The recent militant takeover and arrests surrounding the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in eastern Oregon shone a national spotlight on one of the more obscure—but most important—pieces of America’s public land legacy: National Wildlife Refuges.

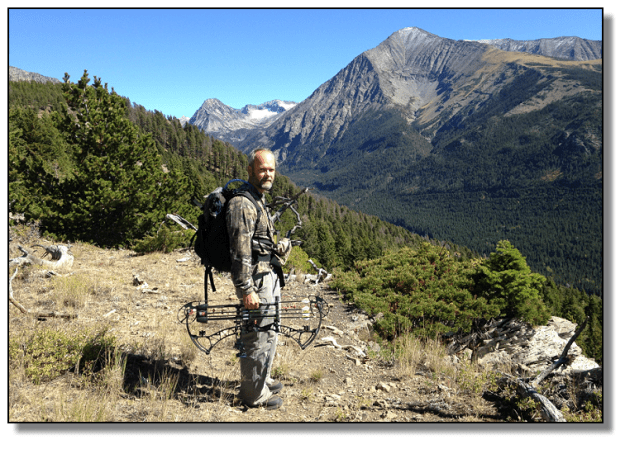

These refuges are particularly important for America’s outdoor families and the future of hunting and fishing. That is because providing access for quality hunting and fishing are among the top mandates of the National Wildlife Refuge System.

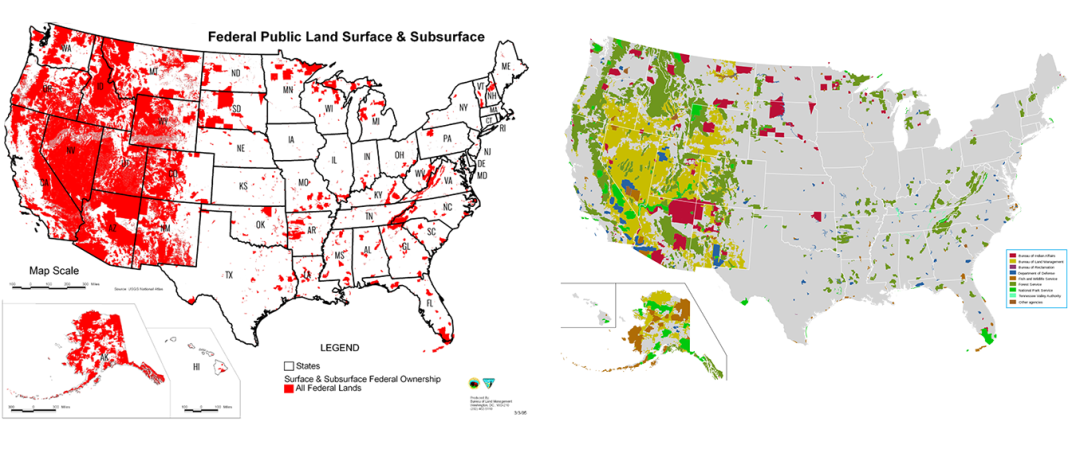

Basically, America’s public lands come in four categories. National wildlife refuges are the “little sister” of those categories, but punch way above their weight in terms of access. Here’s a recap of those agencies, and what sets refuges apart:

The Bureau of Land Management manages some 240 million acres, primarily arid rangelands of the American West. These are managed under a multiple-use mandate, which allows hunting, alongside other uses such as energy extraction, mining, and grazing.

The US Forest Service manages 193 million acres, most of it forested, much of it (with significant exceptions) is in the West and Northwest. Like the BLM, these lands are mostly open for hunting and fishing, and managed under a multiple-use mandate that includes watershed protection, timber production, and recreation.

The National Park Service manages 80 million acres under a stricter, more limited mandate. These are places like Grand Canyon and Yosemite, as well as smaller units such as battlefields and historic sites. NPS manages for preservation of natural resources within its boundaries. Hunting is strictly limited and generally not allowed, although some national parks, like Yellowstone, do offer excellent fishing.

Add to this mix the National Wildlife Refuge System. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manages some 560 units, or refuges, totaling 150 million acres. These range from tiny off-shore nesting colonies for seabirds to massive expanses of Alaskan bush.

President Theodore Roosevelt established the first National Wildlife Refuge in 1903 to protect Pelican Island off the coast of Florida from market hunters. (He established the Malheur refuge in Oregon a few years later to protect waterfowl and other migrants.)

Wildlife refuges are unique in that their mission is to promote wildlife and enjoyment of wildlife, not multiple-use. Other uses, like grazing or timber harvest, are allowed, but only if they serve an ecological purpose of improving habitat conditions.

Some 350 National Wildlife Refuges are open to hunting and 340 offer fishing. (Some refuges, like bird rookeries or urban refuges, are closed to hunting, but the vast majority of the acreage is open and managed for quality.)

Hunted big game includes everything from muskoxen to javelina. National wildlife refuges are particularly important for waterfowlers, as many are important stopping places along North America’s migration flyways.

In 1997, Congress redefined the mission of the National Wildlife Refuge System and codified refuges’ role for hunting and fishing, birding and wildlife viewing, and outdoor education.

Today, there is a red-hot debate about the role of public lands in the future of America. The militants at Malheur demanded that that 187,000-acre refuge be dismantled and turned over to the local county control and private hand.

Meanwhile, other organizations like the American Lands Council and the Mountain State Legal Foundation make a similar argument against public lands, in the court of law and in Congress and statehouses across the West. These folks argue that it’s unconstitutional for the federal government to hold and manage land in behalf the American people.

Meanwhile, sportsmen’s groups like Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, Trout Unlimited, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and others have redoubled their support for public lands.

Today, the No. 1 threat to the future of hunting and fishing is loss of access to quality habitat. America’s public lands are critical if we are to maintain our hunting and fishing traditions and freedoms. But of all those lands, national wildlife refuges have a particularly powerful role.

Photograph via Malheur Facebook page