The key to good negotiation is good communication. With that, we’d like to invite James Cox Kennedy to an informal meeting to stop the war he’s waging on stream access in Montana. Our invitation is sincere, and we hope that he takes us up on it.

Here’s the scoop…

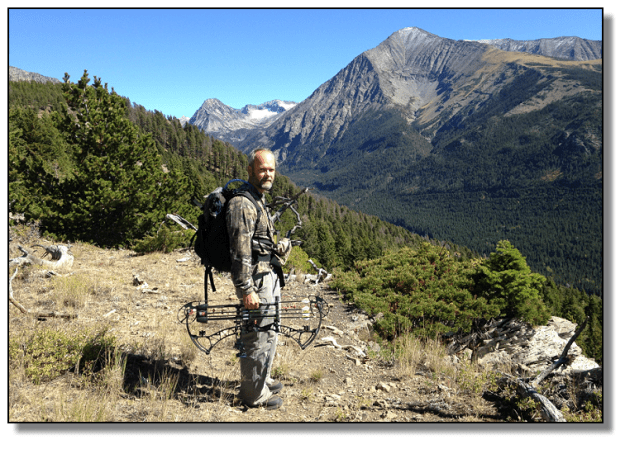

There’s a spot down on the Ruby River, just outside of Twin Bridges, Montana that’s become ground zero for Montana’s stream access battle. It’s a place I know well. I’ve driven past it for the last few years headed to my whitetail hunting spots. I’ve seen Booner bucks and gaudily clad pheasants in vast numbers on the ranch of James Cox Kennedy, an absentee landowner and multi-millionaire who seems intent on destroying Montana’s popular stream access law. The kicker is, if Kennedy has his way on the Ruby River, it could set a legal precedent for access in the rest of the state.

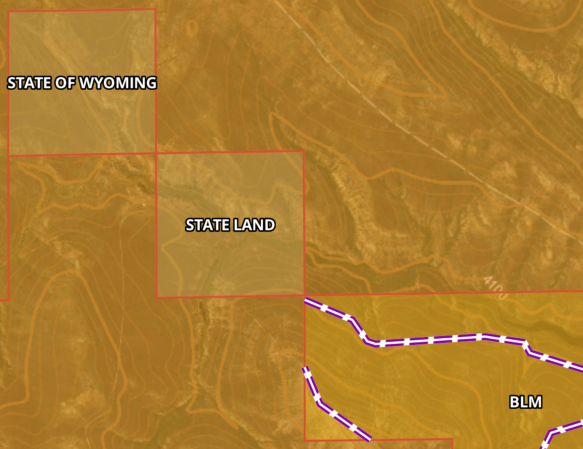

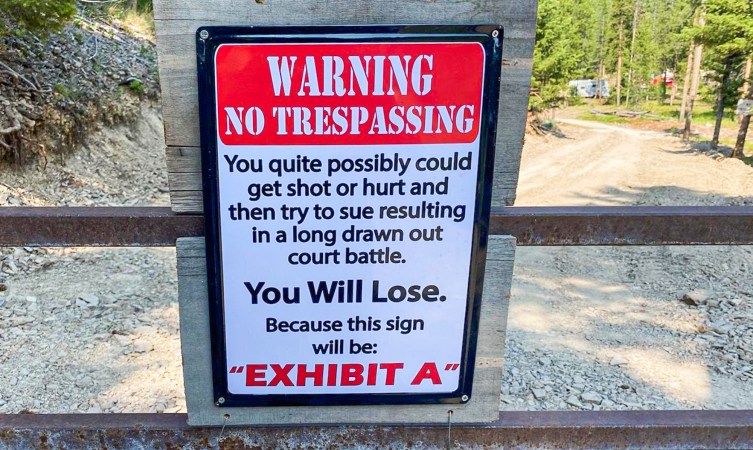

Using his seemingly unlimited funds to lobby, Kennedy tried to pass legislation that would have gutted the law rammed through the Montana legislature. He’s spent tens of thousands of dollars on court cases that, until now, have proved fruitless.

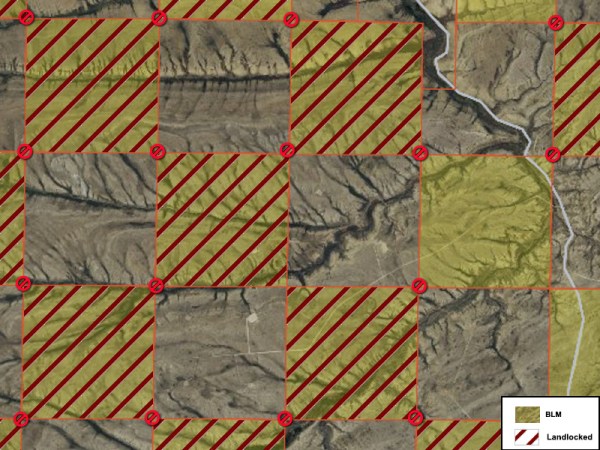

Mr. Kennedy hit the jackpot in late May when a judge ruled that the bridge going over Seyler Lane, which bisects his land, was placed there on a prescriptive easement (those are easements which say that if a road has been used for 5-7 years, then it becomes a public road, especially if public assets are used to maintain them. In the case of Seyler Lane, the bridge was built by the county, but the easement did not extend the 60 feet typical of public easements), and as such, no public access was historically proven by the defendants or required going forward. That decision will be appealed to Montana’s Supreme Court, according to the attorneys for the Public Land and Water Access Association, a group fighting the court case.

If the Supreme Court upholds the decision of the lower court, every bridge in Montana that has a prescriptive easement will go to court. It’s unknown how many prescriptive easements there are in Montana, and that’s part of the problem. Each bridge that is contested under that prescriptive easement clause will now have to go to court. That’s part of the game plan by those like Kennedy. They know that sportsmen are often unorganized and poorly funded. They’re simply trying to outspend the public.

To be fair, there’s no shoulder on Seyler Lane, and it would take a group like the Public Land and Water Access Association a couple days with volunteers and a few thousand bucks to fix up a parking area that was safe. While the law isn’t specific that improved parking areas, etc, are necessary when it comes to bridge access, it’s always better to work together than litigate. Seyler Lane would be a good candidate for a project that creates a safe access point, and creates a safe place to park. After all, nobody wants to get their rig side-swipped by a cattle truck.

Instead, this continual attack on Montana’s stream access law has cost lord knows how much money, and time, that could have been better spent working with landowners to find common sense solutions to the problems that really exist, like educating anglers on proper streamside etiquette, fighting noxious weeds and constructing livestock proof access points at bridges.

Because the truth is, landowners who do allow access have to deal with pretty poor behavior. Montana law says that so long as you stay within the high-water mark, you are legal. That’s not good enough for some. Anyone who’s fished in Montana has seen bad behavior. People sometimes cross pastures, leave gates open, and cause headaches for landowners. That needs to stop. But it shouldn’t automatically mean that the rights of the public should be eliminated because of bad behavior of a few.

We get it. Landowners greatly value their private land. But sportsmen greatly value our public access. Let’s not try to take anyone’s rights away in the courthouse. Instead, let’s figure out how each group can mitigate its impact on the other.

And that starts with having a conversation.