This winter’s merciless conditions have brought reports of wildlife struggling to survive all across the country. The Minnesota DNR reluctantly rolled out an emergency feeding plan for its whitetails and a cold-stun kill in North Carolina devastated trout fishing prospects. And even though we’ve officially made it to spring, scientists say the effects from this winter will persist for months to come in the Great Lakes region.

The Great Lakes have experienced near-record ice cover this year, with 48 percent of the five lakes still covered in ice as of April 10. That figure is down from the high on March 6 when 92 percent of the five lake’s 90,000-plus square miles were choked with ice, according to The Atlantic Cities. In comparison, ice coverage of the Great Lakes maxed out at about 38 percent in 2013 and just 13 percent in 2012. (This NASA photo shows 80 percent ice coverage on Feb. 19.)

So what does all this ice mean for us? The sheer scale of ice coverage has already killed off thousands of ducks in the region, and cold water temperatures will likely push back spawning patterns for multiple fish species.

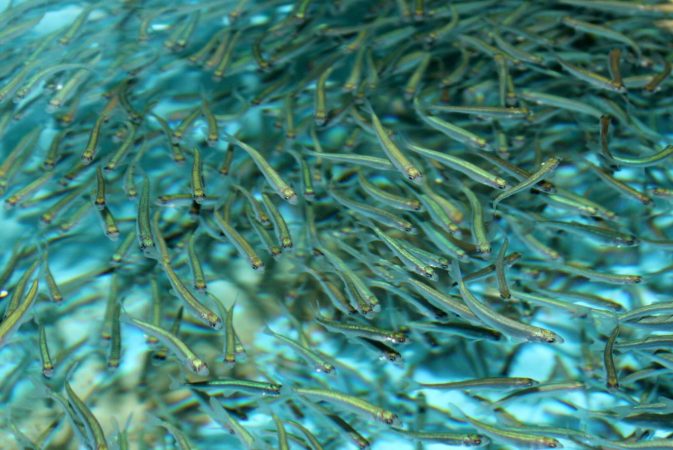

When the extensive ice cover prevented ducks from diving for minnows, the starving birds began to die in droves. Hundreds of carcasses began appearing in January along the Niagara River corridor in New York. The same phenomenon occurred in various locations across the Great Lakes, including the southern part of Lake Michigan and regions between Lake Erie and Lake Huron, reports the AP.

Many ducks tried to compensate by foraging for zebra mussels, which in turn posed toxicity problems. The invasive mussels filter toxins from surrounding water and transfer them up the food chain. Some birds were so desperate they even resorted to eating feathers.

One biologist with New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation personally counted 950 dead birds. “This is unprecedented,” Connie Adams told the AP last month. “Biologists who’ve worked here for 35 years have never seen anything like this. We’ve seen a decline in tens of thousands in our weekly waterfowl counts.”

Below the ice, fish are also feeling the lingering effects of winter. Warming water temperatures typically trigger migration movements to traditional spawning grounds, but experts expect a delay in this phenomenon as cold water remains. This delay will likely cause Northern Pike, lake sturgeon, steelhead, and rainbow trout to lay eggs later than normal. That could mean younger and weaker fish next winter and an overall impact stretching well beyond this season.

Despite all the gloom and doom suffered by our favorite species, there is a sliver of good news. Researchers expect water levels across the Great Lakes to rebound to higher levels than have been seen in years. As snow continues to melt and feed the lakes during the coming months, colder water could lower evaporation rates in the summer and fall. Too many consecutive years of low water lets some non-native plants take over, but a fresh surge of high water should help keep them in check and encourage biodiversity within the surrounding wetlands.