When I was growing up, the freezer in the Frigidaire in our kitchen was my personal taxidermist. If I caught a fish I was proud of, there it would live sometimes for months, or at least until my grandpa, uncles, and neighbors had all gotten their chance to gawk at my trophy. I was probably seven when I first started begging my dad to mount every trophy fish I caught. Given the price of fish taxidermy, the answer was “no” every time.

Then, in 2002, I caught my first trout over 20 inches on a fly that I had tied myself. This had to be the one. “Dad, this can be my birthday and Christmas present, combined,” I said with puppy dog eyes. He finally bit and I was ecstatic.

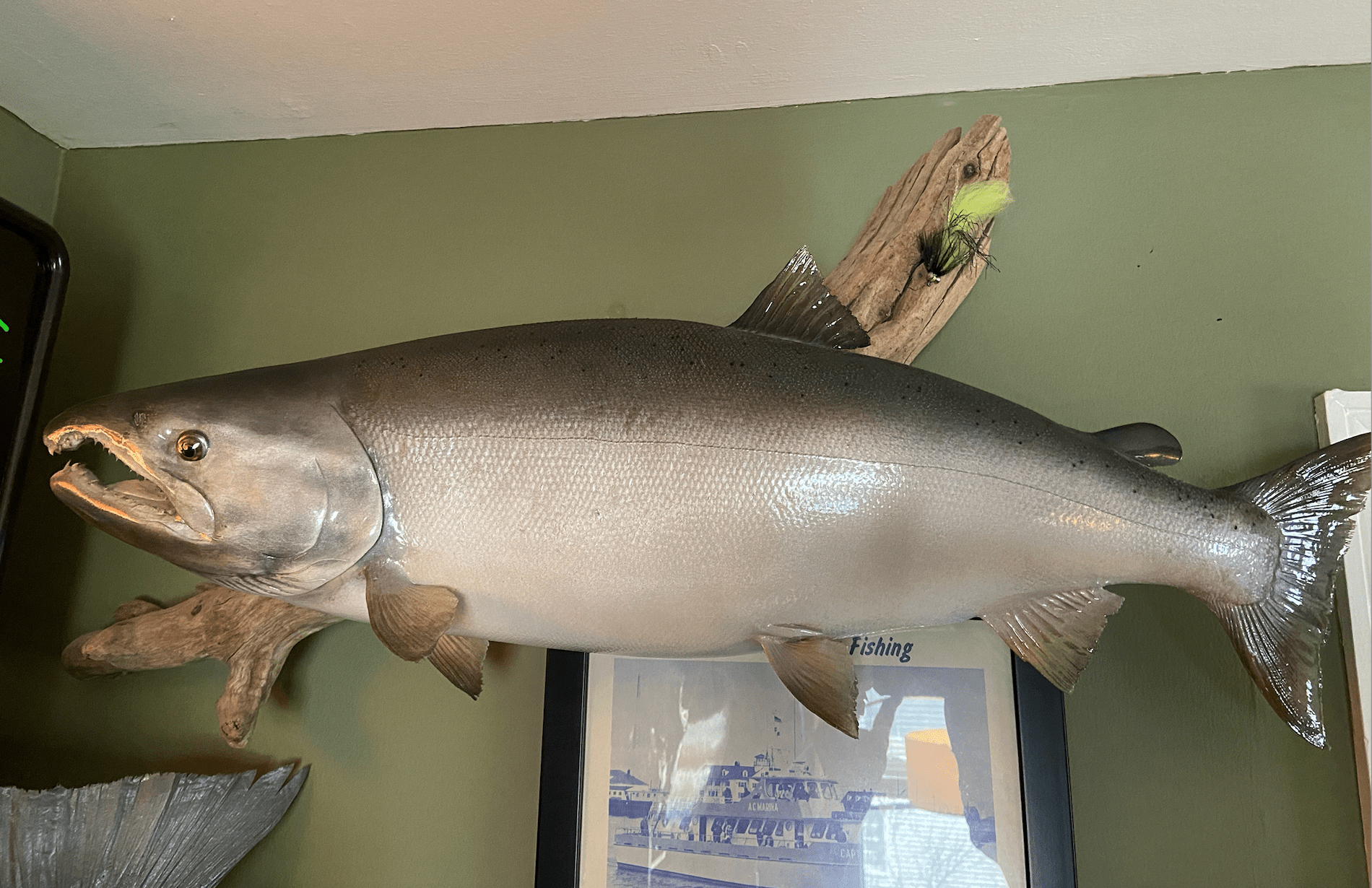

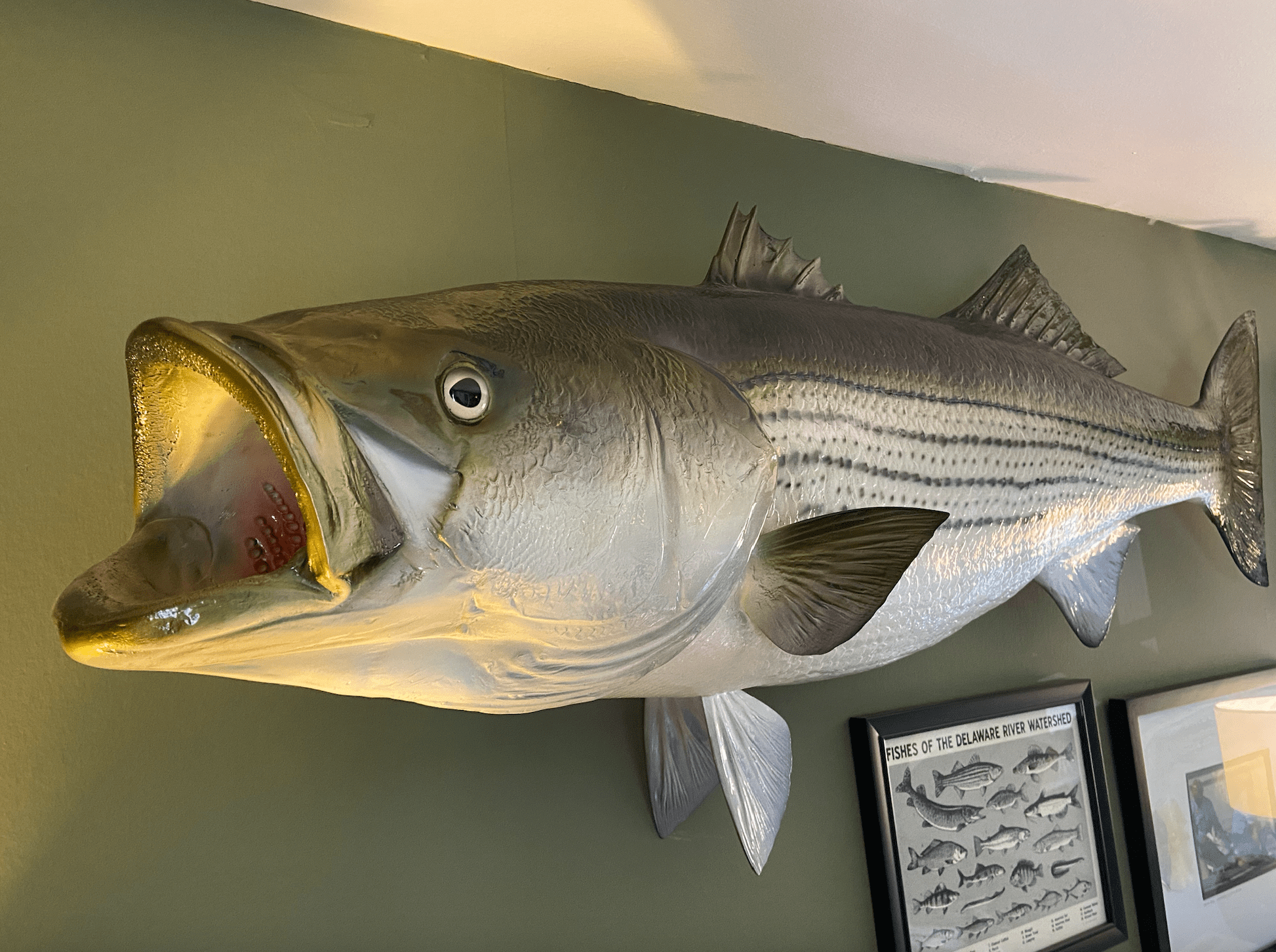

That brown trout still hangs in my office, along with a 200-pound tarpon, 47-pound striper, 13-pound walleye, and a bunch of other fish that I’ve deemed worthy of the wall over the last 20 years. In that time, I’ve explored all different methods for preserving a memorable catch beyond simply taking a photo. There’s one for every budget and taste, so I’m breaking them down here because it’s my belief that every angler should have at least one fish on the wall. Putting it there and stepping back to look for the first time is almost as big a rush as when you got put it in the net.

Skin Mounting

For decades, skin mounting was the most popular method of preserving a catch. The funny thing is, it’s not as if some of the other methods mentioned later didn’t also exist 50-plus years ago, it’s just that I believe in the years before catch and release became more of the norm and we didn’t face as many fishing related conservation issues as we do today, skin mounting was just sort of accepted as “the way it’s done.” Many people (myself included in some cases), feel the need to have the actual fish we caught on the wall, as opposed to a replica or representation.

Traditional skin mounting achieves this by chemically preserving and drying the skin, fins, and head, which are then reconfigured around a foam body and repainted to bring the catch back to life, if you will. Though techniques have changed, there are still many expectational taxidermists who work with skin. Most critical, however, is the need to study your taxidermist’s portfolio. Skin is incredibly challenging to work with, and if you visit enough dive bars in fishy places, you’ll find loads of examples of poor skin mounts. What I’m saying is, if you’re on a budget, opt out of skin. If you’re not willing to pay top dollar for quality work, there’s a greater risk that you won’t be happy with the finished product.

Pros: I know several anglers who have opted for skin mounts simply because they felt their catch was so special or unique or had characteristics that wouldn’t be captured via a fiberglass replica that they sacrificed the fish for the taxidermy. Mind you, these decisions were reserved for milestone stripers and largemouths that, in several cases, anglers spent years chasing. Similarly, I once scored a silver salmon in Alaska that was a bit of a miracle catch. I really wanted it mounted and didn’t feel like a replica made thousands of miles from where I caught it would do it justice. I took it to a taxidermist not far from where I landed it who specialized in skin mounts, and while I paid a lot more money, it was worth it. Regardless of the ethics, you also end up with a one-of-a-kind mount, and it’s hard to deny that there’s something satisfying about that.

Cons: The biggest downside to skin mounting is that you have no choice but to sacrifice the catch simply to create wall décor. And you can’t have your cake…or fish…and eat it, too. There are, however, other things to consider, namely the shelf life of a skin mount. These days, taxidermists tend to use little more than the skin from the actual catch. Sometimes the fins remain intact, but quite often plastic fins are swapped in. Likewise, I don’t know any modern taxidermists who use the fish’s real head. A molded plastic, foam, or resin head is fitted to the body. This is because fish heads retain loads of oils. Have you ever seen an old skin mount that was peeling and melting? It happens because over time, those oils can seep through the skin and mar the finish. Modern techniques have certainly extended skin mount longevity, but you still can’t bank on your mount looking as perfect as the day you picked it up 10 or 20 years from now. Finally, it’s also worth considering that once you decide to skin mount a fish, you must care for it and preserve it in the interim until it gets in the hands of the taxidermists. You can’t drag it around or let it get beat up in the cooler. You need to transport it gently so scales aren’t getting knocked off, wrap it in towels or newspaper before freezing it whole, and then be ready to pay handsomely to ship the frozen fish if your taxidermist isn’t local.

Fiberglass Replica

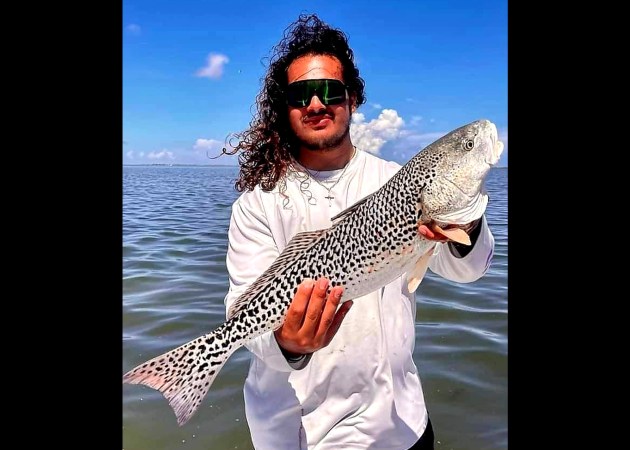

The boom in the fiberglass fish replica industry is a direct result of the collective change in angling conservation ethics. Specifically, companies like Gray Taxidermy (which started out as a skin mount operation) and King Sailfish Mounts have led the charge, donating thousands of dollars along the way to support conservation projects and fund fish-related research. It’s not a completely death-free method, of course, because to offer such a wide variety of species in different sizes, a real fish had to be sacrificed at some point to create the molds that allow replica artists to produce copies for years to come. Still, the sacrifice of a few fish has allowed us to release so many more fish, allowing you to put your trophy on the wall and let it swim off to fight another day. All you have to do is take length and girth measurements of the catch and get some clean photos of all sides (especially any unique characteristics or markings). Send the photos and measurements off to a replica maker and wait for FedEx to drop your trophy on the porch.

Just keep in mind that not all replica makers are equal in quality. Like anything that involves artistic talent, you usually get what you’re willing to pay for. The aforementioned makers do a great job of talking you through the process, ensuring that the finish and markings match your catch as closely as possible. They also employ expert painters. Likewise, you can find plenty of independent replica makers who do fantastic work. Conversely, you’ll also find extremely budget-friendly replica operations, but be warned: The cheaper you go, the less personal the touches will be. You might be getting a muskie back, but will it really look like your muskie?

Pros: Aside from the fact that your fish doesn’t have to die to spice up the living room wall, fiberglass replica mounts last forever. They’re extremely light and can be wiped down and dusted time and time again without worrying about damaging fins or scales. They’ll never rot or seep oil, and even if yours gets damaged, fiberglass fish are very easy to repair compared to skin mount restorations, which can be arduous and costly.

Cons: Assuming you picked a replica maker who pays extreme attention to detail, your mount will be unique, but only in regards to the paint job. Visit any replica fish website and you’ll find a finite number of molds. As an example, I wanted a replica of my first 40-plus-pound striped bass, which measured 50.5 inches. At the time, the length options offered were 48 inches, 50 inches, and 52 inches. I opted for 50, and while it’s easy to say, “what’s the big deal, it’s a half-inch?” the bottom line is that the fish on my wall is very close to the one I caught, but not exact. Likewise, you might not find options beyond “fish facing left” or “fish facing right.” No matter how you slice it, hundreds if not thousands of those fish have already been molded, painted, and reside in man caves all over the country. Does that detract from the conservation benefits of fiberglass? Hell no, but if you’re a stickler for originality, fiberglass replicas might not be for you.

Wood Carving

I have many fiberglass replica mounts. I also have a few skin mounts. I’m also the proud owner of a couple fish carvings, and as soon as I got my first one, I realized this was, in my opinion, the best way to preserve your catch. The caveat, however, is that it’s also the most expensive way to put a fish on the wall. But hear me out.

I have a snakehead and tiger trout carved by Rich Metzger, an award-winning artist who in my area of the East Coast. Preston Hagget of Adirondack Fish Sculptures is another well known carver. Both guys have the ability to create fish that are exceptionally lifelike, and it’s my belief that you have to find a carver with that level of skill and be willing to pay the high rates if you’re considering a carving. The fact is, lots of people carve wooden fish, but if you’re treating it as fish taxidermy, you don’t want something that looks like it belongs in a gift shop.

There’s a not-so-fine line between folk art and a taxidermy alternative when it comes to wood. I know several folks who have gone with budget carvers on Etsy and the like. What they get back might look like a pike or trout or walleye, but as a genuine representation of the real fish they put in the net, the carvings fall short. All taxidermy is art, but in the case of a wood carving, you are truly commissioning fine art, which means you’re the ultimate boss. Just be sure to provide a carver with detailed photos, videos, and length and girth measurements of your catch.

Pros: Assuming you’re working with a skilled carver, the best part about this method is that the sky’s the limit because nothing hinges on a dead fish or a mold. You’re starting from scratch, so if you wanted, say, your smallmouth angling down, gills flared, fins splayed, about to inhale a crayfish off the bottom, a good carver can make your vision a reality. Want a specific body curvature in your steelhead instead of a plain old side profile? A carver can do it. When Metzger carved my snakehead, he perfectly captured the undulating ripple of the dorsal fin, which happens when these fish charge a topwater frog. He carved a mouse that’s peering over a rock above the tiger trout because I caught it on a mouse pattern. Not only is a good carving one-of-a-kind, but it can be elevated from something you hang in the finished basement to something worthy of prime real estate upstairs, especially if it’s so good it makes house guests say, “No way is that wood!”

Cons: Other than price, there aren’t many downsides here. I have noticed that turnaround times tend to be longer than with other fish mount methods, especially if you’re dealing with a high-demand carver. Of course, if you’re willing to go all in on wood, it’ll be worth the wait.

Gyotaku

Gyotaku is the ancient Japanese art of printing a fish on rice paper. A whole fish is covered in ink and the paper is pressed on top of it, leaving a detailed, to-scale image of the catch. It may sound simple, but it’s more complex than you think.

The cool thing about gyotaku is that you can do it at home. Though I’ve never tried printing a fish I caught, I’ve done it several times with bluegills and pickerel my young kids brought home, and it’s a project they love. The reality, however, is that making a DIY gyotaku print worthy of a frame and wall space takes practice and skill. Using it to simply commemorate a catch or give the kiddos something to hang on the fridge does not. There are professional gyotaku artists all over the country who create gorgeous prints any angler would be proud to hang. Some keep things traditional, using a single color to print, while others embellish prints with watercolor details to make the fish look even more realistic. Whether you’re trying it for fun or looking for the perfect artist to print your PB perch, there are plenty of gyotaku options.

READ NEXT: The Biggest Mistakes Parents Make When Trying to Raise a Diehard Angler

Pros: If you’re using a water based, non-toxic ink or paint, your fish can still be consumed after your at-home gyotaku session. In fact, ancient Japanese fishermen preferred the method because fish could still be taken to market after printing. Because the fish can still wind up on the table, I see gyotaku as a less wasteful version of skin mounting, as you still end up with something created directly from the fish you caught. The process also allows you or an artist to get creative. I’ve seen gyotaku prints done on nautical charts of the area where fish were caught, as well as fishing scenes tastefully worked into the print to make it that much more unique.

Cons: Keep in mind that the bigger the fish you’re trying to print, the more wall space you’re going to need to hang it up. It might sound like a no brainer, but I’ve seen gyotakus of bluefin tuna and giant striped bass, and the paper needed to capture the whole fish was so big that by the time they were framed, they required much more wall real estate than those same fish would have in replica or skin mount form.

Fish Prints

Several years ago, a company called Fish Print Shop hit the scene with a novel idea for those who wanted to preserve their catch on a budget, without killing the fish. They worked with well-known artists to build a database of fish images that could be digitally scaled up or down to match the size of your trophy. Once properly sized, the fish would be printed in full color on fancy stock, with all the catch data and location beautifully handwritten in the corner. I can attest to the quality of the art as I know several of the artists were famous for their work in detailed species identification books. On paper—pardon the pun—the idea seemed simple and elegant, but the system has one flaw worth noting.

Pros: Not only can you release your fish, but you don’t even need to take detailed photos to commission a print. In this case, think of the product less as taxidermy and more as a wall-worthy page from an elegant fishing journal commemorating the entire event instead of just the fish.

Cons: The one setback I noticed is that the company’s database of imagery lacked a range of fish sizes, which meant the scaling up or down of any one of those images could lead to a poor representation of your catch depending on the species. To use mahi mahi as an example, a 30-inch male—or bull—mahi is not going to have the same look and body structure as an 80-pound bull. So, if the bull on file looks like an 80-pounder, your print of the 30-incher you caught is just going to look like a small image of a giant mahi. So ask to see the fish on file that will be used to represent your catch, as the scaling issue will vary based on species and available images.