again until you know which way he’s facing,” he whispered. “He’s down and sick but very much alive!”

What moved them I cannot say.

Musioka thought he had figured out which end of the buffalo was which and was trying to tell John. Maybe the buffalo heard him. Perhaps he heard us breathing. Maybe the slight breeze had shifted a bit. Anyway, the wounded bull suddenly floundered to his feet and both buffalo thundered away through the brush. John raced after them. I hadn’t traveled more than 50 yards when ahead of me in the thick brush I heard John’s .470 bellow twice.

“Well,” I thought, “John has shot the wounded buffalo!” I turned around to see Musioka behind me. “Kufa-finished,” he said in Swahili.

Just as he said that, I heard the thump of hoofs and crashing of brush to my right. To my astonishment I could see the plunging shadowy form of the bull with the broken shoulder. I threw up the .375 and gave him a high lung shot through the brush. He disappeared. In a moment Musioka and I found John standing beside a dying buffalo. “Hell, John,” I said, “that’s not the wounded one. He just passed me at 40 yards or so, and I took a poke at him.”

“I know it,” he said, “I should have had a good shot at the wounded fellow, but this bloke here came for me when I was about to shoot his pal. I had to let him have it. Look, he’s beginning to stir. Let him have another. I’m not too well fixed on cartridges.”

I gave the second buffalo a finisher, and we went off after the bull with the broken shoulder. He was very sick and had not gone over 50 yards from the place where I had put that last bullet in him. He was lying down again in brush watching his back track.

We tried to work around to get another angle, but the buffalo detected us. I heard him flounder to his feet, but I could not see him. John could. He put in two shots from his double. We heard brush crash for a second or two. Then all was quiet once more.

We were not far from the car, so the three of us went over to see how Eleanor was getting on. We found her perched on the top, her .30-06 in her hand. She had a 220-grain solid in the chamber and her right thumb was on the safety. Her face wore the look of one who is resolved to die bravely. “He went over there and stopped!” she said, pointing to a thick patch of brush about 60 yards away.

I stood by the car and watched John sneak up beside Musioka. Then I saw him kneel down and aim. A moment later I heard the .470 roar and saw it rise in recoil. Then he shot again. Once more I heard the wounded bull go crashing through the brush. Then quiet. He had either fallen or stopped.

We drove around and came to the spot where we’d heard the bull give his last bellow. I saw him lying inert in a little opening ahead. “There he is!” I said. “Dead as a mackerel.” An instant later that damned bull was on his feet and charging, bouncing along on his one good front leg, blood streaming out of his nose. The car was still moving when I jumped out. The scope was full of buffalo head when the .375 went off.

Jumping from the moving car had me off balance. One foot went into a warthog hole and I started to fall the instant after I had shot. As I was falling I could see the buffalo falling, too, and at the same instant I heard a shot.

I looked up as I scrambled to my feet and cranked another cartridge into the chamber of the .375. Musioka had his head and shoulders out of the manhole in the roof of the hunting car and in his hand was John’s .470 double.

Eleanor and John piled out of the car. John examined the dead bull.

“Not bad shooting under the circumstances,” he said. “He’s hit twice in the brain and once in the boss of the horn. You know, Musioka has never shot the .470 before. In fact he’s never shot anything but a .22. But jolly good! The bugger is dead. For an instant I thought he was going to knock the car about a bit!”

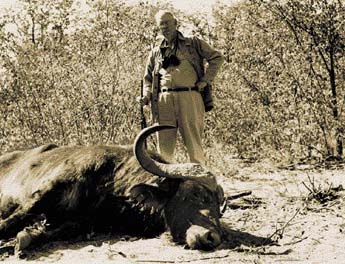

By this time it was getting gloomy there in the brush but we took a few pictures, counted the bullet holes on one side, turned him over and counted the holes on the other. Excluding the final three head shots, this indestructible buffalo had seven shots in his body. Every one of those shots went through either the shoulder or the lungs.

“I don’t get it,” I said as we looked the bull over. “This thing should have been dead at least a half-hour ago. It strikes me that the only sure way to kill a buffalo is to shoot him a dozen times with a 20 mm and take out his guts and bury them, then cut off his head, tie stones to it and sink it in a lake.”

“Wouldn’t do any good!” John said. “All these swamps are shallow. Water isn’t deep enough!”out 60 yards away.

I stood by the car and watched John sneak up beside Musioka. Then I saw him kneel down and aim. A moment later I heard the .470 roar and saw it rise in recoil. Then he shot again. Once more I heard the wounded bull go crashing through the brush. Then quiet. He had either fallen or stopped.

We drove around and came to the spot where we’d heard the bull give his last bellow. I saw him lying inert in a little opening ahead. “There he is!” I said. “Dead as a mackerel.” An instant later that damned bull was on his feet and charging, bouncing along on his one good front leg, blood streaming out of his nose. The car was still moving when I jumped out. The scope was full of buffalo head when the .375 went off.

Jumping from the moving car had me off balance. One foot went into a warthog hole and I started to fall the instant after I had shot. As I was falling I could see the buffalo falling, too, and at the same instant I heard a shot.

I looked up as I scrambled to my feet and cranked another cartridge into the chamber of the .375. Musioka had his head and shoulders out of the manhole in the roof of the hunting car and in his hand was John’s .470 double.

Eleanor and John piled out of the car. John examined the dead bull.

“Not bad shooting under the circumstances,” he said. “He’s hit twice in the brain and once in the boss of the horn. You know, Musioka has never shot the .470 before. In fact he’s never shot anything but a .22. But jolly good! The bugger is dead. For an instant I thought he was going to knock the car about a bit!”

By this time it was getting gloomy there in the brush but we took a few pictures, counted the bullet holes on one side, turned him over and counted the holes on the other. Excluding the final three head shots, this indestructible buffalo had seven shots in his body. Every one of those shots went through either the shoulder or the lungs.

“I don’t get it,” I said as we looked the bull over. “This thing should have been dead at least a half-hour ago. It strikes me that the only sure way to kill a buffalo is to shoot him a dozen times with a 20 mm and take out his guts and bury them, then cut off his head, tie stones to it and sink it in a lake.”

“Wouldn’t do any good!” John said. “All these swamps are shallow. Water isn’t deep enough!”