Capt. Billy Rotne is quietly freaking out. He’s stabbed his finger on the sharp dorsal fin of a redfish that bucked just as he released it. Now he’s bleeding. It’s not much, maybe a drip every five seconds, but as Rotne rummages through the forward hold of his flats boat for his first-aid kit, his urgency elevates this from a garden-variety fishing prick into something more critical.

He finds his medical kit, but the Neosporin, in a squeeze packet that looks like takeout mustard, expired last year.

“Better than nothing,” Rotne says as he slathers his finger with the medicinal ointment. “I know this seems silly, but I don’t mess around with the chance of infection. Who knows what’s in this water.”

If anybody should know, it’s Rotne. For the past 14 years, he’s worked as a registered fishing captain, guiding anglers around northern Florida’s premier inshore destinations. His favorite place—and method—is poling redfish anglers around Mosquito Lagoon, putting them on the biggest bull reds of their lives.

I’m a beneficiary of his expertise. He anchors beside a spreading shoreline palmetto and tells me to punch my blue crab into the south wind. A short soak later, the line twitches, as if Rotne had scripted it. The rod loads, and after a bicep-numbing fight, a holy-hell 40-pound redfish poses in my arms for a quick photo.

Stoked as we are with that trophy fish, I get the idea that Rotne would have been even happier with a juvenile red, which would promise productive trips in the future. The reality is that over the past couple of years, Rotne has struggled to put fish in the boat. His go-to spots have changed. Fish have relocated. Even the appearance of the water is different.

“We should be seeing a dark bottom of sea grass,” Rotne says as he poles me around Mosquito Lagoon, the skeletal towers of Kennedy Space Center hulking a few miles to our south. “But it’s almost uniformly white. The sea grass is disappearing, which sucks for gamefish like seatrout, because when they’re juveniles, they use the grass to hide from pinfish and other predators. But it also sucks for water quality. If you don’t have sea grass holding the bottom, then every time the wind blows, sediment gets stirred up. The more sediment, the darker the water. The darker the water, the more heat it absorbs. The warmer the water, the more chemically reactive it becomes.” The catalyst for chemical reactions here—and the reason Rotne is so worried about his bleeding finger—is hundreds of thousands of gallons of fecal matter that have washed into the lagoon from leaking septic tanks across rural Brevard County.

“It’s not just human waste I worry about,” Rotne says as we resume poling for tailing redfish, his finger finally bandaged. “The amount of pharmaceuticals—we’re talking geriatric Florida here, after all—along with human pathogens that get washed into this bay has created super-resistant bacteria. I won’t wade this water, and I sure as hell won’t eat a fish from here.”

Defined By Water

Rotne’s categorical indictment of the aquatic environment is jarring, but it confirms rumors that have been circulating around this destination-angling community for a while—Florida’s marine fisheries are showing uncharacteristic fragility. It started with increasingly dire reports from Florida Bay, the shallow-water mecca for inshore species between the tip of Florida’s peninsula and the Keys. Then Atlantic Coast communities were hit with a toxic algal bloom that drove visitors out of the water and residents out of their expensive beach homes. Locals still call it the Lost Summer of 2013. In 2016, and again in 2017, red tide killed millions of fish up and down the Gulf Coast, creating a stench that undid years of Sunshine State tourism promotions.

But last year was the clincher.

“We call it Toxic ’18 because of the convergence of pollution-driven tragedies on a scale we’ve never witnessed here,” says Terry Gibson, a former fishing guide who shuttered his charter business because he couldn’t consistently put clients on fish (disclosure: Gibson is also a former fishing editor of Outdoor Life). He now works as a water-policy expert for a number of advocacy groups. “We had a virtual crayon-box of algal blooms. Red tide in Sarasota Bay. Blue-green algae in Indian River Lagoon. Brown algae—it’s called aureoumbra—in Mosquito Lagoon. Plus, we have structural problems that have wrecked the way water flows naturally in Florida. Four straight years of record hot temperatures just act as an accelerant.”

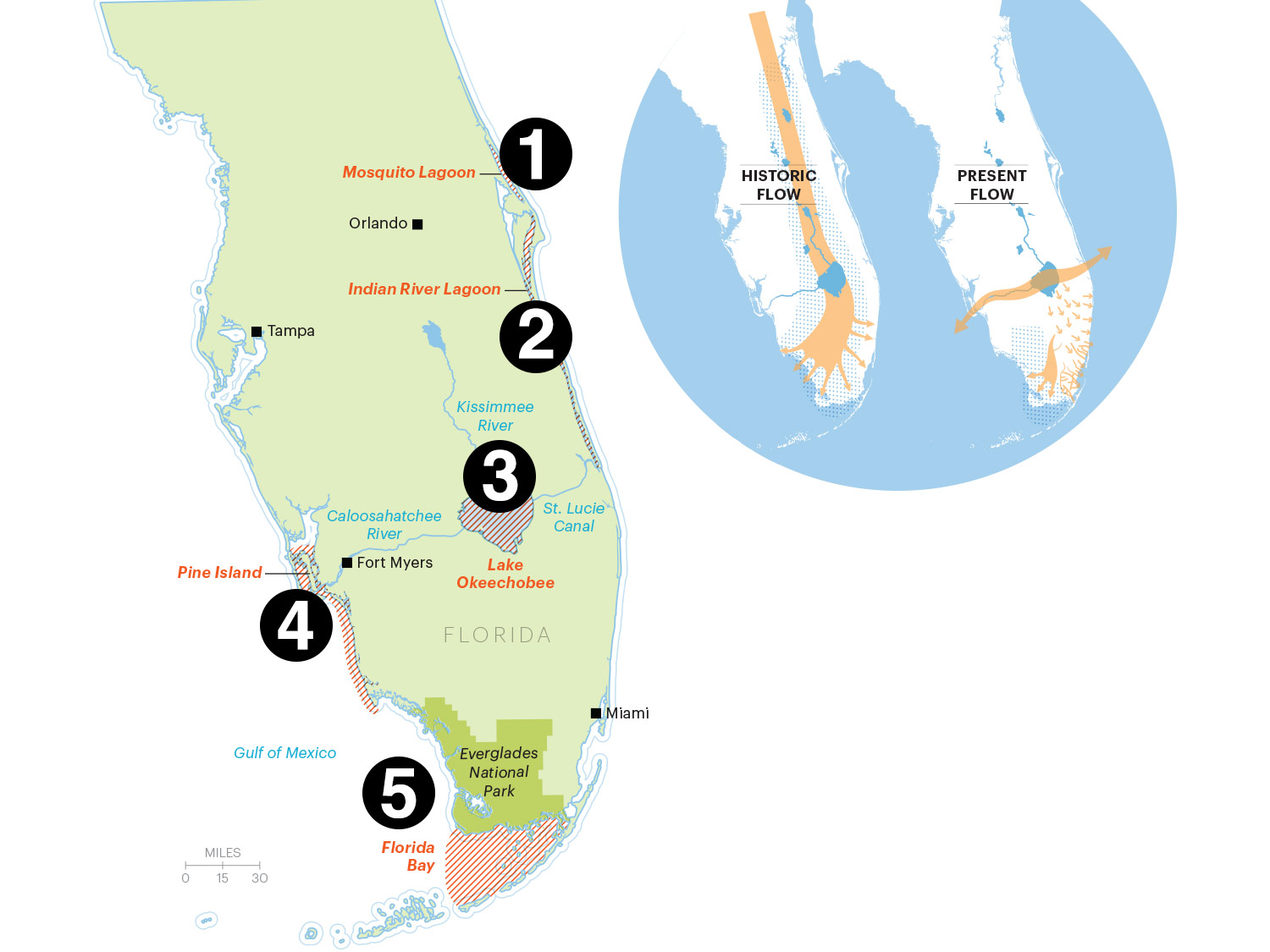

In order to make sense of Gibson’s gloomy perspective on the state, it’s useful to take a big step back in both time and viewpoint. Seen from the distance of space—or a map—Florida is defined by water. A peninsula stabbing through both the globe’s temperate and tropical zones, the abundance and diversity of coastal estuary habitat is what earned Florida its title as the sportfishing capital of the world.

Florida’s appeal has been the easy availability of a variety of species, whether you cast off bridges and piers, book a bluewater charter, or kayak sea-grass flats. If you wanted to catch a speckled seatrout or redfish, baby tarpon or snook, Florida’s East coast and Gulf Coast estuaries were your destinations. Snapper, reds, and bonefish were bread-and-butter species in Florida Bay, and Gulf Coast anglers could consistently catch groupers, mackerel, wahoo, tuna, and sharks.

A robust economy of charter captains, marinas, bait shops, fish camps, and boat dealers grew around the kept promise of good fishing, no matter the season or the method.

But a natural system reliant on water is only as healthy as the components that fuel it. The recent decline in hydrology of the state has given water-policy advocates like Gibson plenty of work to do, and it’s also given charter captains like Rotne plenty to fret about.

River of Grass

Prior to Walt Disney’s developments, rain that fell on Orlando would have found its way into the lazy, meandering Kissimmee River, and after pushing through marshes and shallow reed flats, into massive Lake Okeechobee. From above, the lake looks heart-shaped, but in its natural state it functioned more like a giant liver. Its tens of thousands of acres of shallow grass filtered nutrient-poor water that mainly seeped southward, through the Everglades and eventually into Florida Bay. A fraction of the lake’s fresh water shunted westward through the Caloosahatchee River toward Fort Myers on the Gulf Coast.

On the Atlantic Coast, fertile estuaries like Mosquito Lagoon and the 156-mile-long Indian River Lagoon buffered the mainland from hurricanes and tidal surges, and provided shallow nursery habitat for inshore fish species. Fresh water rarely made it into these estuaries because few interior streams punch through the hard-sand ridges that parallel the coast.

But over the last two generations, Florida has added 17 million residents and undergone landscape-level development. Swampland was drained to make way for oranges, sugarcane, and cattle. The Kissimmee River was straightened to run faster, with far fewer sediment-dropping meanders. A dike was built around Lake Okeechobee to raise its level, and to stop the seep of its water across land to the south, which was then drained and developed for industrial-scale agriculture. Other land was cleared and raised for residential development, which included leak-prone septic tanks. Orlando was paved. Coastlines were stabilized to accommodate high-rise condos, which diminished the barrier islands’ ability to buffer tidal surges.

But the most significant alteration of Florida’s hydrology is the St. Lucie Canal, which was started a full century ago.

Encouraged by economic boosters and delved by Depression-era labor, engineers cut a canal straight across the state, connecting the Atlantic and Gulf coasts with Lake Okeechobee—Lake O or Big O, as it’s called by locals. The St. Lucie Canal enables barges and fishing boats to cross the state without going around the tip of the peninsula, saving hundreds of miles and untold gallons of fuel.

But the canal serves another purpose: to divert fresh water from Lake O during periods of high precipitation. Last year, as water managers tried to keep Okeechobee from topping dikes, the Corps of Engineers released 1.2 billion gallons of fresh water a day down the St. Lucie Canal and into Indian River Lagoon.

The discharge’s lack of salinity is problematic for the marine estuary and its inhabitants, but the canal delivers another, far more troublesome product to the coast: a biohazard in the form of toxic algae. Over the years, as the Lake Okeechobee watershed has been developed, nitrogen and phosphorus levels have spiked in the lake’s historically nutrient-poor water, thanks to upstream septic and agriculture discharges and runoff from lawns and parking lots. When the water warms, the nutrients feed algal blooms that have turned Big O’s water a shimmering green through the summer months. The discharge of fresh water and algal growth has killed thousands of acres of sea grass in lower St. Lucie River and Indian River Lagoon. As the marine plants die, they sink to the bottom and contribute to a layer of lifeless muck.

The algal bloom is also problematic for humans. Commonly called blue-green algae, the organism is actually a photosynthesized bacteria called cyanobacteria that can cause liver and kidney damage. Cyanobacteria explodes when it encounters sewage in the estuaries from leaking septic tanks—the worst blooms hit on hot, sunny days.

Sea Grass ICU

After Mosquito Lagoon and Rotne’s medical nonemergency, my next stop is Stuart, Florida, about 140 miles down the coast. I’ve heard about the work of Zack Jud, director of education at the Florida Oceanographic Institute, and I want his take on the changing ecosystems of Florida’s estuaries.

I find him tending a row of vats with garden hoses threaded through each tub. Inside are flats of juvenile sea grass, tender as bean sprouts as they wave in the weak current, waiting to be planted in the grassless flats of Indian River Lagoon.

Jud acknowledges that sea-grass restoration is a small-scale Band-Aid, but the native vegetation is such a foundational part of the ecosystem that any bit helps, he says, even if it’s propagated in his makeshift nursery.

“Estuaries are resilient,” he says. “If we had six months without freshwater discharges or hurricanes, you’d see functional habitats start to heal themselves. The problem is we haven’t given them any time to reset.”

The solution to southern Florida’s water crisis, Jud says, is allowing Lake O’s water to reach the Everglades and Florida Bay. But, he says, it can’t be the hyper-rich water that’s currently being sluiced down the St. Lucie. One potential solution is a series of storage impoundments south of Okeechobee that would filter water, then release it through the Everglades.

That plan is officially called the Everglades Agricultural Area Storage Reservoir Project, and it would hold and treat 240,000 acre-feet of water. The estimated cost is $1.3 billion—a hefty sum that will be split by the state and federal governments, at least in theory. President Trump toured the Big O in March, just after I had visited, and said he was committed to supporting the project. Florida legislators are asking the President for $200 million a year to fund Everglades projects, but Trump’s initial budget included only $63 million.

“What’s at stake? Right here where we’re standing, a world-class fishery is at stake,” Jud says. “The world-record seatrout was caught 20 miles from here. But big picture, it’s the economy of clean water that drives Florida that’s at stake.”

Sportfishing drives an $8 billion economy in the state that depends on clean water, but the plan is opposed by sugar producers, who might lose land to the project and who are the primary beneficiaries of the discharge system that’s in place now. The current water regime has created near-perfect sugarcane growing conditions in what was formerly swampland. Between 1994 and 2016, the sugar industry poured $57.8 million into state and local political campaigns, according to a review of election records by the Miami Herald and Tampa Bay Times.

But even those within the sportfishing community have different opinions about how to fix the problem. Scott Martin—whose father, the legendary bass angler Roland Martin, founded the biggest fishing resort on Lake O—worries that another reservoir will simply fill up and overflow. He’d rather see the impoundment funds used to restore Lake O’s shoreline marshes to filter water that would then be discharged to the coasts.

“People talk about turning the Everglades into the way they were 80 years ago,” says Martin, who manages the resort. “It’s just not gonna happen. So, let’s fix what we can.”

Creature from the Black-Mayonnaise Lagoon

After I leave Lake Okeechobee, I take a seat on Capt. Mike Connors’ 17-foot Action Craft. I want to see for myself the effect of this wash of nutrient-laden fresh water on what’s historically been a go-to speckled trout fishery in Indian River Lagoon.

It’s the fullest moon of the spring, and the tidal push combined with a strafing wind make for tough fishing. So we tuck into one of the more sheltered coves of the St. Lucie River. We’re just a few miles below the outlet structure of the St. Lucie Canal, which Connors calls “the gates of hell” for the environmental jihad inflicted on the estuary habitat when they open.

“Scientists term this ‘flocculant ooze,’ but I prefer to call it ‘black mayonnaise,’ ” Connors says as he lifts his electric push-pole anchor to reveal a viscous coating of sinister black paste. It smells exactly how you think it would.

“The entire bottom of the St. Lucie is covered with this,” Connors says as he cinches a hand-tied shrimp pattern onto the leader of my 9-weight rod. “It is anaerobic and lifeless, and averages between a foot and 2 feet deep. And it’s totally because of freshwater discharge.” As I cast toward the jungle-dense mangrove shore, hoping for the take of a snook or a black drum or a jack crevalle—and hoping just as earnestly to avoid dredging up more black mayonnaise—Connors describes the changes of the estuary.

Read Next: Searching the Florida Everglades for Giant Pythons

“When I moved to Stuart in 2000, it was nothing to have a 50-fish day on trout, and a good number of gators [fish over about 6 pounds],” Connors says. “I’d wade-fish out on what’s called Sailfish Flats in Indian River Lagoon, and sometimes you’d get your legs so tangled in the thick sea grass that if you weren’t careful, you’d fall on your face. Trout depend on that grass. All these flats used to be dark. That was the grass. Now they’re white like bonefish flats. The turtle grass and manatee grass disappeared over a 10-year period. Why? Sea grass can’t live in fresh water.”

As Connors talks, I make a cast tight to the mangroves, twitch my fly, and feel the take. It’s a big, slashing fish, and it spools me almost to my backing as it heads for the open water of the lagoon. Connors follows in the boat, allowing me to regain some line. As I try to turn the fish’s head toward the boat, I look up. A wall of banana-leaf mangroves rises out of the water behind me. In front, million-dollar waterfront homes sparkle in the spring light. I’m between primordial Florida and developed Florida, tied to a fish that has a place in both worlds.

I bring the fish to the surface and then duel it to the boat. Connors whoops. It’s a giant snook, its black lateral line slashing through the coffee-colored water. We take photos, admire the fish, then slip it back into the water.

“Get outta here!” Connors yells after the tailing swirl. “Get out of here before they open the gates of hell!”

1. Mosquito Lagoon

Problem: Fecal contamination, sea-grass depletion Solution: Fund rural sewer systems and manage power-plant discharges

2. Indian River Lagoon

Problem: Toxic cyanobacteria contamination Solution: Slow freshwater discharges from Lake O, via St. Lucie Canal

3. Lake okeechobee

Problem: Excessive runoff, high water levels and nitrogen contamination Solution: Clean and restore Kissimmee River, repair Hoover Dike, build new storage reservoir

4. Pine Island

Problem: Algal contamination, frequent and unnatural estuary discharges Solution: Store and clean Lake O runoff, manage releases during dry season

5. Florida bay

Problem: Sea-grass depletion caused by hypersalinity, contaminated runoff Solution: Return historic flows from Lake O through the Everglades