The first three deer to come by me were ridge-flat regulars—I’d seen them before, both on trail camera and in person. The lead whitetail, a piebald button buck, was a welcome sight, even though I had cursed him so many times these past few weeks. At first a curiosity, the little buck had become something of a nuisance during bow season due to his ravenous appetite for the apples that covered the leaves near my stone-wall ground stand and his proclivity for busting every good setup.

But I never thought that the cool-looking little deer would be capable of running the gauntlet of hunters during general firearms season, so it was good to see him in this final hour of the final day. A doe and an I’d-probably-shoot-him-on-any-other-day 8-pointer followed, each glowering at their backtrails as they picked their way toward my food plots several hundred yards down the hill.

It’s always exciting to see deer on the last day of the season, but missing was any rush of adrenaline—for good reason. There was another deer around, or at least I hoped that he was still around. It was a buck the likes of which I’d waited my entire life to take. It’s why I never even thought to flick the safety off on the 8-point.

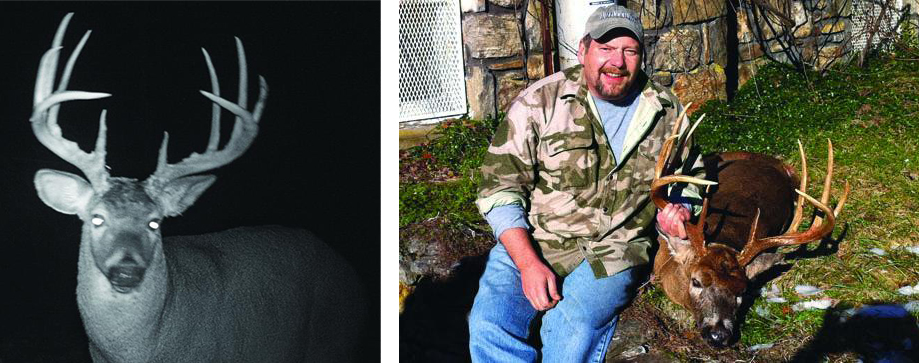

That other buck had haunted my trail camera for a solid month and left me day- (and night) dreaming of killing him. In a land of dinks and almost-shooters, this was a bona fide stud. Hell, he’d qualify as such in Kansas. He was a perfect 10-point, so symmetrical that I thought my buddies were playing some sort of cruel practical joke on me when I first saw the photos. What would he score? Who knew? Who cared? I surely didn’t. But what I did know was that I’d never seen a larger rack on any buck on my family’s property in all the years of living there—nor had anyone else who hunted our little patch of New England deer woods.

I barely had time to wonder why those first three deer might be so unnerved when a single thought screamed in my brain…

“Buck!”

That simple word and a thin smile were pretty much the only signs of acknowledgement Dad had been capable of during Thanksgiving dinner two weeks earlier. In addition to some snapshots I’d taken of our deer camp, I had downloaded a couple dozen trail-camera photos to my phone to show him in the hope that seeing a photo of that buck on his property might ignite a spark of recognition in his brain—that he’d somehow come back to me even if only for a moment or two. You see, that’s mostly what we—families of Alzheimer’s sufferers—pray for. Something. Anything. A glimpse or a glint, some little part of the old Dad would do. And I got that little gift.

If there’s a more insidious disease than Alzheimer’s, I certainly can’t conceive of it. What other ailment kills a host’s loved ones years before actually killing the host? And make no mistake, my family (no different from any other Alzheimer’s family) has been dying in fits and starts for more than a decade. No one is capable of standing by helplessly while watching a father, a spouse, or a dear friend fight their own mind without losing a part of themselves. Even harder is watching a once-brilliant engineer, capable of taking anything apart and putting it back together, struggle for hours on end to solve simple word-search puzzles.

Truth be known, Dad wasn’t really a deer nut—never shot one, actually—but he did hunt with me each season and both tolerated and nurtured my addiction to chasing whitetails. He bought me my first deer-hunting coat when I was 15, and he lugged an extension ladder a half mile through the woods to build my first treestand. We drove three hours through a ferocious ice storm in his brown Buick LeSabre one Thanksgiving night just because I told him that the bowhunting the next morning would be incredible after such a weather event. He gave me my first sip of whiskey after I spent too many hours in that same stand during a blizzard. Even though it’s been years since Dad has hunted, he always liked to hear my stories of deer missed or deer killed and other adventures at our family’s little hunting camp—or at least it seemed as if he did.

A Deer for the Ages

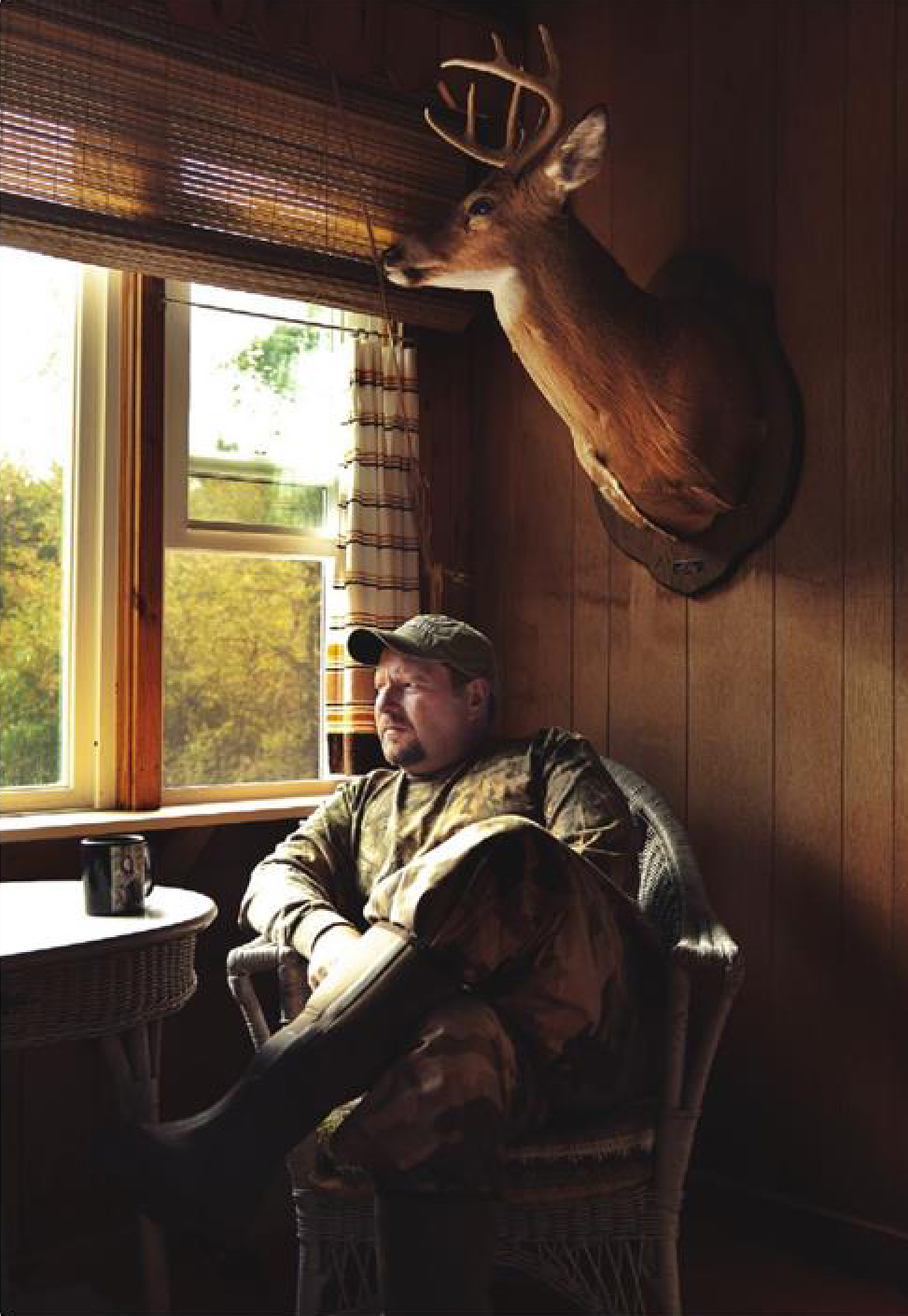

Somehow, the trail-camera photo of the huge buck brought that particular Dad back to me, if only for a moment before he went away again. But it was enough—I knew that he knew. And so it was that after 1 ½ months of frustration during bow season, and much of the same during the firearms hunt, I felt the sort of motivation I remember feeling two decades ago, when he and I used to sit within sight of each other in the deer woods and I wished for a buck to walk by so that I could do my dad proud. I decided that I needed to show Dad one more photo—the one in which I’m holding that buck’s rack in my hands in front of the camp where he and I had spent the greatest days of our lives.

“Buck! It’s Him”

Just five minutes or so after the last of the three deer walked out of sight, I finally spotted the reason for their preoccupation. Even at 80 yards there was no mistaking him—that magnificent rack, burly body, and gait of dominance. It was the one I had come to think of as Dad’s deer. Whether it was the cautiousness of his years or my impatience, I still can’t be sure, but the damned buck seemed not to move no matter how hard I wished him to—neither would he give me a broadside shot. This stasis lasted long minutes and was physically draining. I didn’t dare stare him directly in the eyes, but I didn’t dare look away either. When he’d finally take a noiseless step, he’d stop to scrutinize the frozen woods, and it seemed his intensity bored right into me. He closed from 80 to 50 yards but I still hadn’t heard a footfall on the frost-brittle leaves. He still would not turn broadside.

Okay, I’ll shoot you dead-on facing me if I need to, you big bastard, I thought. It’s not ideal, but if you get too close I’m going to shoot. I’m not gonna blow this one.

As if eavesdropping on my conversation with myself, the buck somehow cut the distance to 35 yards, though I swear I didn’t see him take a step. And then he turned. Using my knee as a solid rest, I snicked the safety forward, put the shotgun’s bead on his chest, and squeezed it off. The big buck kicked high with his rear legs—a good thing—before tearing off for parts unknown—a very bad thing. Then the woods became still again. I sat there in agony listening for many soundless minutes and fighting off the urge to run to the place where the buck last stood. As much as I wished to see him lying there dead in the light skiff of snow, to run my hands along his main beams, I feared more the agonizing what-ifs.

What if he was still alive and I pushed him to a nearby hunter, who shot him?

What if he was still alive and I pushed him into some far-off thicket, never to be recovered?

What if I missed him completely?

What if I wouldn’t be able to show Dad that single, all-revealing photograph?

Diminishing daylight made the decision to give the buck time a bit easier. Judging from his size on the trail camera, I’d need help getting him out of the woods anyway. I’d go back to camp, have a beer or two to calm down, and make a few phone calls.

To the Woodpile

Three torment-filled hours later, I finally received a return call.

“You got him,” said a familiar voice on the other end of the line, not in the form of a question, but rather a statement. “We’re all at a Christmas party, but give me 20 minutes and I’ll be there.” I never got the chance to respond before the phone clicked. The cavalry was on its way. If anyone could help me find the buck, it was my friend Rich Hamilton.

In typical subdued fashion, Rich walked through the door, asked to hear the story, then wasted no time heading out the door again. Although he’d not been there with me, he took the lead in our search for blood.

“Well, this ain’t worth a sh&$,” he said when the beam of his flashlight hit a single drop on the snow. “Not worth a sh&$ at all.”

And he was right. Even with the skiff of snow on the ground, it was difficult to find a second drop. The hoped-for salvation of all sunset shooters—a blood trail a blind man could follow—was not revealing itself. My heart sank.

“Well, he fell here,” Rich deadpanned, now following the running tracks in the windblown spots of snow. “Fell here, too.”

Our flashlight beams fell on the giant rack simultaneously. He hadn’t gone more than 50 yards.

“Look at that giant son of a bitch,” Rich said. “Oh…my…God.”

I’d never before seen a more magnificent sight. Dad’s deer had come to rest in a boggy thicket amid a jungle of briars, his rack seemingly floating 5 feet above the ground. Under the moonlight, we could see the faint lights of camp and billowing woodsmoke pouring from the chimney. We unashamedly hugged and shouted, then struggled to get the big deer onto a dry hummock for field dressing. In all honesty, I was of no help.

“Here, hold the flashlight,” Rich said after my first header into the muck. “I need to gut this deer. I want to gut this deer.”

An hour later, and too tired to move him any farther, much less hang him up, Rich and I wrestled the buck to the top of the basement woodpile. We stepped back a few feet to simply stare at the deer for the first time in full light—at a complete loss for words.

After Rich left, I stood and stared some more—long into the night—just me with the buck and thoughts of a hunting season incomparable and unreproducible. And of my Dad.

By the next day, everyone who cared to hear the story, and some who didn’t, came by the house. After a while, 10 of us—each grabbing an antler, a hoof, a leg, or the tail—carried the buck outside and into the sunshine. Embarrassingly unprepared for a photo session, I handed my camera phone to one of the kids and asked him to click off a few pictures. I really only needed one.

Instead of fading with time, my exhilaration seemed to grow in the days that followed. I told the story countless dozens of times and emailed photos to friends around the country, but it wouldn’t be until Christmas Day, two weeks later, that I would see Mom and Dad.

Merry Christmas

“He’s not having such a good day today,” my mom said when she hugged me at the front door. “Just sit with him for a while.”

And I did. I told him our story and showed him our buck, but his eyes remained focused on the word-search puzzle book in his lap, as he haltingly circled letters—the sound of my voice either unheard or completely foreign.

“Hey, Grandpa!”

Somehow, my daughter, Amy, has always been able to garner Dad’s instant attention, and she did again on Christmas Day.

“Merry Christmas,” Dad said as Amy hugged him in his chair, word-search book falling to the floor. The hours Mom spent rehearsing those two words with him had paid off. Tears welled in his eyes as he smiled at a face he fought his own brain to recognize.

I picked up his book as they hugged, Amy trying in vain to engage Dad in conversation but getting no response. Glancing down at the crumpled page, my eyes focused on three circled letters: D-O-E.

My Dad was back, if only for a moment or two, before he was gone again.