After spending weeks of scouting, prepping, and planning, you can’t wait for opening day to reap the rewards of the long weeks of toil. Unfortunately, when the season opens, the once-abundant and active deer herd has seemed to disappear. How can this be? You’ve put up trail cams, and maybe baited and used attracting scents, so where are those deer?

Research indicates that the deer herd may have gotten wise to sportsman. Investigation into the impacts of hunter activity and harvest on seasonal deer behavior began in 1988 with a study that focused on white-tailed deer in Missouri (Root et al.) and tracked both the movements of white-tailed deer and hunters before, during, and after the firearm season. Preseason and postseason hunter activity included archery seasons and small game hunting but not firearm hunting.

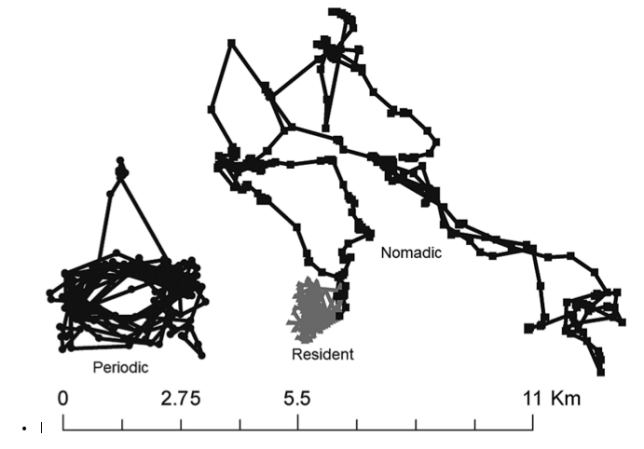

Researchers found, unsurprisingly, that hunter activity was much higher during firearm season than preseason and postseason periods. Equally unsurprising, as hunter activity increased, the movement of white-tailed deer increased as well. The increase of activity in the woods disrupted and altered typical deer movements for the duration of the firearms season. However, deer with portions of refuge areas in their home range (i.e. private lands/safe zones) did not exhibit increased activity as hunter movement increased. This suggests that the increase in hunter movement is influencing deer behavior as opposed to any seasonal behaviors like the rut. These findings were later replicated by VerCautern and Hygnstrom (1998). They, too, discovered that increase in hunter activity temporarily alter deer behavior.

A later study conducted by Kilpatrick and Lima (1999) investigated the effects of archery hunting on white-tailed deer movements in urban areas in coastal Connecticut. Their findings were similar to that of previous work: deer core areas and movements change during the hunting season when compared to preseason movements. More interestingly, the researchers found that daytime activity decreased and nighttime activity increased during the archery season (Kilpatrick and Lima, 1999). This change in from diurnal activity pattern to a crepuscular pattern (before dawn and after dusk) can significantly impact a sportsman chance at bagging a deer.

There are two key takeaways from this research. For starters, periodically checking trail cameras or scouting before the season may provide a false idea of where deer will hang out come hunting season. In order to get a better sense of how deer will react to human activity, it may pay off to be a bit more overt and disruptive when placing trail cameras and to scout more frequently and less stealthily, in order that deer get used to your presence in the field.

By increasing human activity before the beginning of the season, deer behavior may begin to change, providing a better picture of where they will be hanging out when the season opens.

The situation is tough for those of us who hunt public lands, because it’s difficult to predict how the deer movements may change with the large influx of sportsman. The best bet is to give your favorite spot a try, but if seems dead after the first day, it may be worthwhile to move your stand to a place with more activity by disrupted deer.

A solid strategy is to get a super-early start on opening day if you’re hunting a popular area, because the deer may be less active than usual during the daylight hours. The first hours of opening day may be your best chance at bagging a deer.

Sources:

Kilpatrick, H. J., and K. K Lima. 1999. Effects of archery hunting on movement and activity of female white-tailed deer in an urban landscape. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 27:433-440.

Root, B. G., R. K. Fritzell, and N. F. Giessman. 1988. Effects of intensive hunting on white-tailed deer movement. Wildlife Society Bulletin 16:145-151.

Vercauteren, K. C., and S. E. Hygnstrom. 1998. Effects of agricultural activities and hunting on home ranges of female white-tailed deer. The Journal of Wildlife Management 62:280-285.

Photograph by Natalie Krebs