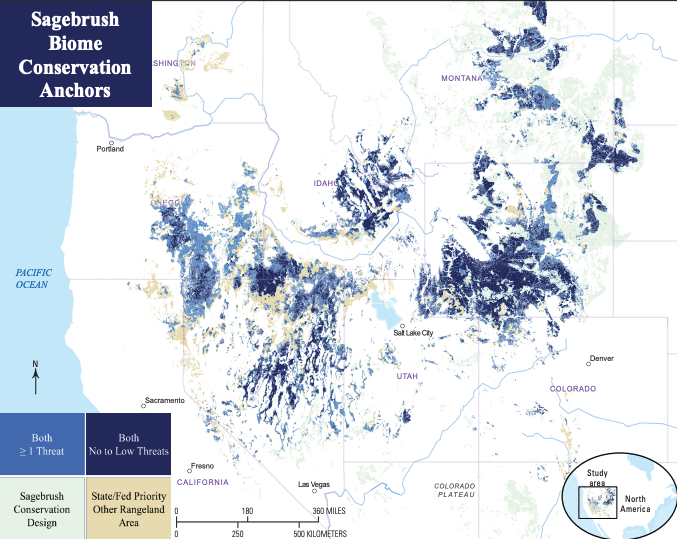

A report published last week offers a new approach for conserving and restoring sagebrush habitat in the American West. The Sagebrush Conservation Design provides a roadmap that land managers and decision makers can follow to proactively address the ecological threats facing the West’s disappearing sagebrush ecosystem. The biggest threats, according to the report, are wildfires and the encroachment of invasive, annual grasses across the landscape.

The report was a collaborative effort led by 21 scientists from 12 different agencies, universities, and non-governmental organizations, and it covers a vast region totaling more than 165 million acres in 13 states. Although it’s part of a larger, ongoing effort to conserve sagebrush in the West, the report also seeks to revolutionize this region-wide effort by giving researchers the ability to assess sagebrush habitats and track changes to these habitats over time.

Using satellite imagery and other remotely sensed data sources, researchers were able to look back to 2001 and see, among other things, that we’ve lost an average of 1.3 million acres of sagebrush annually over the last 20 years. This figure drives home the importance of conserving our remaining swaths of sagebrush, which are home to some of the most iconic wildlife species in the West.

“It’s all about detecting more of that annual change and trying to get more proactive rather than reactive,” says Lief Wiechman, one of the lead authors of the report and a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey’s land management research program. “By using satellite imagery, it provides us with the opportunity to track progress moving forward.”

To Wiechman’s point, another innovative piece of the Sagebrush Conservation Design is what researchers are calling the “Defend and Grow the Core” approach. The idea here is to focus on the intact core areas of healthy sagebrush habitat and then work outward to the more degraded areas in the region. While this might sound like an obvious strategy, lead author and U.S. Fish and Wildlife research scientist Kevin Doherty says it’s really the opposite of what we’ve been doing thus far.

“What’s been happening over time is this tendency called ‘action bias’, where you have these areas that are heavily degraded and we think we need to do something there,” Doherty explains. “But the problem is we’re not actually very good at reclaiming it. So, what we’re highlighting is: These are the anchor points where you can start your conservation strategy and work outwards, instead of going out to the most impacted areas first.”

What This Means for Wildlife and Hunters in the Sagebrush Sea

To determine how productive these anchor points are from a wildlife habitat perspective, researchers looked at five species that require large, healthy swaths of sagebrush to survive. Aside from pygmy rabbits, the other four “sagebrush obligate species” are birds, including sage thrashers, sagebrush sparrows, Brewer’s sparrows, and greater sage grouse—a priority species that has been the face of nearly every sagebrush conservation campaign in recent history. These large upland birds, which are beloved by wingshooters and birdwatchers alike, have seen a roughly 80 percent population decline across their range since 1965, and a nearly 40 percent decline since 2002, according to the USGS.

Upon closer inspection, researchers found that sage grouse habitat continues to shrink across the 13-state region. However, when they zoomed in specifically on the core sagebrush habitats, they saw that bird populations there have increased over the last 20 years.

“In the case of something like greater sage grouse, you’re almost getting 300 percent higher densities in these core areas compared to what you expect at random,” Doherty says. “And when you look at population trajectories over the last two decades in the core sagebrush areas, they actually increased—which is one of the few times that’s actually happened.”

Expanding this ideology to other species that weren’t included in the report, Doherty—who is a hunter himself—explains that what’s good for sage grouse will also benefit big game species like mule deer. That’s because areas with a healthy amount of native, perennial grasses provide significantly more forage than areas full of invasive, annual grasses like cheatgrass.

In this light, it’s easy to see how hunters and other wildlife enthusiasts can get behind efforts to restore sagebrush habitats in the West. But one thing that Wiechman and Doherty emphasize is that if we want these efforts to succeed, we’ll need every stakeholder group at the table—including private landowners and ranchers who depend on these habitats as working lands. Doherty compares this all-hands-on-deck mentality to the North American waterfowl management plan, which created a shared vision that has conserved tens of millions of wetland acres over the last 40 years.

“They realized in the 80s that they couldn’t do it alone,” Doherty says. “You need diverse partners, private landowners, local government, state government, conservation groups and federal agencies to come together to do it. We need everybody, is the bottom line.”