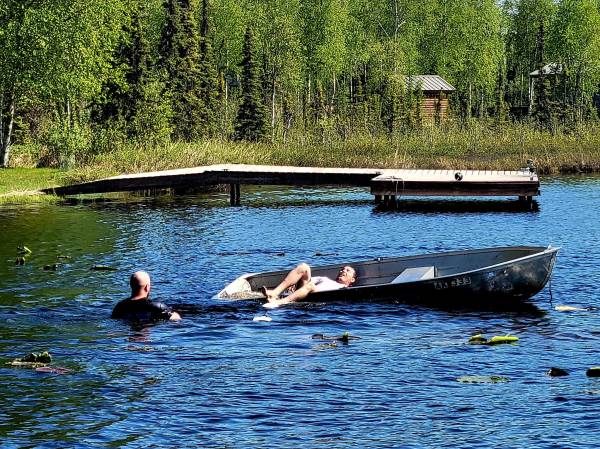

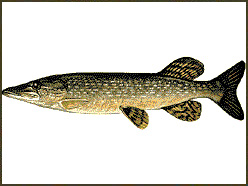

On October 21, the news website Ktoo.org out of Alaska published a story titled, “Programmed to Eat: Northern Pike Mauls Husky at North Pole Gravel Pit.” It was a must-click for me. The article recounts the saga of long-time North Pole resident Shannon Dhondt, who took her dogs for a swim at an area gravel pit in September. Luckily, her chihuahua, Mulan, wanted nothing to do with the water, but her husky-greyhound mix, Murphy, took a dip at the pit’s edge. That’s when all hell broke loose. From the story:

“Out of nowhere, bam, here’s this big old huge fish, which, I didn’t know what it was,” Dhondt said. “Three feet, hanging off his muzzle, you know, and he starts shaking his head and this thing is holding on.”

According to the article, Murphy managed to get the northern pike off his face with his paws, but then it swung around and grabbed the dog’s leg. Now, if you think I’m leading up to poking fun at this event, I’m not. Murphy was fine, but the pike was aggressive enough that it caused some legitimate damage. There’s a photo in the piece of the poor pup immediately after the attack lying on a bed that’s soaked in blood, teeth marks dotting his muzzle and foot.

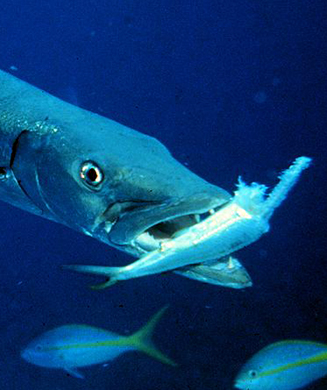

Pike and muskie attacks, though rare, do happen. They happen more often than with any other “scary” freshwater fish, yet both species have somehow managed to evade becoming the main characters in stupid B horror movies. The same cannot be said of other fish that have struck 100% unfounded terror in the hearts of uninformed masses.

Gator Gar

Alligator gar are living dinosaurs. They’ve been swimming in our country for millions of years, and historically ranged as far north as Ohio. Though these armor-plated giants once flourished throughout the Mississippi River drainage, these days they are found in numbers only in East Texas and across the Gulf Coast to North Florida. They’re certainly not a coveted food fish, so we didn’t wipe them out to supply the market. We killed them, at least partially, out of fear.

As the American population grew and more folks ended up living along gar-filled waterways, people naturally became uneasy about the 100-plus-pound fish with a face full of gnarly teeth swimming where their livestock drank and kids swam. Gator gar are imposing, no doubt, but those teeth are designed to hold small fish. Plus, gar don’t really hunt. They lay on the bottom and wait for a carp or sucker to swim by. To date, hundreds of years later, there has never been a 100% confirmed case of a gar biting a human, with culprits in such cases most likely being the work of an actual alligator, not the fish the shares its name. Still, that didn’t stop eradication efforts.

In the 1930s, Texas Game & Fish unveiled the Electric Gar Destroyer, a boat capable of cruising along and pumping huge voltage into the water. The program was cloaked as a solution to saving more coveted fish from being wiped out by gar, even though decades later it would be proven that alligator gar play an important role role in keeping non-native carp and other less desirable species in check. Still, in those days, no one was sad about fewer big, ugly gar swimming around. Even now, they are a popular bowfishing target. I’m all for bowfishing, but not when you’re killing, just for kicks, a fish that could have taken 80 years or more to reach 100 pounds.

Snake Bitten

Back in the early 2000s when invasive snakeheads were first covered by the national news, all it took was one biologist saying that they can walk on land and all bets were off. People in Maryland were keeping their Pomeranians on a tight leash and locking the cat inside. Snakeheads sparked so much fear and anxiety that within a couple years of their arrival, we were treated to such blockbusters as “Snakehead Terror,” “Snakehead Swamp,” and my personal favorite, “Frankenfish.” Twenty plus years have passed since these fish showed up, and there’s no trail of dead squirrels and bunnies. They sure as hell have never bitten a human unprovoked.

“Walk on land” was a dumbed-down, irresponsible way of saying, “they can move between bodies of water if the conditions are perfect.” Snakeheads can breathe air, and as a survival mechanism, they can shift between waterways assuming they’re close together and there’s wet grass or mud between them. They would only do this if, for whatever reason, the water they were in was becoming unlivable. But a snakehead isn’t wiggling down the interstate, and even if it was it’s not biting off one of your toes along the way. Meanwhile pike and muskies are drawing human blood.

READ NEXT: Maryland Will Pay You to Catch, Kill, and Report Tagged Northern Snakeheads

Sink Your Teeth In

Perhaps the most well-known muskie attack happened to Kim Driver. In July 2020 while wading in the Winnipeg River, a muskie latched onto Driver’s calf, began headshaking violently, and allegedly pulled her underwater. She was left with deep lacerations and punctures that would later require plastic surgery. Barely a year later, Matt Gervais was taking a 3-mile swim in Ontario’s Lake St. Clair when a muskie clamped down on his hand. In 2017, a little girl on a paddle board was attacked by a muskie in Minnesota.

Human attacks aside, there are plenty of tales floating around about “purse dogs” getting taken out by pike and muskies, and I’m sure Mulan the chihuahua sat by her brother Murphy’s side that night after the Alaska attack breathing a puppy sigh of relief. If you understand fish, however, the attack makes some sense. Alaska has a short summer. By September, fish know the winter season is coming. This is why fishing for pike and muskies is so good in the fall. They’re a little hungrier, so if you want something to give you that horror movie dread, it’s not gar and snakeheads. It’s dipping your little piggies in pike and muskie water after Labor Day.