I’m tired of griping about spot burning. At this point, I just kind of hate the term. It’s not that I think it’s not a problem, or isn’t real, or isn’t capable of altering fisheries, because it’s all those things. I’ve been accused of it many times in my career in fishing media. I’ve also been the victim of it many times throughout my life. But I get sick of rapping about it because it’s an inevitability. Social media and tech are here to stay. There’s no going back.

The question anglers should be asking is: How do we forge ahead in the information age without compromising fisheries? To answer it, you must first identify the biggest culprits—in other words, which platforms burn fishing spots the hardest. Facebook and Instagram? Sure, grip-and-grins of trophy fish that show obvious landmarks in the background don’t help. Forums? In my experience, you give away too many goods and your post will get shut down. I’d posit that fishing apps produce more burn victims than any other platform. The good news is that some developers are coming up with ways to incorporate ethics into their apps, but to understand the significance of that, we must first look at Fishbrain—the app anglers love to hate and hate to love.

Brain Games

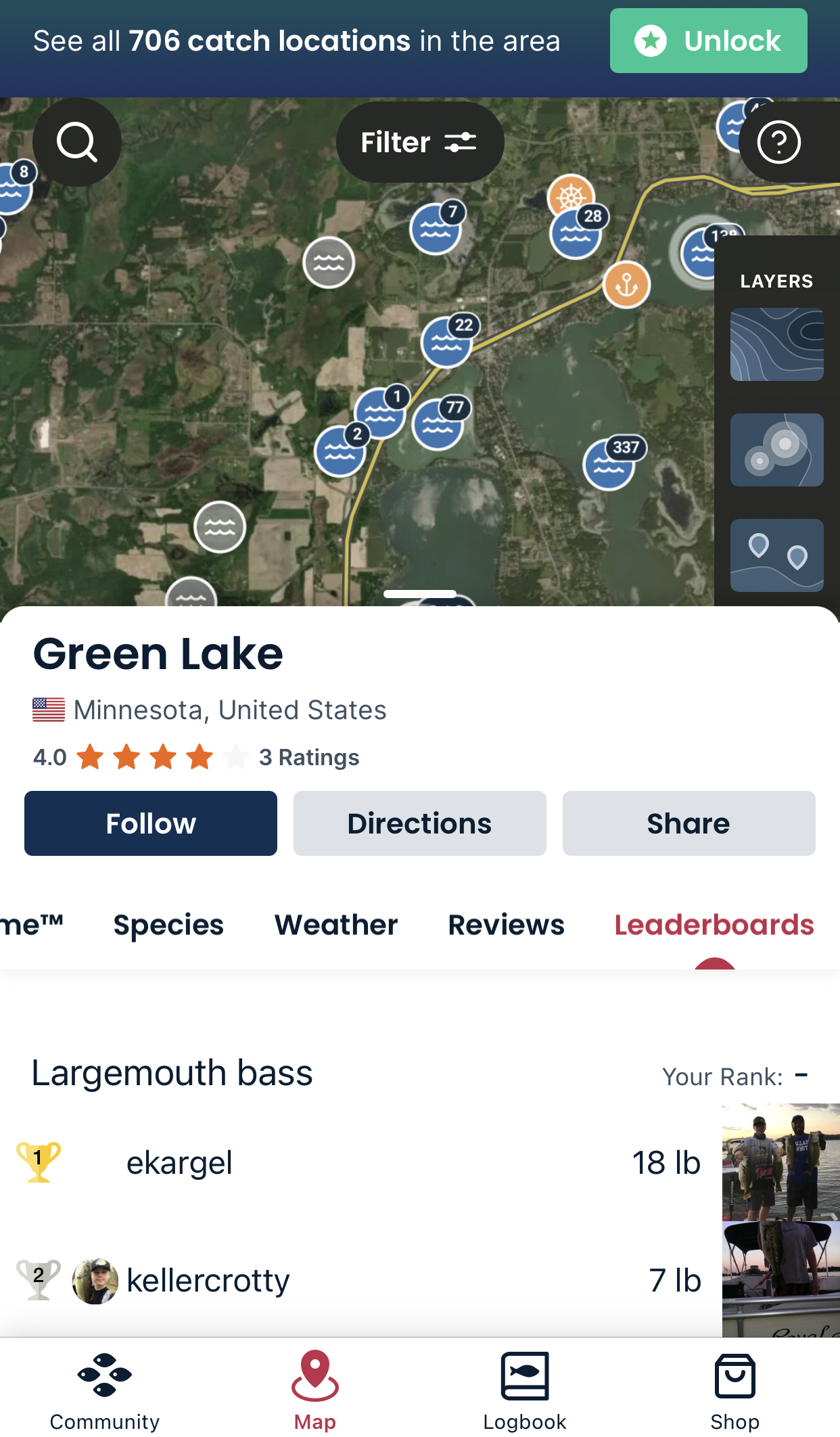

Fishbrain says it has 14 million users worldwide who share their catches, create pins, and give fishing reports on waters across the globe week after week. Fishbrain’s reach is incredibly vast. For example, there are almost 30 pins and reports on one tiny, insignificant bass pond in central New Jersey where I grew up fishing (more on this in a moment.) I gleaned those numbers from my 26-year-old buddy Pete Scharf, because I don’t have Fishbrain.

He believes there are two primary types of people who are attracted to the app—those who want to boost their ego by posting catches and those who benefit from the ego junkies by fishing their spots. Scharf falls into the latter camp.

“I’ve had Fishbrain for about four years now,” he tells me. “I’ve never once posted anything. But for $7.99 a month it’s hard to beat. If I want to catch, say, big pickerel, I can set filters so I only see locations where users have posted pickerel bigger than 20 inches. I mean, how do you not utilize a data resource like that? But at the same time, I’d prefer nobody posted anything on the app ever. I guess the way I look at it is since I have no control over what other people post, I may as well use their information to my advantage.”

Fishbrain is promoted as a learning and journaling tool, which isn’t inaccurate. The app aggregates and logs weather and water condition data for your catch, helps you find public access and bait shops, and it will even recommend lures based on what other users in the area have been reporting success with. (You can buy most of these lures right through the app as well.) These are all fine features, but Scharf doesn’t use a single one of them. He uses Fishbrain solely to look at maps and see where other users have posted catches.

“Those spots get posted for the same reasons fish pictures with distinct backgrounds get posted on Facebook and Instagram,” Scharf says. “People want to show off, and they don’t care if they’re revealing their location when they show off.”

The Story of a Burned Spot

Let me take you back to that little bass pond in central New Jersey. By the book, it was perfect. It’s only a couple acres, making it ideal for foot missions. The shallow end is ringed with crisp green lilies. Dragonflies dance over them, and the sharp sucks of bluegills taking swings at these airborne morsels carry across the water. There’s a dike at the other end and a spillway that was installed long before my time, back when this property was still a private farm. There, at the deeper end, milfoil grows thick along the bank, sloping away to create a juicy edge.

When I was a little squirt, reaching this pond meant parking on the winding country road at a shallow pull-off and traversing the old farm property all the way to the back. I’d be dripping with DEET, trudging through waist-high grass, my sneakers caked in mud. There was rarely anyone fishing, and you could rely on catching at least one bass worthy of a photo. Through high school, this was the local spot most likely to kick out a 4-plus-pounder. Nowadays, if I manage a single 1-pound bass here, it’s a win.

This pond used to feel like a little secret, but now it’s being served up on a silver platter.

Part of the problem is that this county-owned property has recently been transformed from an overgrown public land to a safe and secure nature experience for anyone with a fishing rod, recumbent bicycle, or new pair of Skechers Massage Fit shoes. There are new signs, new paved parking lots, maps, and freshly compacted gravel trails everywhere. Then you have the Fishbrain factor. The first user report from this pond was published in July 2017. The caption for the accompanying photo, taken in the corner with the lily pads, reads: “Not big, but my first bass from this pond. I knew there were bass in here.”

I can’t help but imagine the person who posted that report felt like a bit of a pioneer. In the Fishbrain world, which functions similarly to any social media platform, he was first, and first is a big deal. But it’s hard not to psychoanalyze that decision. If you explored a new pond, had success, perceived it as hidden or under-fished, and had the forethought to realize this small body of water can only take so much pressure, would you share everything about it—including the spot you stood while catching fish—on a platform that boasts 14 million other anglers?

Feeling the Burn

Spot burning wasn’t invented in the social media era, nor was getting a big head about your fishing prowess. When I was 20 years old—just before the social media boom—I wrote a story for a local magazine detailing the ins and outs of fishing a jetty I frequented for stripers. At the time, I was so proud of everything I learned at that jetty—I felt so dialed. Putting it on paper was a way to solidify that I was the authority on the spot. I was so blinded by wanting to look like the man that I never considered that the story might piss off other people who fish the same rock pile, many of whom probably had it far more dialed than me. The hate mail to the publication was legendary. I was deeply crushed, but I learned a huge lesson: You can share the how, what, and why, but when dealing with the where, be cautious. From then on, I always consider the audience, size of the water, and size of the accessible area. Unfortunately, it’s getting harder and harder to share what I learned from that mistake with the new generation of anglers that craves fast information and wants the shortcut to success.

I know that Fishbrain and the very similar Fishidy bring a lot of benefits. One could easily make the argument that more and faster catching is the surest path to new angler retention. It’s no secret that fishing has seen an incredible participation boom since the Covid pandemic, which helped app sales soar. Still, whenever I see a kid riding his or her bike down the street with a fishing rod, I get the warm fuzzies because it’s so rare these days. Even when I’m at that bass pond that drives me insane now, I can see myself in the kids throwing Googan Squad lures. If Fishbrain helped flip that kid’s switch, that’s a good thing, because I recognize that not everyone grows up in a family like mine where dad, granddad, and even my mom would take me fishing or drop me off at the lake as often as I wanted to go.

Like many other writers, I’ve made a career out of getting people excited about fishing and passing on what I have learned to help them catch more fish.

But I also tend to believe that true fishing success is a product of fishing failure. You learn the right thing to cast because you were casting the wrong thing. You find a killer spot because you sifted through a bunch of shitty spots first. You choose a body of water based on gut instinct that was sharpened by a drive to know your local spots intimately. You heard a rumor at the tackle shop and decided to explore it for yourself. You started making the right calls because you were becoming a sharper angler—not because an algorithm narrowed it down for you. In my opinion, you learn more by not catching fish than catching them, which begs the question: While apps like Fishbrain may get more new anglers catching faster, are they becoming well-rounded anglers in the process? To scoot down that rabbit hole a bit further, does it really matter?

I also know that technology and the race for information will never stop infiltrating angling, but I can’t help but wonder: Is there a better way?

A Smarter Route

The guys at Trout Routes think they’ve found a way to provide fast information that gets you in the right classroom without spoon feeding you the lessons that should be learned via the school of hard knocks.

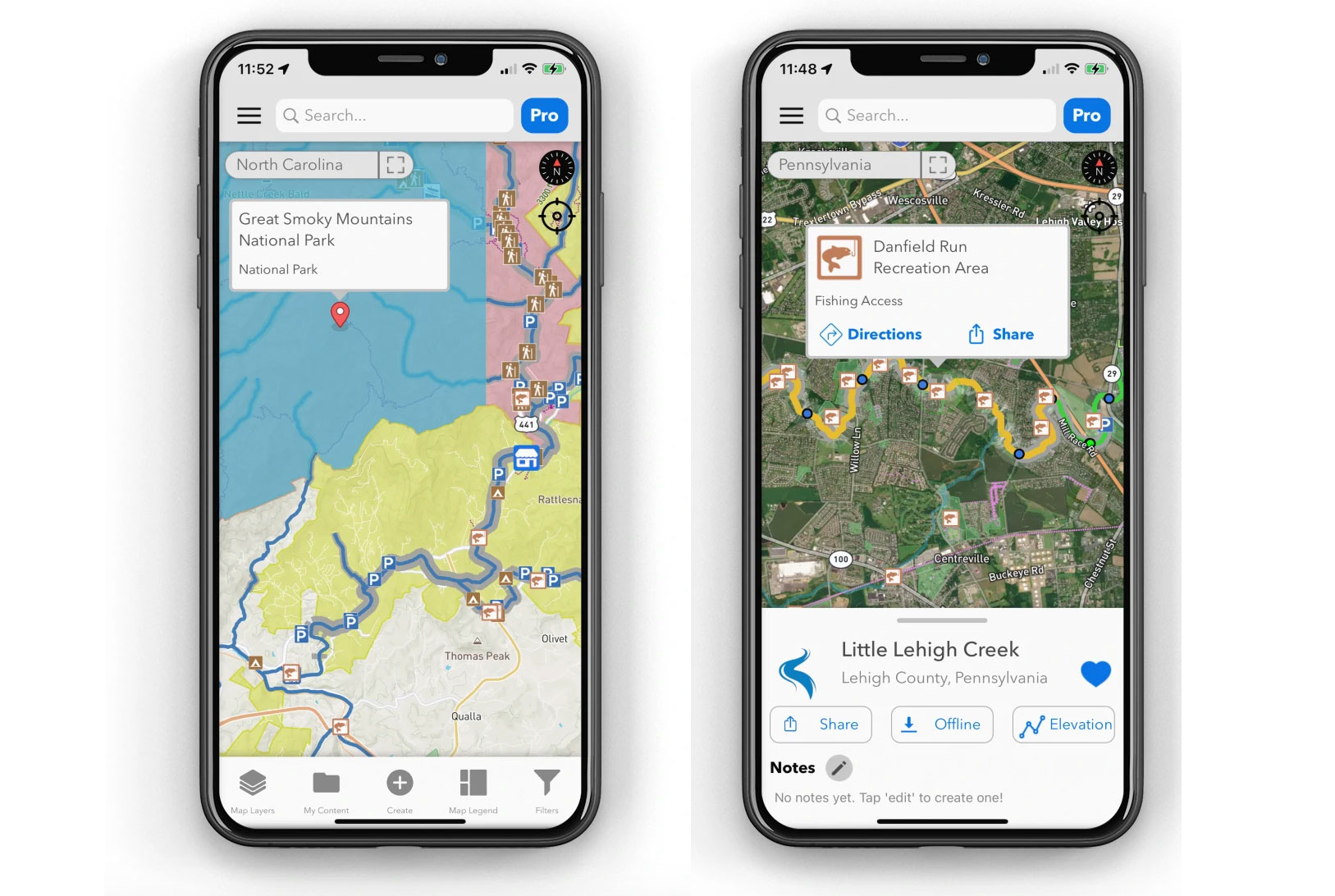

Trout Routes launched in March 2019. It’s the brainchild of Zach Pope. Since May of 2020, subscriptions to the app, which specifically maps out moving trout water in each state, has tripled year over year. Pope is so smitten with the research that goes into the mapping, he even includes water that has the potential to hold fish at some point during the season based on average temperatures and how it connects to larger systems known to hold trout. So how is making this information easily available any less harmful than Fishbrain’s model? Trout Routes isn’t using crowd-sourced data.

“The key difference between us and everyone else is that we are very unidirectional. We do all our own research to develop our maps and use zero information from our users,” says Pope. “We do not allow our users to share information between each other, you can’t post stream notes or reviews or anything like that. We are just a map provider versus a community.”

Trout Routes is providing information that already exists in a way that’s easy to access. States like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, as examples, have detailed trout water maps on their state agency websites. Trout Routes is just making that information easier to find and less clunky to digest. Pope and his team are aggregating public information, and then fleshing out the rest with hard research. Pope is talking to sources, reading books, and doing whatever he can to create the most comprehensive trout maps ever. To date, 24 states have been fully mapped. Pope says nine more will be added soon. Every access point, every piece of data the app provides, Pope figured out without the input of users on the ground. Still, it doesn’t mean the app hasn’t gotten pushback.

“We get the most criticism from guides in the West,” Pope says. “I think they view us as a threat unnecessarily. I think they fear that with this much information in the palm of your hand, people will no longer need to come into the shop and buy flies. I think guides also fear that we’re showing people the waters they like to fish on their days off. But in my opinion, the primary role of a guide is not to tell you where to fish, it’s to tell you how to fish. Trout Routes is never going to teach you how to fish. We’re just telling you where to begin your day. We’re not going to tell you where the holes are.”

One of Pope’s hopes for Trout Routes is that it will take pressure off some bodies of water. To use the Madison River as an example, he believes part of the reason it’s so overly crowded is simply that there’s no shortage of information about in on the internet. People have heard of it, it’s famous, so that’s where they go. He believes that by presenting other options, it could spread out the crowds. But he does recognize the doubled-edged sword Trout Routes creates, especially considering smaller wild trout streams are delicate.

“Someone was eventually going to do what we’re doing whether you like it or not,” Pope says. “Fishbrain might have eventually started mapping trout streams. So, I would much rather we do it because we do care about conservation, and we do care about the fishing industry. We let ethics dictate what we do and do not include in the app. My vision is that we actually drive traffic into fly shops. It’s one of the reasons I create custom icons within the app for as many fly shops as I can.”

It would be a stretch to suggest that the Trout Routes has solved the problem. Inevitably, it’s going to put some people on a tucked-away mountain stream that felt like the personal playground of just a handful of anglers in the know. What it won’t do, however, is single that stream out as the best place to fish because more 14-inch wild brookies have been caught there than in other area streams.

The ironic part of analyzing the pros and cons of fishing apps is that most of the advantages they offer have been readily available since Google Earth launched in 2005. Anyone could have found my bass pond using the program. Anyone can explore mountain streams with it as well. Trout Routes, in my opinion, is more akin to Google Earth because it still forces you to explore and learn whether the stream is worth your time or not. Ultimately, what I see getting kicked to the curb in modern angling is the willingness to explore, experiment, and fail (a lot.) For me, that learning process is the fun part. I don’t believe the real problem is that the technology is getting better. The problem is that we’re getting lazier, and assuming this trend continues, we’re going to keep feeling the burn.