When Drew Hanes thinks about the worst disputes over blocked public access she’s encountered in her career, she recalls the time when her friends found themselves arguing with an angry Montana landowner instead of hunting antelope.

“In Montana we have a history of leasing BLM land to large ranches [for grazing],” says Hanes, the executive director for the Public Land Water Access Association. “My friends were hunting on this BLM land and the owner of the leases came out and said ‘I own this, you can’t be here.’”

Hanes’ friend pulled out a digital map to confirm that the group was standing on public land. But the landowner wasn’t swayed from his position that the group was trespassing. If anything, he was ready to stand his ground.

“The man had been drinking and had a gun,” Hanes tells Outdoor Life. “He said ‘I’m going to shoot you if you don’t get off my land.’”

Can landowners really block public access like this? The short answer is no, they can’t—or not legally, at least. That doesn’t stop a handful of bad apples from doing it anyway.

“Just like there are sportsmen and women who drive in a landowner’s field and make landowners genuinely mad at the hunting community, there are bad actors on the landowner side too that go out of their way to keep the public from accessing their lands,” Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership VP of western conservation Joel Webster tells Outdoor Life. “On both sides, those people are a minority, but they color the debate because their actions are fairly strident and they result in polarization.”

But the blocked access issue is especially visible in the Mountain West as more out-of-state landowners buy property that either sits adjacent to state and federal parcels or underlies a public road or trail, experts say. What has come with this influx is a lack of understanding—or, in some instances, a blatant disregard—for public access. Here are some of the most common ways a few over-the-line landowners obstruct access to public lands and waters, and what to do if you run into it.

What Does Blocked Public Access Look Like?

You might not recognize blocked public access when you first see it. While it’s best to take the “innocent until proven guilty” approach and assume all obstructions are legal and purposeful, further research might tell you otherwise. Examples of blocked public access include:

1. Locked gates across public roads or trails

This might be the most widespread, instantly recognizable example of blocked public access, Hanes tells Outdoor Life. She also notes that, at least in Montana, it’s illegal to obstruct a deeded public road in any way.

2. Strategically-parked cars or construction equipment

Big, immovable objects blocking public access pose a massive safety risk to anyone who either lives on private land past the obstruction or is recreating on public land. Firetrucks and ambulances can probably mow down a fence, but they don’t stand a chance against an excavator.

3. A big brush pile or a downed tree that is impossible to navigate around

In instances where the public trail goes over private land, stepping off the trail a certain distance to navigate around a downed tree could result in a trespassing citation.

4. A demand to sign in with the landowner first

This tactic is often used to erode undeeded, prescriptive easements (traditional public access that exists simply because the public has used it for an extended period). Signing in with the landowner means you’re seeking permission to use the trail, which helps the landowner prove that the public has abandoned the easement and therefore it no longer exists. (Don’t confuse this with lawful sign-ins required for voluntary hunter access programs on private lands.)

5. Trail cameras used to monitor humans, not game

While running cameras on public land is legal in most states, using them to conduct surveillance on humans often leads to harassment. It certainly did for one hunter in Michigan, whose treestand was intentionally damaged by another hunter on public land. The offending hunter was monitoring the victim’s activity on a trail camera and got angry when the hunter wouldn’t leave “his spot” alone.

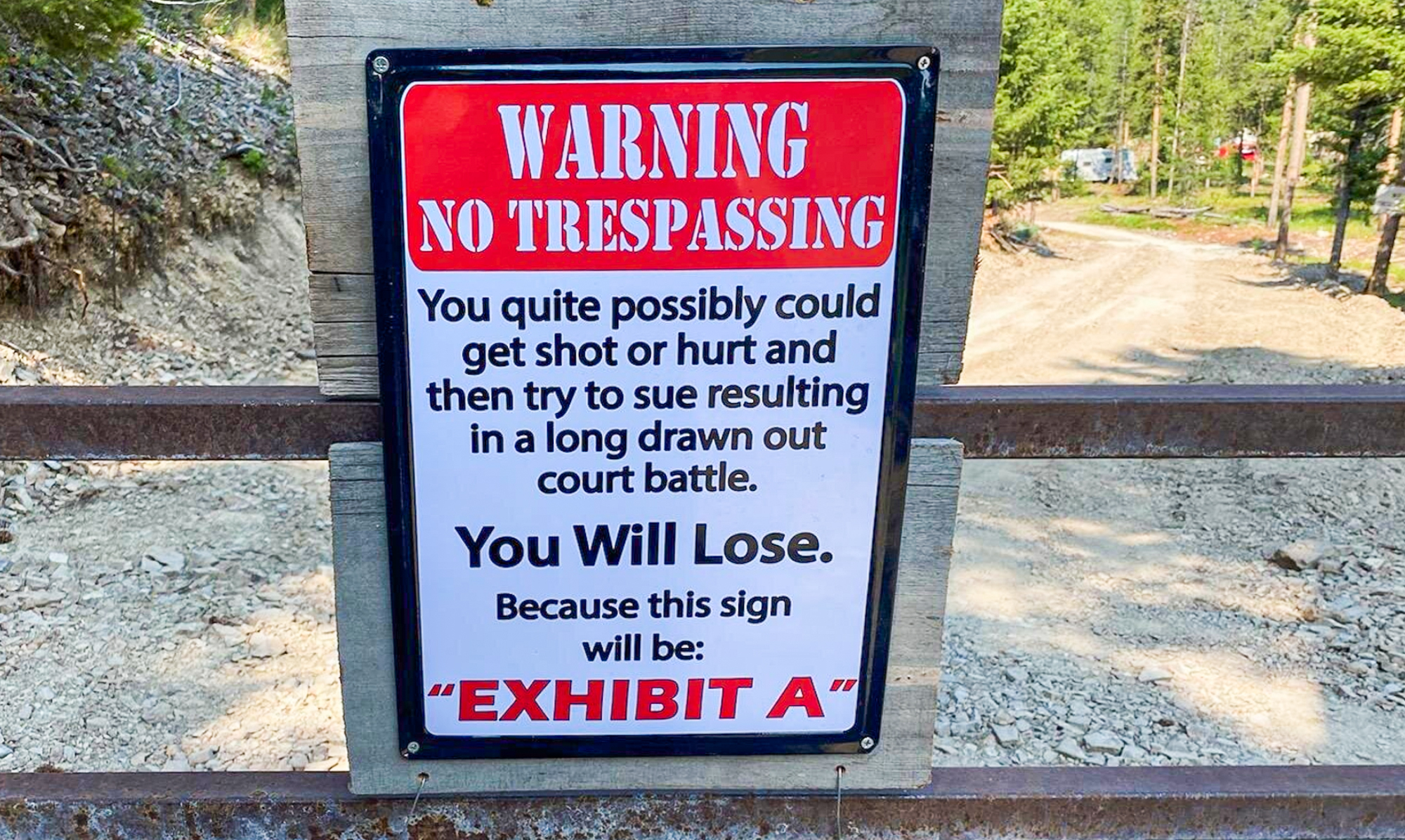

6. Misleading signs, including ones threatening legal action or physical violence

In one of Montana’s most infamous cases of blocked access, landowners posted a sign on a locked gate across Hughes Creek Road that read “Warning, No Trespassing: You quite possibly could get shot or hurt and then try to sue resulting in a long drawn out court battle. You will lose. Because this sign will be: ‘Exhibit A.’” (In fact, the Hughes Creek case involved several additional obstructions of access: the locked gate, brush piles, and an excavator parked across the public road.)

7. Confrontation with another person as a form of blocked access

Whether it’s a landowner or another hunter, someone might try to scare you away from public lands, waters, or roads. They could simply lie and tell you you’re trespassing on private land, or they could escalate to outright intimidation and threats, like the drunk rancher trying to run antelope hunters off his BLM lease.

You Found What You Think Is Blocked Public Access…Now What?

You don’t need to have all the answers immediately to address what looks like blocked public access, Hanes says. In most cases, it’s safer to avoid potential confrontation with an angry landowner or hunter (not to mention legal repercussions) by following these guidelines.

Know the Rules

The first step is to familiarize yourself with the laws in whatever state you’re hunting. State laws change frequently, so do a little research every year. In February, for example, Wyoming governor Mark Gordon signed a bill into law prohibiting anyone from falsely posting public land if a peace officer has already informed the person that land is public.

Other states already have regulations in place that support hunter access, even when it comes to private land. In North Dakota, for example, if you legally shoot game and that animal runs onto private land, you can legally retrieve it without landowner permission (as long as you don’t carry your gun or bow onto the land).

Document the Blocked Access

If you find what you suspect is deliberate obstruction of public access, record the details. That could be a locked gate, an intimidating sign, or something else fishy, says Backcountry Hunters and Anglers CEO Land Tawney.

“Record it with a cell phone or even just with pen and paper afterward so you remember the facts and where you were,” Tawney says. “Communication technology has increased so much. Everyone has a video camera in their pocket, everyone has a GPS in their pocket, so they know where they are.”

Documentation comes in handy for hunter harassment cases, like an instance in North Dakota when a landowner argued with a group of duck hunters for hours over where the property boundary was. One of the duck hunters recorded the whole interaction, which was later used in charging the landowner with hunter harassment, among other misdemeanors.

Make Your Phone Calls

If you have cell phone service, call the authorities, Hanes says. Consider saving phone numbers for various officials who have jurisdiction in the areas where you hunt or fish. This might come in handy if you have just enough service to make a call but not enough to search the Internet for a phone number.

“Go to an enforcement person who is in charge wherever you are, whether it is a county attorney or a state game warden, a Forest Service employee, whoever has jurisdiction,” she says. “Show them your documentation and show them what the issue is.”

Don’t expect the officials to know exactly what the state laws are, Hanes warns. They have a lot of regulations to keep track of, and may not have been approached about your specific issue before. This is why it’s important that you arm yourself with up-to-date information.

Depending on your unique access situation, you may need to approach a private attorney familiar with property and access law, or an organization like PLWA. But no matter what, it’s important to report your experience. Hanes estimates that over 90 percent of hunters who come across blocked public access or are otherwise harassed don’t report anything, leaving those situations unresolved and ripe for another hunter, angler, or public land user to walk right into.

Get Ready to Walk Away

Even if you know deep in your gut that the law is on your side, conflict is often not worth it, Tawney says.

“Physical barriers, sign-ins, surveillance cameras … all these things are some level of intimidation,” Tawney says. “These are always tense situations and folks need to do their best to be respectful, state the facts, share the legality that we foresee—but don’t escalate things.”

If any battles should be fought over blocked public access, they’re best fought in a court of law.

“At PLWA, we play the long game, and sometimes it takes years,” Hanes says. “We get precedence established so that we don’t have to risk someone getting shot at every single gate. We want to get the gate taken down and show why this is so important.”

Longterm Solutions to Blocked Public Access

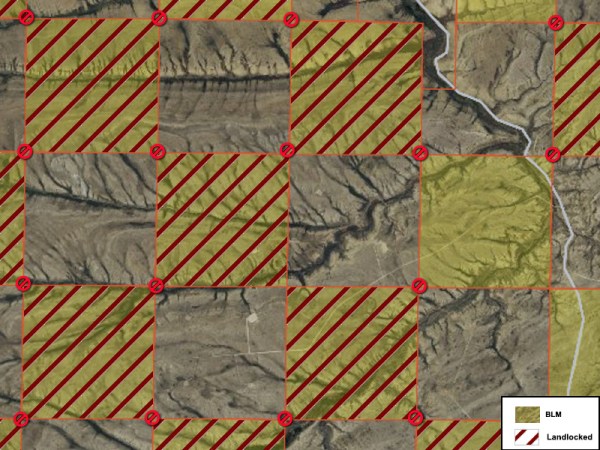

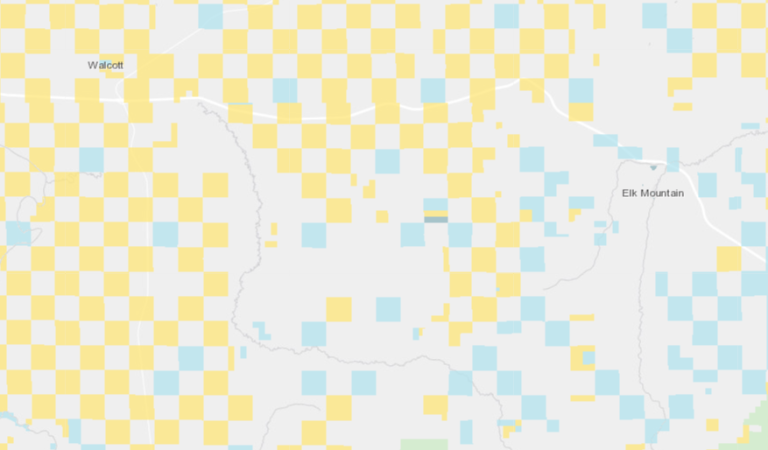

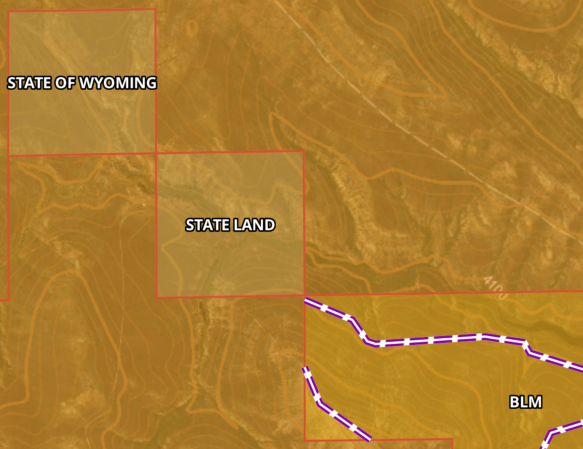

Contested public access is nothing new, but solutions to the issue are evolving, onX Hunt senior access advocacy manager Lisa Nichols tells Outdoor Life. The rise in popularity of onX allows hunters and landowners to see the same boundaries, easements, and access points.

“For anyone who is using onX, whether it’s a landowner or a recreator … it gets everyone on the same page—especially for new landowners in the West,” Nichols says. “Seeing where the public is allowed or not allowed really helps avoid conflict.”

Another major boon to protecting public access is currently being implemented at the federal level. In April 2022, President Biden signed the Modernizing Access to our Public Lands Act, also known as the MAPLand Act, into law. The Department of the Interior, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers are now required to digitize and publish GIS data on close to 100,000 easements that are currently only filed on paper and stored in dusty field office basements across the country.

The act requires that agencies digitize all those easements by 2026, and so far, they’re about halfway there, Webster says. Once the project is complete, that data will populate apps like onX and countless more access opportunities will resurface, including a few that might currently be blocked.

…and What Not to Do

When navigating an instance of blocked public access, there are a few negative responses that experts say should be avoided at all costs:

- Don’t plow through the fence or rip down the sign. This simply invites more conflict. Channel that energy into documenting the obstruction instead for future legal action.

- If a landowner is blocking a public road or trail, don’t trespass on their property to get to public land. Trespassing won’t do you any favors when you need local law enforcement and government on your side to legally resolve the issue. Besides, trespassing is a great way to get arrested.

- Don’t assume all private landowners oppose public access. Don’t let one bad experience with one private landowner ruin your relationship with others. Neighboring landowners might be able to help you document other access obstructions. If all landowners thought all public-land hunters were trespassing assholes, Tawney points out, voluntary hunter access programs wouldn’t exist.

Above all, you can’t help fix the problem for the next public land user if you’re lying in a hospital bed or, worse, dead. That’s why Hanes’ friends ultimately decided not to risk life and limb for their right to hunt antelope on the BLM land.

Read Next: “I’d Have to Bury You Out Here.” The New Mexico Stream Access Battle Is Far From Over

“They finally said ‘We apologize, we must be lost. We’re so sorry.’ And they got up and left,” she recalls. “That was the right thing to do. When you’re standing there and someone has a gun, you probably go on your way that day. Then you bring those issues to organizations to do the research and handle it in a different way. It’s not worth getting hurt over.”