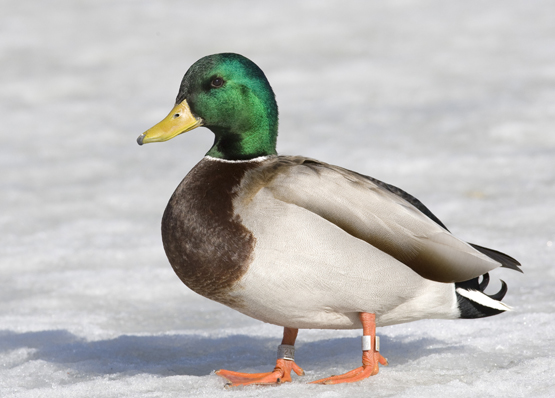

In late June 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) issued a ban on the importation of live birds, eggs, and raw wild waterfowl meat from Canada into the U.S. The ban was a response to a strain of avian influenza, known as HPAI, infecting domestic and wild birds across North America (it has been detected in more than 40 states and 10 provinces throughout the U.S., Canada, and Mexico this year). To slow the spread, APHIS is requiring U.S. hunters to cook any bird meat they intend to bring across the Canadian-U.S. border.

This rule has been in place for U.S. hunters returning from Mexico for years. Also, hunters wishing to mount trophy birds from Mexico must employ a USDA-licensed taxidermist so that the meat can be disposed of and the bird properly sterilized before it is returned to the hunter. U.S. hunters returning with taxidermy birds from Canada this fall will face the same requirements if the importation ban remains in place.

“Unprocessed avian products and byproducts originating from or transiting a restricted zone will not be permitted to enter the United States, including hunter-harvested meat,” APHIS said in a statement. “Non-fully finished avian hunting trophies must be consigned to an APHIS-approved taxidermy establishment.”

The importation ban only pertains to birds that fly through or are killed within the boundaries of specified control zones. These are areas that have a high incidence of bird flu. There is a continually updated map of the control zones within Canadian provinces to show hunters where these hot spots are located. Of course, the zones often change since waterfowl are migratory, which could make it difficult for hunters to judge if the birds they have killed are inside the parameters of the affected zones. And it will be virtually impossible for them to know if those birds flew through a control zone.

“I honestly think it’s pretty silly,” said Ryan Bassham, who has hunted Canada and Mexico extensively and helps hunters book bucket-list trips across the globe through his agency, Trophy Expeditions. “We know that waterfowl breed in the Prairie Pothole Region, lay their eggs, and then migrate south. They fly from Canada to the U.S. and some move on to Mexico. So, why is regulating the meat from waterfowl [necessary], when birds are already flying across the border?”

How to Cross the Border Legally with Harvested Waterfowl

Migratory bird law is confounding enough, but APHIS is adding another layer of confusion for hunters by telling them that if they cook their bird meat from a duck or goose that was killed inside a Canadian control zone, they are safe to cross back into the U.S. However, U.S. Fish and Wildlife (USFWS) requires that hunters leave a wing on all harvested waterfowl so that birds can be identified at the border. This is also a requirement when transporting any unprocessed waterfowl in the U.S.

It’s possible that a hunter could interpret the APHIS requirement of cooking waterfowl meat before crossing the border as a legal means to re-enter the U.S. with their harvest. But that’s not exactly true.

What APHIS doesn’t make clear—and it’s possible they are unaware of—is that the wing still needs to be on the bird even if you cook it to comply with the USFWS regulations. That means you would need to cook the bird meat with the wing still on it. If you crossed into the U.S. with just the cooked meat and no wing, that’s against the law and violates tenants of the Lacey Act.

“I worked for the Fish and Wildlife Service for 15 years, and I think what is happening is you have two federal agencies [the USFWS and USDA] not communicating with one another,” said Dr. Chris Nicolai, a biologist with Delta Waterfowl. “You’ve got the USDA that’s protecting agriculture. They’re used to livestock, dealing with eggs and chickens. Then you have the USFWS and they deal with bird identification and regulations. They don’t talk to each other ever.

“In order to satisfy both agencies in this case, I would have to smoke a goose with the wing attached, which I think I could do, though I don’t think most people would [eat] it with me. But the problem is [the USDA and USFWS] have different requirements that overlap zero. To be legal for one, you’re illegal for the other. It’s like pick your poison.”

Read Next: Wyoming Game and Fish Kills 1,200 Pheasants to Prevent an Avian Flu Outbreak

How Will the Bird Importation Ban Be Enforced?

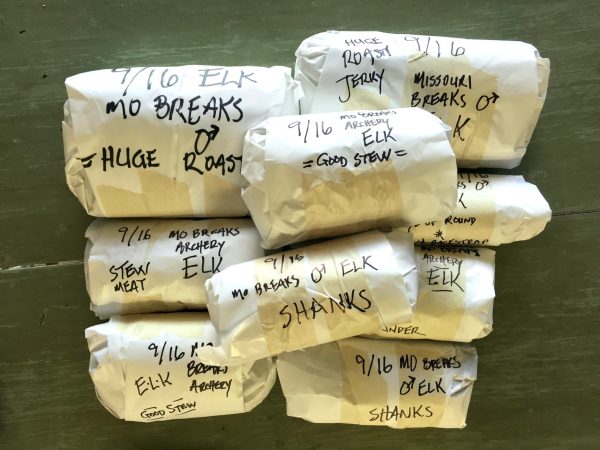

This isn’t the first time an import ban has impacted U.S. waterfowlers. In 2005 there was a global spread of H5N1 bird flu. When duck season opened in Canada that fall the ban on transporting infected birds into the U.S. remained in place. Though it didn’t last the entire season, scores of dead birds determined to have been shot in control zones had to be thrown away by hunters trying to re-enter the U.S.

“In 2005 I had a buddy from Alaska come with me to Canada on trip we had been planning for years,” Nicolai said. “We weren’t able to change our dates and just decided to go and deal with it as we were up there. When we went into Canada there were lines of dumpsters on the Canadian side full of birds. We saw people throwing birds in these dumpsters. There were rumors that some [U.S. politicians] saw this and got the whole thing shut down. By the time we crossed back into the U.S. we were able to bring all our birds back like normal.”

Maybe the most perplexing component of the restrictions is that they require hunters to know the exact location of where birds were harvested or what region they flew through before they were harvested. With control zones changing rapidly, it could be difficult to ascertain if birds were killed in an HPAI hot spot or not, especially if you are a U.S. hunter new to hunting in Canada. And it’s next to impossible to know if a bird flew through one of these zones unless it has a GPS affixed to it, which very few do. Moreover, there are no known studies that show import/export regulations stop the spread of avian influenza, according to a leading biologist of wildlife health and disease at the U.S. Geological Survey, the agency tasked with banding and collecting data on the movements of wild waterfowl.

“CBP officers are well-trained and highly skilled at processing travelers at the border,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection said in an emailed statement to Outdoor Life. “During the inspection process, if the CBP officer determines hunters are traveling with gamebirds harvested within the restricted areas, the hunter will be prohibited from bringing the birds into the United States. To help avoid possible penalties, travelers must declare all items obtained while outside the U.S.”

But in all reality, there’s no way for a customs agent to determine if a hunter was hunting in a control zone unless the hunter offers that information. It’s also possible that U.S. hunters may be ignorant of the import ban or the exact locations they were hunting, making it a real possibility for them to either show up at the border with infected raw meat which must be thrown out or cross the border illegally if they have unknowingly harvested birds from a control zone.

“Most of our clients are OK with eating what they can while they stay with us, and then we have the rest of the meat processed and donated to local farmers,” said Shelby Kirby, an outfitter who owns Black Sheep Waterfowl in Saskatchewan with her husband, Chris. “I wish there was a better alternative. It’s 2022 where technology is everywhere. Allow U.S. hunters to have their meat processed here and shipped back by a professional processor. I think that would be a simple solution to this ‘problem.’”