SAVE YOUR PENNIES. Keep detailed spreadsheets. Crunch the numbers. Diversify your portfolio. Hire a consultant to manage your assets. Discuss short- and long-term strategies. Plan for the worst and hope for the best.

We’re not talking about retirement planning. This is how many hunters are tackling the big-game draw system in many Western states. Because there’s a growing boil on the backside of hunting in the West. It’s called point creep, and it’s not pretty.

Point creep is the spawn of the preference point system. Generally speaking—because every Western state is different—every year that a hunter applies for a limited-draw tag and doesn’t get it, they can buy a preference point. Think of these as a loyalty program: The more you buy, the more likely you are to draw a tag. Sometimes a hunter can buy a point without applying, paying anywhere from $5 to $150. The theory behind point systems is that if a hunter waits patiently and buys points every year, they’ll eventually draw the primo tag in a choice unit. That may have been feasible when point systems were established, but it’s not always the reality anymore, thanks to point creep.

Point creep occurs when the number of hunters applying for a tag increases faster than available tags. Therefore, the number of points needed to draw a particular tag “creeps” upward. Over time, as more hunters compete for the same number of coveted tags, an individual’s odds are diluted. Despite careful planning and high fees, hunters can wait decades to see a return on their investment. When they do finally draw that bighorn sheep tag or trophy mule deer unit, they might be too old to handle the punishing backcountry trip it demands. Others may never draw.

To be clear, this phenomenon occurs only in some hunting units. Point creep is not a universal truth of limited-draw tags. But as more hunters grow frustrated with a system that feels inaccessible and unrewarding, they are beginning to wonder: Are long-shot tags a false promise from state agencies to make a few million extra bucks? Can you beat point creep? (Spoiler: You can’t.) Is this system sustainable, or is it time for a change?

Playing the Game

At 42, Robert Hanneman lives in Montana and works two jobs. He’s a firefighter who piles on double shifts in the off-season just so he can hunt all fall with his family. His 14-year-old has already killed four bull elk. His 16-year-old is on track to complete the Super Ten.

Nearly 20 years ago, before he started a family, Hanneman started applying for a Wyoming moose tag. The third year he applied, he had three points and was within one or two years of getting the tag—or so he thought. Today, with 19 points, he still hasn’t drawn that tag, and he’s still at least two years out, based on his calculations. “I don’t know if I’ll ever draw,” he says, noting that his odds are dismal given that Wyoming allocates only 20 percent of its moose tags to nonresidents.

To make matters worse, he must deal with point creepers. Wyoming allows hunters to buy a point each year, even if they don’t intend to hunt in the fall. So even if all the hunters ahead of Hanneman drew the tag and he moved forward in the queue, someone who has been sitting on the sidelines buying points could decide to jump in line ahead of him with their 20 points.

“The worst possible thing you can do is die with the most points on the table. Once you draw the tag, hunt your guts out.”

—Robert Hanneman

Let’s take Unit 2 as an example. In 2010, 233 residents and 12 non-residents applied for an antlered moose tag there. Three residents drew with 15 preference points apiece; the lone lucky nonresident who drew had 11. In 2020, 241 resident and 19 nonresident preference point holders applied for an antlered moose tag there. Again, three residents and one nonresident drew. No one had fewer than 21 points. The remaining 238 resident applicants in 2020 were entered into a random drawing for the one remaining tag in the unit.

Hunters can thank Colorado for kicking off the preference point concept more than 20 years ago. The state has a true preference point system, meaning that whoever has the most points gets to hunt the area they want to—as long as tags are available.

A huge problem—the –problem—with preference points, as Hanne-man’s situation illustrates, is that hunters are paying into a system that may never pay out to them. It doesn’t seem to deter many hunters, especially once they’re invested with a few points. And if you don’t participate, you’re guaranteed never to draw the tag you want. Nearly all Western states implement a version of the point system, and each is maddeningly different.

For instance, Utah puts 50 percent of nonresidents in the preference point system and has more tag categories than ski resorts. For nonresidents, Montana employs preference points and uses a random draw with bonus points you can buy each year—then it squares your bonus points. If this all sounds clear as mud, you are not alone. That’s why Hanneman also works a second job: as a hunt consultant. In 2005, he ran his own consulting business; in 2012, he went to work for the consulting service at Huntin’ Fool. His job is to explain the outrageously complicated regulations and point systems to hunters.

“When speaking to clients, I say, ‘The worst possible thing you can do is die with the most points on the table,’” Hanneman says. “Once you draw the tag…treat it like every other hunt and hunt your guts out.”

Enlisting the services of a guide to help navigate harsh terrain or pursue an unfamiliar species is nothing new to hunters. That some folks must employ help just to apply for a tag borders on the absurd.

Deep Camo Pockets

In 1970, the U.S. had the same number of hunting license holders as in 2018: right around 15.6 million, according to the best available license data. Adjusting for inflation, hunters in 1970 spent $677.7 million on hunting license fees, tags, and more. In 2018, we spent $872.2 million—nearly $200 million more. Where are we spending all that?

Let’s consider Everett Headley. He’s a 38-year-old outdoor writer and educator who is married with no kids. He hunts anywhere he can get a tag. In 2020, he estimates he applied in 18 states, spending around $3,000 on licenses and points. The man draws enough tags to keep him hunting around the West, and he buys lots of points too.

Then there’s Justin Spring, director of big-game records at the Boone and Crockett Club. He’s 39, with a young family, and he’s been putting in for tags and points in various states since he started his full-time job 12 years ago. One year, he sat down and crunched the numbers, only to realize that he and his wife had spent around $8,000 on tags and points. Now with a budget in place, his family spends between $2,500 and $3,000 each year.

Spring and Headley aren’t the jet-setting type. Buying tags and points is simply how they spend money, and hunting is how they spend their vacation days. When he doesn’t draw a tag, Spring shrugs off the loss as a donation.

“It’s gambling that’s going to conservation,” he says. “I know that I’m most likely not going to draw, and I’m OK with that. At the end of the day, we’re doing this to help wildlife and fund conservation. It’s a trophy hunt, and you’re not saving money by hunting trophies.”

“I find it hard to put into words why I don’t like the point system, but I am convinced I don’t want to play the game.”

—Mike Stolt

In this context, hunting sounds too complicated and, in a way, anti-thetical to the democratic principles of the North American model of wildlife conservation. That model, among other things, is supposed to ensure that hunters have “access to wildlife without regard for wealth, prestige, or land ownership.”

Then I spoke with Mike Stolt. Stolt flew F-15E Strike Eagles in the Air Force. Now he flies commercial jets and calls Texas home. He spends his falls taking wounded veterans into the Idaho wilderness to chase elk and mule deer. (In Idaho, many tags are first come, first served for nonresidents. In 2021, applicants swamped online queues to buy tags that sold out in hours.) His passion is bowhunting elk in Colorado, and he goes whenever his schedule allows.

“I find it hard to put into words why I don’t like the point system, but I am convinced I don’t want to play the game,” says Stolt, who bowhunts the same over-the–counter unit every year he can. It’s the one he used to hunt with his dad. He realizes there are “better” units in the state but doesn’t much care. “When I hunt, I like to keep it as primitive and simple as possible. I know my place so well.”

Therein lies one of the upsides of our wildlife management system. There are opportunities for hunters out there, and you don’t have to wait years or spend thousands on points to enjoy them.

Milking Nonresident Fees

Keep in mind that the pitfalls of point systems mainly affect nonresident hunters. State agencies typically manage wildlife for the residents of that state and allocate the majority of tags accordingly. They charge nonresidents way more for a chance to fill the same tags, which is why nonresidents are the cash cows for Western game agencies. For instance, I live in Montana and pay $20 for an elk tag. A nonresident must fork over some $900 to hunt the same ridge as me.

Those agencies also make a pickup-truck load more money from point systems than OTC tags alone. Nonresident hunters accounted for $43.6 million, or 77 percent, of Wyoming Game and Fish’s budget in 2020. The preference point system contributed nearly $12.2 million of that. This was more than all elk license revenue, and double the preference point revenue from 2014. As the number of nonresident applications climb, so too does revenue.

Another way states grow revenue is by incentivizing hunters to keep buying points. If a hunter fails to apply or buy a preference point for two years in a row in Wyoming, they lose their accumulated points. Hanneman’s Wyoming moose point costs him $150 each year. Residents pay $7 for the same privilege. It’s another way states can keep wringing money out of applicants. Who wants to abandon $300 after two years of putting in—let alone the $2,850 Hanneman has invested over nearly two decades?

Crunching the Numbers

Mike Street lives to hunt big mule deer, both in his home state of Colorado and just to the north, in Wyoming. As an electrical engineer with a doctorate in physics, he approaches point systems with an analytical mind. He used sophisticated software to help determine the sweet spot for successfully drawing a trophy mule deer tag in Colorado. His takeaway? Nonresident applicants should look at hunts that take just over four points to draw. The bad news? Everyone above and below that threshold is screwed. His research found that point creep is very real and that building points in Colorado is “unfavorable” for drawing a once-in-a-lifetime tag.

“The more points you have as a nonresident, the worse your odds and tag allocations get,” he says.

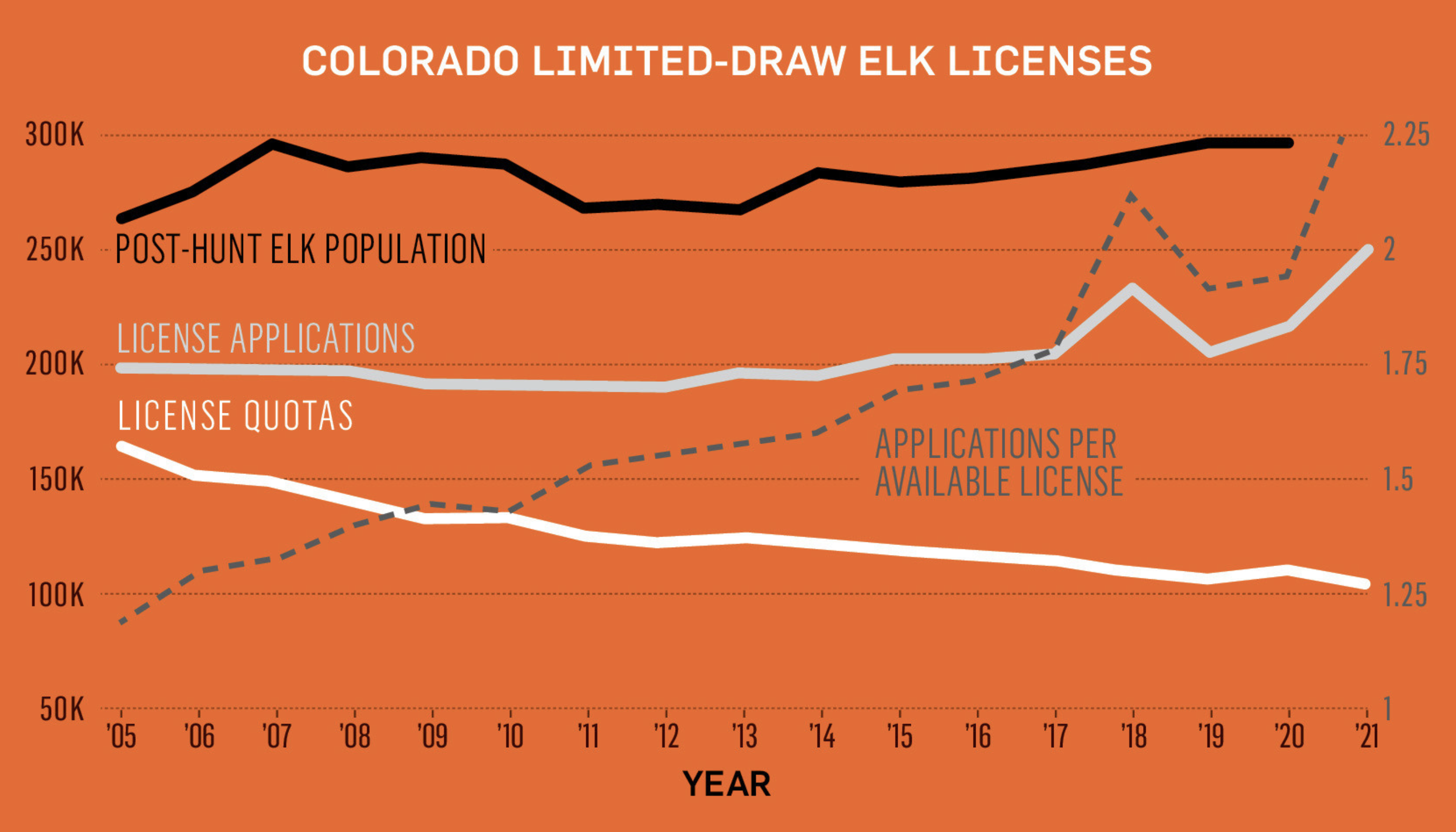

And the future is especially dim for hunters applying to high-demand areas. Street found that nonresident applications in Colorado have increased by roughly 30 percent since 2015, meaning that folks who want to draw-hunt Colorado with no points might be out of luck until the wave of applicants dies down—which may be never. Despite numbers that suggest some eager applicants may never get their desired hunting opportunities, Street understands the need to balance hunting opportunities with a resource like mule deer.

“The point system is something you have to have—to a degree. You have to do something to balance supply and demand. The point system lets me plan future hunts. But there are so many people buying points and not even putting in—that’s when people get pissed.”

While Street does love to bide his time for choice mule deer tags, he has no problem hunting every year in Colorado. “It’s become harder to get the higher-quality tags, but there are plenty of hunts available at zero preference points for residents.” This is an important takeaway: As a resident, he can still go hunting every year. He may not hunt in the “best” area, but he’s still deer hunting.

Another hunter who knows his way around a spreadsheet is Randy Newberg. This CPA-turned-hunting-personality is a regular Midwestern guy. He’s posted more than a few YouTube videos on point systems wherein he breaks down numerous Western states. The results are telling, if not depressing.

Take Utah, where hunters can buy preference points. Newberg emphasizes that hunters must look at the actual number of hunters in a state’s point pool to get a realistic idea of what they are up against. Utah issued 274 elk tags for nonresidents in 2020, and the state claimed 17,958 nonresident applicants, Newberg explains. That made for odds of a little more than 1.5 percent. But more than 16,000 hunters simply bought points, so the actual odds of success dropped to 0.8 percent. To put it another way, there are 125 years’ worth of applicants in the nonresident Utah elk pool.

Myth, Reality, and the Future of Point Creep

As long as we are willing to pony up the cash for points, state agencies will use it to keep the lights on. The systems will likely get more complicated, but they’re not going away any time soon. Are they perfect? Hardly. Is there room for improvement? Always.

As you read this, Colorado Parks and Wildlife is putting together focus groups of resident and nonresident hunters, outfitters, and other stakeholders “to strike a balance between predictability of drawing a license, fairness, and providing a chance for anyone to draw a highly desirable license in his or her lifetime,” says Travis Duncan, a CPW public information officer. Public comment (and you know there will be plenty) will follow. Hunters might see changes as soon as 2023.

But the last thing state wildlife agencies want or need to do is eliminate a revenue source, which point systems provide. States can’t just eliminate preference points when hunters have invested so much in the system. Agencies can’t refund everyone’s money—they’d go bankrupt. If there were an easy fix for the point creep issue, managers would implement it. For now, though, it’s all duct tape and bubble gum until an acceptable solution is found.

We aren’t the same hunters our grandparents were. Today we have more money to spend on tags, points, gear, and gas—and more desire to hold out for the opportunity to shoot a large animal. The rise in point buyers alone suggests a large segment of hunters may be more into feeding their egos than filling their freezers. Are we willing to spend days and dollars sifting through hundreds of pages of regulations and draw stats to find the ultimate tag, or do we just want to hunt? That’s another thing Hanneman likes to remind his clients.

“Whatever you do, don’t be afraid to burn your points and go hunting,” he says. “Points don’t equal antlers, and I’d always rather pack deer than points.”

This story originally ran in the Deer issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.