As Ursus arctos horribilis outgrows the Montana backcountry, bears are moving into plains and river bottoms. This is Outdoor Life’s in-depth report on the population expansion. Is it time to once again hunt this symbol of the Western wild?

Mike Madel and I are driving north out of Choteau, Mont., in his Fish, Wildlife & Parks pickup, looking for trouble in the 2,500-square-mile area he patrols with his Karelian bear dog, Ursa. Madel has been trapping, darting, and bear-proofing his way to an understanding with grizzlies for 30 years now. He knows every rancher, butte, and drainage, and a lot of the bears. He keeps a list of the names and radio frequencies of the collars on local grizzlies’ necks by his right hand. I glance down and see that they have handles like Dex, Beenie, and Bonita. I look out the window, knowing the bears could be anywhere from the snow-capped Rockies on our left to the flat plains and grain fields on our right.

I’ve asked Madel to help me answer questions about these grizzlies: where they roam, how and why they get into trouble with humans, and whether it’s a good thing that their numbers seem to be expanding out of those snow-capped mountains beyond the window.

Put a tie on him and Madel could be a silver-templed CEO gracing the cover of Forbes. Thirty years working as a grizzly specialist for Montana FWP hasn’t turned him into the caricature of a mountain man I was hoping for. He’s all trimmed up and polite. When you go to Montana to spend time with a guy who spends time with bears, you expect him to be a character right out of a Russell Annabel story–hollow-eyed behind a tangled beard, big grizzly claws strung around his truck’s rearview mirror, a crazy knowledge of the ways of Ursus arctos horribilis (the horrible northern bear). And maybe some good scars from bad bears.

RETURN TO THE PRAIRIES

Madel knows that the fate of Montana’s grizzly bears requires as much boardroom acumen as it does backcountry savvy. Near the end of a celebrated career with FWP, he knows these unhunted grizzly populations are busting at their habitat seams and require more management than ever.

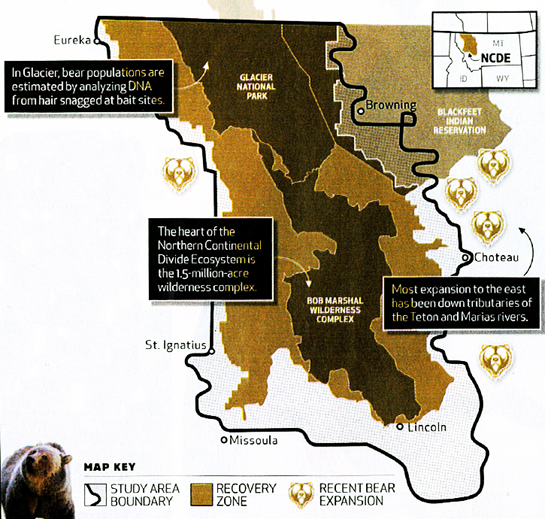

Here in northwestern Montana–what biologists call the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (NCDE)–the grizzly population has been increasing by about 3 percent per year for decades. Farther south, in and around Yellowstone National Park, griz numbers have stabilized.

The bears in both populations are now numerous enough that a lot of them are expanding out of the overcrowded Rocky Mountains like urbanites looking for elbow room in farm country. For these big bears, though, the expansion onto flat land is a return to their historic habitat. When Lewis and Clark came through Montana, they were harassed by grizzlies in river bottoms and breaks 250 miles east of the mountains.

In the wide-open areas of Montana and Wyoming, grizzlies are rediscovering that habitat, spending their days sleeping in ravines choked with willow and buffalo berry (a grizzly favorite) near houses, livestock, and crops. They spend their nights feeding–sometimes on the livestock and crops. This results in some touchy situations, such as when upland-bird hunters send their dogs into those ravines after pheasants or when ranchers go looking for missing calves.

Brad Carnahan found this out last spring. He has a ranch outside Big Piney, Wyo. The area has cottonwoods in the larger drainages, but mostly just sagebrush-covered hills. Last April, Carnahan was laid up with broken ribs after a horse threw him, so his wife and kids were looking after their calves. They found one dead and mostly consumed “two miles from the nearest tree.” They thought a black bear had killed it. But trail-camera photos showed it was a grizzly. “The local Wildlife Services trapper didn’t even know what to do with a grizzly,” says Carnahan. “My wife and kids were in the brush looking for lost calves in the dark. I’ll never let them do that again.”

Ranchers all over western Montana are going through the same reality check as bears expand beyond the backcountry habitat they were pushed to by encroaching civilization a century ago. It’s worth noting that the bears have been doing so well that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has been trying to remove them from the Endangered Species List in the Yellowstone region for years and are now preparing to recommend that bears in the northern ecosystem be delisted as well.

In the Yellowstone region, the bears were actually delisted in 2007, but in 2009 a lawsuit brought by a collection of environmental groups persuaded a judge to reverse the delisting because of fears the whitebark pine–whose cones high-country grizzlies rely on–might be in trouble.

Nevertheless, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar says he expects management of various grizzly populations to be turned over to the states by sometime in 2014. To facilitate this, the USFWS and other agencies have been gathering data to show the relationships between the bears and their various food sources.

Chris Servheen, the federal biologist in charge of grizzly recovery, says delisting won’t mean protections for the bears will be stripped away. “I say this because some groups claim that’s the case,” says Servheen. “It’s not true because the states would still have to maintain healthy populations, and they are committed to doing that. If they don’t, they’ll lose control of managing the bears.”

What’s contentious is that, as was the case when wolves were delisted, this will mean the states would likely use hunting as one of a suite of tools for maintaining grizzly numbers. This is the real reason behind some of the lawsuits by environmental groups.

HUNTING THE HUNTERS

Elk hunters have reason to hope for grizzly tags. A collaborative study by the Wildlife Conservation Society, the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and Montana FWP in 2004 indicated that some grizzlies in the Yellowstone ecosystem have learned that where there are elk hunters, there are gut piles to feed on. Researchers found that in September some grizzlies leave the protective boundaries of Yellowstone National Park to feed on carcass remains left by elk hunters, and when they can, they’ll even attempt to claim the entire kill.

On a few occasions the encounters have been bloody. In 2001, Tim Hilston went elk hunting in Montana and never came back. His body was discovered not far from a partially buried elk carcass. Investigators discovered evidence that Hilston was field dressing an elk he’d killed when a grizzly attacked him.

A more typical incident occurred last fall in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest. Hunters were doing an elk drive when a grizzly crashed out of the brush and tackled Weston Scott of Gillette, Wyo. The bear next came after Aaron Hughes, an Indiana resident. Hughes gunned down the bear at close range.

These are just a couple of grizzly encounters turned bad. According to Servheen, in 2011 alone there were 83 reported incidents in the northern Rockies of grizzlies charging people. Hunters were charged 31 times and hikers 29 times. Fourteen of the encounters resulted in human injuries, and two people were killed.

We’ve come to expect a certain amount of carnage on both sides in the Rockies each year, but with the grizzlies now repopulating the plains, the front line is moving to populated areas.

VIEW FROM DUPUYER

This led me to Madel. When a story gets overly political, it’s best to find someone on the ground to help cut through the confusion and nonsense of competing views and statistics. With grizzlies in the northern Rockies, Madel is that guy.

He points through his windshield, which like every windshield in the rural West is as cracked as shattered pond ice, and says, “Welcome to Dupuyer. Population 130.” He points to the bear-resistant fence surrounding the elementary school’s playground. “They built it after grizzlies were seen on Main Street.”

Madel pulls into a public park along Dupuyer Creek, a stream almost small enough to jump across that runs right through town. As we walk to the stream, he says, “We won’t have to go 100 yards before we’ll find grizzly tracks. Just east of us is where a bird hunter killed a charging bear.”

In 2009, Montana wildlife authorities reported that a man hunting pheasants with dogs was justified in self-defense when he shot a charging grizzly. Galen West jumped the bedded bear with three cubs at 20 feet. His third and fatal shot hit the bear between the eyes.

Sure enough there are grizzly tracks in the sand. People’s footprints and dog tracks from that morning are in some of the grizzly tracks–talk about a multi-use area. Madel kneels next to the tracks and says, “We’ve had some habituated bears here and we’ll have more in the future. But a lot has changed. At first the residents were up in arms. Now they’ve mostly learned to live with grizzlies. If agencies can delist the NCDE population and implement a restricted hunting season, management of bears will get better for two reasons. First, a hunting season will assist in reducing the number of bears frequenting ranch homes and communities. Secondly, hunters typically shoot the most visible, boldest bears that tend to come into conflict with people. Over time, the effects of hunting will help increase wariness in the bear population.”

To assist in maintaining this “behavioral wariness” of individual bears, Madel harasses them by using Ursa to chase habituated bears away from rural residences and campgrounds, sometimes in combination with exploding shotgun shells and other noise deterrents. He’ll also trap, radio-collar, and relocate them, and if necessary, he’ll euthanize repeat offenders. Meanwhile, local residents have learned to bear-proof their garbage, to give up on birdfeeders, to not leave dog food on their porches, and to move calving grounds away from bear travel corridors. The result has been fewer grizzlies causing trouble.

GRUDGING RESPECT

Dupuyer residents have now gone from concern to celebration. Each August the town now has Grizzly Day. Last year they had a pancake breakfast, bingo, and a parade.

“Today,” says Madel, “as the bears move east, each community is going through this same learning curve.”

Madel is on the forefront of that, too. He’d spent the evening before in one of the communities out on the plains talking about how to live with grizzlies. “I had 50 people show up for the talk,” he says. “Nearly the entire community. They asked questions until 11 o’clock.”

We leave town. Madel wants to show me where a few grizzlies have been up to no good. West of Dupuyer he picks up the radio collar frequency of a female that recently moved down from Glacier National Park. She’s bedded at the end of a piney foothill, right on the edge of the plains.

“Good place for her,” he says before heading south and stopping at a ranch along Smith Creek, where a 26-year-old male grizzly learned to open a sliding barn door last spring.

Madel says, “He’d just go right in and eat his fill of grain. The old bear had never been a problem before. But his teeth were worn to the gums. We set up a live trap and caught him. I hated to kill that old boy, but that’s bear control. His desperation made him dangerous.”

We head off again, this time to a ranch in the foothills west of Augusta. He mashes the brakes on a dirt road beside the Steinbach Ranch and jumps out, pulling on plastic gloves. Before I can get out he has a handful of grizzly scat.

“Fresh,” he says. “They’ll want this at the lab. They’ll be able to tell me what this bear has been eating.”

That’s important, as diet analysis can help differentiate problem bears from those feeding on natural foods. A few weeks earlier, a male grizzly preyed on seven newborn calves right below us. The bear carried the calf carcasses one by one and cached them in the brush.

“We had to kill him,” Madel says as a ranch hand pulls up on a four-wheeler. “It’s difficult to manage for a calf-killing grizzly bear when the entire Rocky Mountain Front is cattle country. So we’re having him stuffed. He’ll be mounted in the FWP office in Great Falls.”

“Oh, that bear,” says the ranch hand. “He was just getting started, but thanks to Mike he’ll be on display.”

We all shake hands and I ask about the grizzlies hanging out in the creek bottom likely within earshot of us.

He shrugs and says, “Just as long as they behave. When they don’t, we call Mike. Maybe some day we’ll be able to allow folks the opportunity to hunt grizzlies on our ranch.”

Madel is nodding. He has worked hard across his 2,500 square miles of turf to win the respect of the ranchers and a working acceptance of the grizzlies. He later explains that a few grizzly specialists have seen the ranchers as adversaries, and vice versa.

Madel is realistic. He realizes that both people and bears have to make compromises.

We visit more people who’ve dealt with problem grizzlies and hear stories about a local legend, the Falls Creek Bear that lived to 23 years in these parts and cost ranchers who knows how many thousands of dollars. Some of the bear tales have clearly grown into a local mythology, but in the stories there is awe and respect. No one says they wish the bears had all been trapped and shot out. But most wish to see grizzly bears managed by the state and to have conflicts with problem bears resolved swiftly.

After I part ways with Madel, he gets another call. A grizzly sow killed 70 sheep in two weeks, including 50 worth about $7,000 at one ranch. Most of the sheep in the area aren’t protected by electric fences because grizzlies haven’t been seen that far east since the country was settled. The grizzly front is ever moving.