Photo illustration by Vincet Soyez

Upland bird hunters without canine companionship are required to pull double duty–all the work of a man and his best friend. But the truth that you won’t read about in gun-dog magazines is that it is entirely possible to take limits of pheasants, quail, grouse, and partridge without a pointer or a flusher.

In some cases, you can be even more effective without a four-legged hunting partner. A good bird dog is a seamless extension of yourself. But a poorly trained dog will flush birds out of range, and chase deer and rabbits instead of roosters. And hard-mouthed hounds will treat your precious birds like chew toys, bringing mangled corpses to your hand–if they retrieve them at all.

Given the choice between a bad dog and no dog at all, you’re wise to leave Hellhound in his kennel and hunt alone. You’ll get birds, but you should expect to work like–wait for it–a dog.

That means you have to bust brush with the tenacity of a thorn-hardened Labrador. You have to course through thin cover with the endurance and commitment of a wide-ranging German shorthaired pointer. You have to hunt smart, anticipating where pressured birds will concentrate before they flush. Above all, it means using all your senses to retrieve and bag every bird that you bring down.

I have been a Lab guy for nearly two decades, and I derive a deep satisfaction from hunting behind my four-legged partners. My main reward isn’t shooting a long-tailed rooster, it’s watching my dog put all her training and instincts to work to put that pheasant in front of my gun.

But before I owned Baisha, then Hazel, and now Willow, and during some gaps between their presence in my life, I did plenty of bird hunting without a dog. In fact, many of us don’t own a hunting dog, or we’re between pups. But that doesn’t mean we should stop hunting birds. We just have to do it a little differently. We have to be the pointer, the flusher, and the hunter.

The best friend you can have when you don’t have man’s best friend is a best friend. You need another hardcore hunter who is committed to sharing the hard work and gamesmanship required to bag wild birds without the aid of a dog. A team of hunters can be even better than a pair, especially if you’re hunting wide country with lots of bird-holding cover.

But sometimes it’s hard to talk a buddy into joining you, so for every tactic that requires a team of pushers and blockers, there’s a trick for putting up birds when you’re all alone. I describe three different scenarios here, but like every hunting situation, the one you encounter in the field will be a hybrid of the ones I detail.

When you have tucked that final bird in your bag, may your buddy have the kindness to pat you on the head. And scratch you behind the ears. Good dog!

Photo illustration by Vincet Soyez

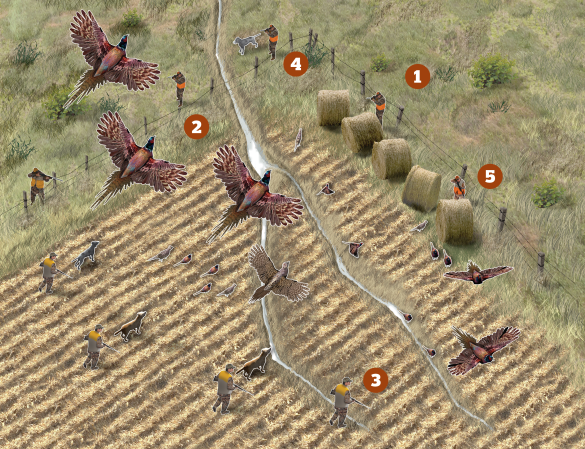

Scenario 1: The Fence-Line March

Upland birds love linear cover. Fence lines, tree rows, brushy shelterbelts, even rows of corn and wheat stubble all appeal to birds. Roosters, grouse, partridge, and quail will hole up in cover that’s dense enough to hide them, but thin enough to allow them to see danger approaching. Depending on the type of cover, expect birds to either flush out the sides as they are pressured, or to run to the end and flush as a chaotic burst of feathers and beaks.

Group: Blocking and Pushing

This is the ultimate block-and-push opportunity for a group of hunters. Post two buddies at the end of the cover, facing into the wind. Two other hunters should slowly walk the fence line, one on each side, occasionally stopping to unnerve the birds. Expect birds–especially grouse–to flush out the sides when the cover thins. Safety is paramount here; make sure everyone is wearing copious amounts of blaze orange, and knows and obeys safe shooting zone rules. Talk continuously. That not only rattles the birds, but it ensures everyone knows the locations of the hunters.

Solo: The Rooster Push

Linear cover can be hard for a single dogless hunter to work, because pressured birds–especially wild pheasants–will run to the end and then flush out of range before you can get to them. You can tip the odds in your favor if you hunt either just prior to or just after a storm. Heavy snow will encourage the birds to stay in cover. The walking-and-stopping technique will also flush birds in range, but the single best tactic is to hurry to the very end of the cover, being very mindful of muzzle control and your footing.

You don’t need to sprint, but a moderate jog or even a very fast walk will surprise birds that assumed they had more time. Some birds will flush at your approach, but even more will hunker down in the last feet of cover. Kick the brush, or wade into the briars, to flush the remaining birds at close range.

Scenario 2: The Brush Beat-Down

Whether it’s early-season ruffed grouse in shady aspen stands or late-winter roosters in dense cattails, upland birds love thick cover. Because few hunters have the gumption to wade into them, these sanctuaries protect birds from all but the most enthusiastic Labs, spaniels, and setters.

Group: Cattail Creepers

If you have a group of a half-dozen hunters, leave a pair of blockers on the periphery of the cover but send the remainder into the brush. The rules of this engagement dictate that all pushers must keep in a relatively straight line, and that they must maintain visual contact with their closest neighbors. It’s slow, slogging work, but you can extract roosters this way. The pushers shouldn’t expect to get many shots, but the blockers can have fast action once they pattern the flight paths of flushing birds.

Solo: Thicket Picking

Solo hunters can also work birds out of heavy brush, but they’ll have the best luck if they concentrate on smaller clumps of cover. A thicket about the size of a living room is perfect for a hunter on his own. Any bigger, and birds will tuck in the middle. Any smaller, and they’ll flush before you get in range.

First, beat the edges of the brush and see if hair-trigger birds will flush. If they don’t, stand on a rise above the brush and throw rocks, sticks, cow pies–anything big enough to make a racket and unsettle the birds–into the thicket, and be prepared for snap shots at wild-flushing birds.

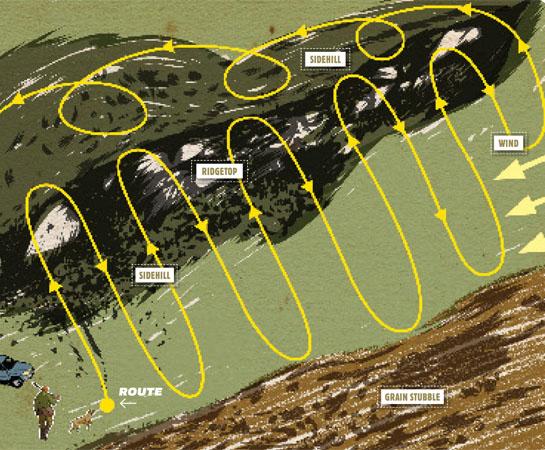

Scenario 3: The Pasture Play

Game birds are creatures of the uplands, the wide, open grasslands, CRP fields, and the stubble of harvested grain fields. The scale of these fields can intimidate a dogless hunter. How can you ever sweep all those acres? The good news is that you don’t have to. Instead, make efficient use of your walk through the fields. Zig and zag to bits of cover and any edge habitat, and concentrate on natural features like drainages and boulders, and manmade habitat such as abandoned farming implements, fence lines, and rock piles.

Group: The Corner Sweep

This is definitely a more-the-merrier enterprise. Walk as a group to the middle of the field, then work away from each other, heading toward the corners. The idea is that birds will concentrate on edge cover at the corners before they flush. As you walk, each hunter should concentrate on small scraps of cover. Stop periodically to listen for rustling birds.

Solo: Snow Days

If you’re hunting alone, wait for the right weather conditions. On bluebird days, birds will squirt out well in front of your approach. But immediately prior to, during, and just after a heavy snowfall, birds will hunker down in little pieces of cover. Stealth is important here. Park well away from the field, don’t slam the door, and be quiet as you walk to the edge of the field. Then listen. You may hear grouse drumming or roosters crowing. Watch. Look for bird tracks in the fresh snow.

As you hunt, mix up your pace and your direction of travel. You want to keep birds that would rather stay in cover guessing about whether or not you’ll hit their hiding place. Keep your shotgun at the ready and prepare for birds to flush directly under your boots.

The Ethics of Retrieval

If you’re used to hunting over a trained dog, then you probably rely on him to find your downed birds. When you don’t have a dog, that job falls to you.

Minnesota grouse hunter Tim Brandt and his buddies hunt the tangles of second-growth birch nearly every weekend before the leaves drop, and they don’t have a dog. They have lost only a handful of ruffs in their years of hunting because they are diligent about marking every bird that they shoot at.

“We have a couple of absolute rules,” says Brandt. “The first is that you don’t take low-percentage shots. If that bird is way out there and going away, we let it go. In heavy cover, you can’t afford to wound a bird and have it run on you.

“Our second rule is that if you shoot at a bird, you do not take your eyes off it until it either goes down or flies out of sight unharmed. If the bird goes down, the shooter keeps his eyes on the mark. He doesn’t move, and he doesn’t look away. He directs the other hunters to the spot until the bird is recovered.”