When Bruce Hoseck had the opportunity to buy a pair of captive whitetails—a buck and a young doe—some 20 years ago, he didn’t hesitate to stroke a check. Hoseck already had a taxidermy studio at his Winona County farm in rural southeastern Minnesota, and the way he figured it, the pen-raised deer added a bit of whimsy to his operation. He kept the pair in a 2-acre pen, but soon the little herd grew, and Hoseck expanded his fence, using quarter-sawn telephone poles as posts to enclose 14 acres. He did a modest business charging people to come in and shoot the older bucks that he fed a diet of commercial deer pellets.

“I never grew any monsters,” Hoseck says, “but I’d be happy if someone wanted to pay $1,500 for a 140-class buck. They’d just shoot them right there in the pen.”

Only Hoseck’s deer didn’t always stay in the pen. A section of the perimeter fence slumped lower than state standards allowed, and part of it ran along the edge of a woods. Sometimes big storms would drop limbs on the fence and allow the deer to escape. He always got them back, but he didn’t always get them back right away. In 2007, a hunter killed a 10-point whitetail on a neighboring farm with an ear tag that traced back to Hoseck’s operation. The escapee was never reported to authorities.

Despite his inadequate fence, Hoseck routinely passed annual facility inspections by the Minnesota Board of Animal Health. Then in 2017, a 3-year-old buck died inside the pen. The Board of Animal Health, which regulates captive-cervid (cervids are members of the deer family, which includes elk and moose) operations in the state, requires all game-farm mortalities to be tested for disease, and Hoseck submitted the head of the young buck for testing.

The board notified him that the buck tested positive for chronic wasting disease (CWD). Now he had a choice to make: quarantine his herd (no transfers of deer for five years, plus annual testing) or depopulate it.

“I’m not getting any younger. I just turned 70, and my knees are going,” Hoseck says. “So I decided to get rid of my deer. Government sharpshooters came in and killed them. All seven tested positive for CWD.”

Doomsday for Deer

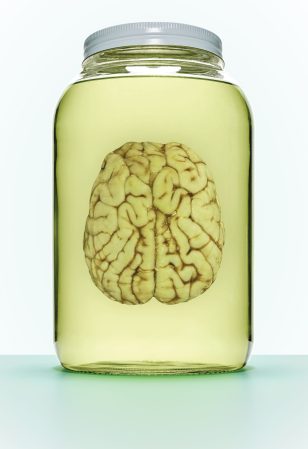

Wildlife professionals describe CWD as the most important disease threatening North American cervids. It’s a brain-eating plague perpetuated by a rogue protein that resides in the lymph and nervous tissues of infected cervids. Those proteins, called prions, can be passed on to other deer, and can even reside in the clay-based soil of an infected site for years. During this time, they can be picked up by new hosts. While there is no current evidence that CWD can be transmitted to humans, it belongs to the family of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) that includes bovine spongiform encephalopathy (“mad cow disease”). Most TSE experts as well as the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that humans not eat venison from CWD-infected deer, out of an abundance of caution. This concern has left thousands of hunters in hundreds of CWD-positive counties wondering whether or not they should feed meat from harvested deer and elk to their families.

There is no cure for chronic wasting disease, which is always fatal. It kills its host by causing lesions to form in the brain. For now, it can’t be detected until its final, degenerative stages—and can’t be confirmed until the animal dies—so, it can be passed from deer to deer before it’s detected. It was first identified in captive mule deer in the late 1960s in a university research station in Colorado, and it’s been closely associated with game farms ever since, partly because captive cervids live in such close proximity to each other that transmission is especially likely, but also because deer that die on game farms are more likely to be tested than their wild counterparts.

But it’s also true that many game farmers engage in a lively trade, buying and selling captive deer and moving potentially infected animals to new areas.

News of a 100 percent CWD-infected captive deer herd sent shock waves through Minnesota’s deer-hunting community last year, especially after the history of escapes from Hoseck’s deer farm was reported. The area’s proximity to Wisconsin—just across the Mississippi River—further intensified concern over CWD, which was detected in wild whitetails there in 2002 and has been spreading across the Badger State ever since.

While there’s no direct evidence connecting Hoseck’s diseased deer to detection of CWD in wild deer, the DNR imposed a three-year surveillance zone around Hoseck’s farm, liberalizing harvest rules and requiring hunters to submit the heads of deer they kill to be tested for the disease.

Managing chronic wasting disease in general, but Hoseck’s case in particular, reveals a deep regulatory divide between state agencies charged with inspecting captive deer and elk facilities and those that manage wild cervids. And those divides extend to the constituencies they serve. Game-farm regulators talk about vaccinations, devalued breeding stock, and disease mitigation. Wildlife managers talk about statistical probabilities, declines in hunting participation, and disease containment.

But game farmers and wildlife managers alike say that CWD has the ability to drastically alter our relationship with deer if left unchecked. The question going forward is how the two groups and their constituents will, and won’t, work to slow its spread.

The Deniers

Todd Froberg, a landowner assistance specialist with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources based in nearby Rochester, is tasked with talking about CWD with hunters and landowners in the region. He encourages increased harvests of wild deer to reduce densities, and he promotes testing of all hunter-killed whitetails in the region. The state needs hundreds of samples in order to detect the disease and establish prevalence, which is an estimate of the percentage of diseased animals in the overall population. But Froberg has noticed a disturbing trend, which he calls CWD fatigue, that is frustrating efforts to learn more about the disease and stop its spread.

The year after detection, there’s widespread concern, Froberg says. “Everybody wants to do their part, whether that’s learning about CWD or submitting samples for testing. Year two, there’s less interest. After that, fatigue turns to denial. On the one hand, there’s a common misperception—which seems to be growing—that CWD has always been here, so there’s nothing to worry about. On the other side, people say now that it’s here, we can’t do anything to stop it, so why do we have to kill all the deer? And that’s when participation [in CWD surveillance efforts] all but stops.”

Ambivalence about CWD isn’t unique to southeast Minnesota. Across the country, as the brain-wasting disease pops up in new areas and the prevalence rate climbs across wide swaths of CWD-infected landscapes, America’s deer hunters have largely gone numb to the consequences of the disease.

Some even claim it’s nothing to worry about.

A number of influential wildlife consultants, many of whom have connections to the captive-cervid industry, distributed “An Open Letter to Texas Deer Hunters” last summer, in which they raised doubts about everything from the nature of CWD (it’s a syndrome, not a disease, they said) to state wildlife managers’ response, and stated that CWD simply isn’t a “widespread disease (syndrome) of any biological significance.” They further noted that CWD creates a “huge regulatory and financial burden” on deer breeders and that deer farmers shouldn’t be required to report diseased animals.

This CWD-denial tendency has gained ground among some hunters too. Last summer, after Missouri banned bait for deer in counties with or adjacent to CWD detection in order to minimize the density of potentially infected animals, Jay Gregory, host of The Wild Outdoors TV show, posted a video in which he implied that state agencies are conspiring with insurance companies to reduce deer populations, using CWD as a rationale for aggressive harvest objectives. Gregory referred to CWD researchers as “idiots.” Rocker and TV personality Ted Nugent has joined the chorus of denial, saying CWD concerns are “a scam” on Joe Rogan’s wildly popular podcast. He’s also claimed that “more deer are killed in Michigan every year by feral dogs than all the deer ever worldwide by CWD.”

Brian Murphy isn’t surprised at the lack of civil discourse or consensus about CWD, even by hunters whose traditions and livelihoods could be affected by the disease.

“CWD is the perfect storm to erode trust in authorities and create a deeper divide,” says Murphy, a certified wildlife biologist and CEO of the Quality Deer Management Association. “In this era of fake news and ‘alternative facts,’ there’s general hostility toward experts, and we’ve become conditioned to believe only the facts that fit our narrative. Besides, the science around CWD isn’t altogether clear. Add to the mix that government agencies are mandating changes in our behavior, and it’s easy to see how this can get twisted as a sinister plot.

“But we do know some things about CWD,” Murphy says. “We know it spreads from deer to deer. We know that it kills deer. We know we’d rather not have it.”

Brad and Tyler Hasheider, who farm outside Sauk City, Wisconsin, dreaded the arrival of CWD, which for the past decade crept steadily closer to their property as the affected area expanded to cover nearly the entire southern half of the state.

“It wasn’t long after [CWD] crossed the Wisconsin River that we started seeing sick deer,” Brad says. “You’ll see a deer that looks listless and is skinny, just sort of bumping around. Then you just don’t see it anymore. I assume it probably died.”

The Hasheiders test every deer they shoot, and they’ve had some test positive for CWD.

“It has affected deer populations, and it’s affected how we hunt,” Tyler says. “But it’s not the end of the world. If we know a deer has CWD, we probably won’t eat it, but the media made it out that all of a sudden all deer meat is poison, and that’s not the case. Deer meat is the best. It’s why we hunt, and we’re going to continue to hunt.”

Slowing the Spread

But for some experts in the field, CWD is the end of the world, or at least the end of the deer hunting and deer management as we know it. Dr. Nancy Hannaway, the federal veterinarian in charge of regulating deer farms, thinks everyone—deer farmers, deer hunters, and wildlife agencies—is being too casual about the spread of CWD and its potential consequences.

“CWD is ultimately a national biosecurity issue,” she says.

Hannaway is stationed at the Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service office in Fort Collins, Colorado, near where CWD was first identified as a clinical disease back in 1967.

“We have bans in place, with wildlife agencies telling hunters not to move carcasses, but we know that it still happens, and some of those could be CWD-positive carcasses,” she says. “And we know that while we have deer farmers enrolled in [the USDA’s] Herd Certification Program who are implementing every best practice, we have some producers who are not.”

Shawn Schafer is one of those deer farmers who acknowledges his industry’s previous lapses.

“You’ll hear a lot of people say that CWD is spread by truck,” says Schafer, who works as the executive director of the North American Deer Farmer’s Association (NADeFA) and owns a deer-breeding operation in North Dakota. “By that, they mean deer farmers moving breeding stock around the country. There has been some evidence of that happening, but I think it’s spread more often by hunters traveling home from a CWD-positive area with a whole carcass.”

Schafer is referring to the prohibition on moving whole deer carcasses out of CWD areas. A growing number of states require any hunter traveling through their jurisdictions to transport only boned-out meat and skulls without brain tissue in an effort to minimize the spread of infectious agents. This fall, Wisconsin’s game commission caused an uproar among the state’s deer hunters when it passed a rule requiring resident hunters to bone out deer carcasses killed in CWD-affected counties. A number of hunters said they’d quit participating in traditional deer camps before following what they called an onerous mandate. The game commission rescinded the new rule.

But CWD “leakage” can happen around game farms too, and Bruce Hoseck’s operation illustrates the problems with a system that enables CWD to hop between farmed and wild deer populations. Why, for instance, did Hoseck’s entire herd test positive for CWD all at once? “I’ve asked myself that a lot,” he says. “The only thing I can figure is that I had a feral cat that got really familiar with my deer. The deer would lick it like it was their fawn, and that cat would use the deer feed troughs like a litterbox. I take in a lot of deer for skull mounts in my taxidermy business, and some of those heads come in from across the river, in Wisconsin. After I boil the heads, I’ll blow out the brains with a pressure washer. Sometimes the cat would eat those brains, and I’d guess if it ate infected brains and then crapped in the feed and my deer ate it, they could get infected too.”

Cost of Containment

When Hoseck opted for “depopulation” of his herd, he also became eligible for federal indemnity payments. Hoseck declined to quote the specific amount he received, but deer farmers whose herds test positive for CWD are eligible for up to $3,000 per animal. Hannaway’s $3 million annual operation budget includes $1 million for these payouts, which come from federal appropriations. In other words, taxpayers’ money.

Meanwhile, Lou Cornicelli, Minnesota DNR’s wildlife research manager, says the state’s game agency has spent $7 million on CWD monitoring and surveillance since 2003, and the vast majority of those funds have come from fishing- and hunting-license revenue.

“Every time a captive facility pops CWD-positive, we figure we’re going to spend a half million dollars to test for the next three years,” Cornicelli says. “Indemnity payments to deer breeders? That’s paid for by you and me—the taxpayers. But CWD surveillance is paid for by the people who buy hunting and fishing licenses. I maintain that it’s cheaper in the long run to pay indemnity to these producers than it is to fight CWD in the wild, but it’s a societal issue, and right now the general public isn’t stepping up to help out.”

A proposed bill in Congress would provide $25 million to state and tribal wildlife agencies to help cover the cost of CWD monitoring in wild-cervid populations. But few supporters give it more than even odds of passing as Congress is gridlocked with larger legislation. Schafer says his deer farmer’s association would support the bill and more funding for CWD research.

Read Next: Four Things Hunters Should Know About CWD

Pulling Together

Working on the frontier of CWD expansion, Todd Froberg says that he has only to look east to Wisconsin to see what’s at risk in Minnesota. “People say that wildlife managers tried and failed to contain the disease in Wisconsin, so why should we care about helping contain the disease here?” Froberg says. “But in Minnesota’s case, we think we caught CWD early. Our prevalence is very low, and we have the chance very early on in the outbreak to contain it to a local area without it becoming endemic” over a wider landscape.

But in order to contain CWD, landowners need to allow hunters access to harvest deer, hunters need to test their deer and then not transport parts of carcasses that might harbor CWD, and game farms need to tighten up their operations—and face tougher penalties for lapses.

“The risk of doing nothing, or not enough, is that there will come a time when people will look back and ask why we didn’t do more when we had the chance,” Cornicelli says. “I don’t see a way to put CWD back in the bottle, but I do think we need to work hard right now to keep it as limited and as rare as possible.”

Across the river in Wisconsin, Brad Hasheider says he’ll continue to monitor and test for CWD, but he’s not about to quit hunting. “I like my local DNR guys, and I trust what they’re doing,” he says. “If I can be a part of a solution, I’m all ears. Just tell me how.”