We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

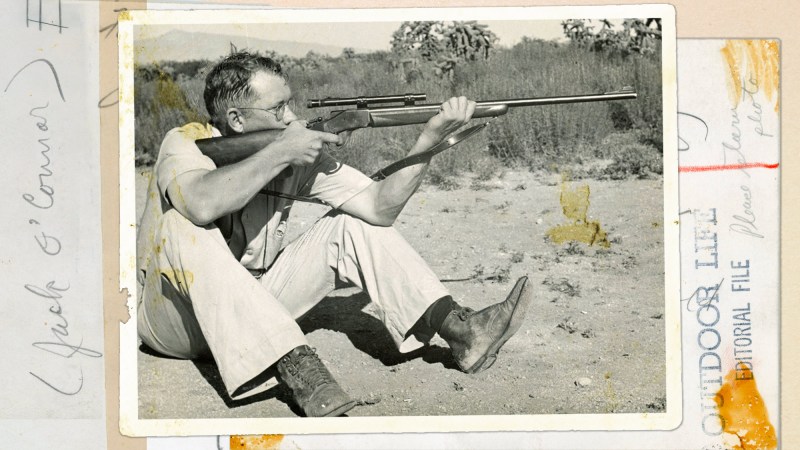

January 22, 2002, marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Jack O’Connor, this country’s foremost gun and hunting writer. O’Connor, who died in 1978 just two days short of his 76th birthday, was born in Nogales, Ariz., where he grew up in what he fondly described as “the last frontier.” Square-jawed and steely-eyed, Jack O’Connor was a prime example of that bedrock stock that won the West.

O’Connor was the product of a hard land and a difficult childhood. His parents drifted apart and then divorced when he was quite young. Fortunately for O’Connor, his maternal grandfather, James Woolf, was a key formative influence during O’Connor’s boyhood and saw to it that the youngster had ample exposure to the outdoors.

“Bird hunting was grandfather’s dish,” O’Connor would reminisce in one of his literary works. Woolf, who hunted birds with a vintage Purdey, endowed his youthful protégée with a sense of style and an appreciation for fine guns that would be reflected in O’Connor’s writings.

From O’Connor’s mother, who was a teacher, came a recognition of the importance of education. Following a short stint in the Army, O’Connor pursued undergraduate studies at Arizona State Teachers College and the University of Arizona. A few years later, after earning a master’s degree in English from the University of Missouri, O’Connor married Eleanor Bradford Barry. Theirs would be a marriage marked by mutual devotion, countless wonderful days spent afield together and the rearing of four children.

After he married, O’Connor taught college (first in Texas and then in Arizona) while moonlighting as a reporter for local newspapers and the Associated Press. O’Connor developed the discipline and sound work ethic that would be among the hallmarks of his career during his early adulthood and the Great Depression. He wrote two novels in the early 1930s, but as his family grew, O’Connor turned to magazine writing for additional income. Since he had always been an avid hunter, the major outdoor publications were logical outlets.

O’Connor found his métier in writing on guns and hunting. In the first chapter of one of his books, The Hunting Rifle, he would provide an introspective view of the keys to his success. “No man’s opinion is any better than his background, his experience and his general common sense,” he commented. O’Connor then hastened to add that he disliked words such as “authority” and “expert” when they were “applied to those who write about guns, shooting and hunting. I am not a ballistician or a gunsmith. I write about rifles as a user and lover of rifles who tries his damnedest to be honest.”

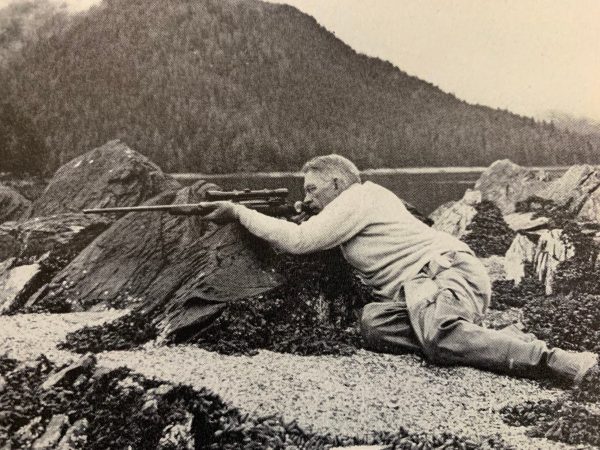

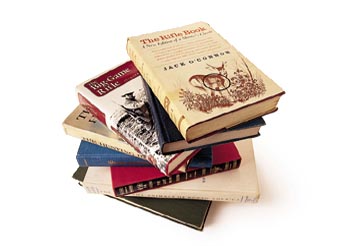

His love of guns and their uses in sport, along with a real feel for words and a transparent honesty, helped make O’Connor a great writer. He poured emotion into his columns, feature articles and books. Most of these were written over the course of more than three decades, beginning in 1939 when he became associated with outdoor life. As the magazine’s Shooting Editor he was insightful, opinionated and extremely influential. Almost single-handedly he popularized the flat-shooting, smaller centerfire calibers (most notably his beloved .270).

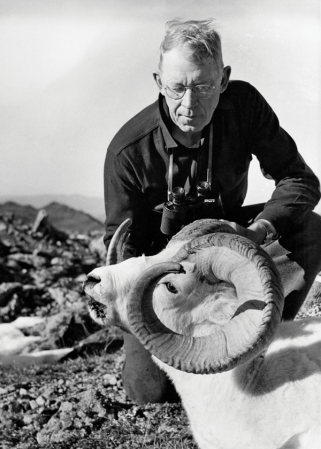

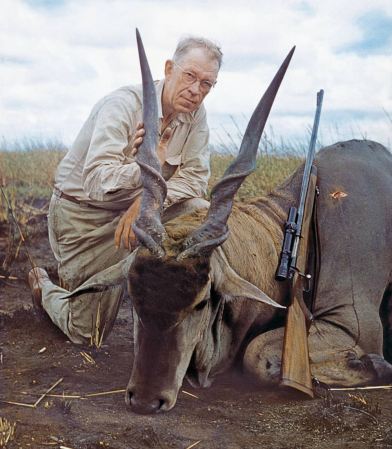

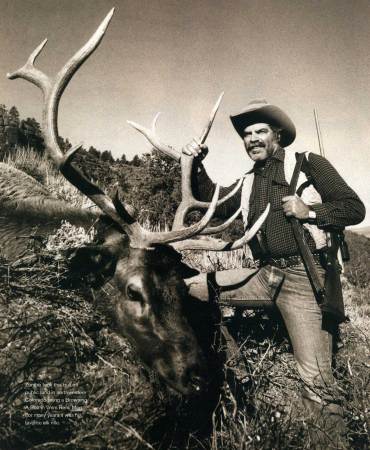

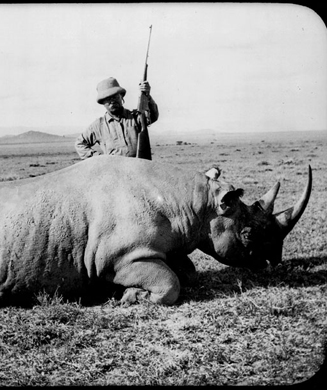

O’Connor allowed his adoring readers to follow him vicariously on hunts for all the species of North American big game. Sheep were his favorites and he managed a lifetime double grand slam (Rocky Mountain bighorn, desert bighorn, Dall and Stone sheep). His tales of safaris in Africa and tiger hunts in India are similarly popular.

O’Connor was a complex man. One of his good friends, Jim Rikhoff, suggests O’Connor was “a mixture of the sensitive and the sensible, of the ribald and reflective, of insight and inspiration, of instinct and intellect.”

Invariably, though, O’Connor exemplified “style.” We see this in his self-planned funeral, held in Lewiston, Idaho, after he died aboard ship en route home from a vacattion in Hawaii in 1978. His remains were cremated and scattered by Bradford over a mountain range inhabited by the sheep that had so captivated O’Connor throughout his life as a hunter. Similarly, as an author, he was unquestionably a masterful stylist, and the same held true in the natty way he dressed, his elevated sense of sportsmanship and many other aspects of his life.

All of these are a part of Jack O’Connor’s legacy, as is the body of outdoor writing included in more than two dozen books and hundreds of carefully crafted articles that he left to posterity. His compelling style places him at the forefront of America’s literature of the outdoors, and in the pages that follow, outdoor life readers can sample O’Connor’s craftsmanship through his excerpted works.