Over the last decade, as the rest of the West has been wringing its calloused hands over plummeting sage grouse populations, I’ve been quietly, happily, and productively hunting the big, open-country birds in what has seemed like my personal paradise.

For at least a dozen years, I’ve religiously greeted Sept. 1, the traditional grouse opener here in Montana, with a shotgun and an eager dog on the shimmering sagebrush sea outside my home in northeastern Montana. My twin boys’ first hunt a couple years ago was for sage grouse, which locals call “bombers” for their surprising heft and ponderous flight.

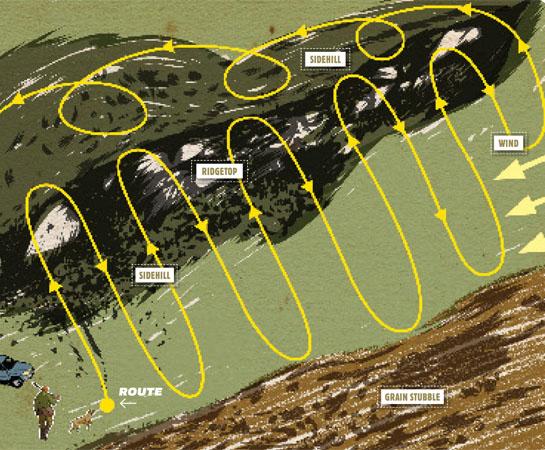

For most of those years, I never saw another hunter, and I was back at my pickup well before noon, a limit of bombers cooling in my vest, picking cactus thorns out of my dog’s paws on the dusty tailgate. I might return to the prairie once or twice more in a season, but I never killed more than a handful of grouse, though I would routinely flush several coveys in a hard day of hunting.

The author’s daughter and dog with a Montana sage grouse.

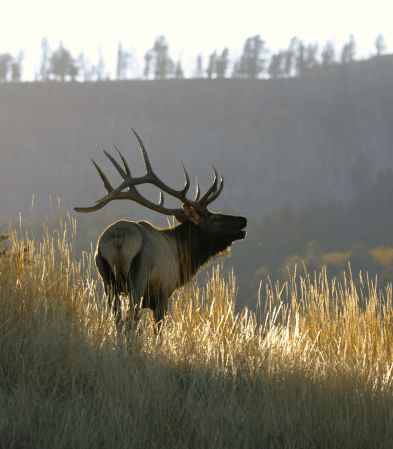

To me, the appeal of hunting bombers has never been about possessing them. It’s been the challenge of locating the birds in millions of acres of unbroken sagebrush–nearly all of it public–of finding buffalo skulls in scoured banks of prairie streams, and of seeing antelope sail the horizon like black-faced schooners. It’s been about engaging a native species that evolved with this remarkable landscape. And it’s been about the purity of solitude, of purposefully walking alone under the spreading sky.

As I’ve tuned in to the wider, anxious conversation about sage grouse across the West, I’ve been increasingly aware that my own experience with the birds is unusual. Across much of their range, especially in the arid Great Basin of Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, and eastern Oregon, grouse numbers have plummeted over the last 25 years. Drought, wildfire, overgrazing, cheatgrass incursions, disease, and energy development are all cited as reasons for the decline, and one by one, states around me have either restricted or ended hunting.

Habitat fragmentation is usually cited as the reason that bombers go away, but besides a few powerlines, fences, and cows where I hunt, I can’t imagine that the habitat has changed much since the Indians whose teepee rings I find lived here.

But a few years ago, I noticed that I had to walk a lot farther to find birds, and the coveys I put up seemed smaller in number, with more adults than juveniles. Two years ago, friends came to visit me with the express purpose of hunting bombers, and in two days of hard hunting we didn’t see a single bird.

On Sept. 1 last year I shot a limit of doves out on the prairie, but I didn’t flush a sage grouse. My boys have never shot a bomber on the wing, though they’ve walked miles of prime habitat and have picked cactus thorns out of their own paws.

Today, Montana’s Fish, Wildlife & Parks Commission may vote (See the update here) to close Montana’s sage grouse hunting season, citing documented long-term declines of male grouse on springtime dancing grounds. To me, it’s an unthinkable proposition, to end hunting for a species that, only a generation ago, was the most popular game bird in the state.

But then I recall my own experiences. I didn’t want to say anything a couple of years ago, after my first unsuccessful opening-day hunt, because I wanted to keep alive the myth of abundance here in Montana’s most intact grouse habitat. But something is wrong. The birds are declining. We need to figure it out and stop the slide.

Will suspending hunting help anyone figure out what’s wrong? I don’t know, but I do know that sage grouse have bigger problems than the harvest of a few hunters. And, I worry that once a hunting season for them closes, it’s unlikely to reopen, and sage grouse will lose one of their most passionate champions: the few of us who buy hunting licenses and trudge the prairie in search of them.

It breaks my heart to say this, but I would grudgingly trade a few years of hunting sage grouse so that my children, and their children, might have the opportunity that I’ve had.

But if FWP does close the season, they owe those of us who are so fond of bombers some real work to figure out what’s wrong.