Ever since Chronic Wasting Disease reared its ugly head, deer hunters nationwide have wondered what, if anything, can be done to stop its spread? Biologists and wildlife managers are making strides. The results of ongoing research and analysis is offering a glimpse into not only the makeup of CWD, but also potential ways to keep it from spreading.

Here are some facts about the disease, it’s current range, and how you can help prevent it from infecting deer where you hunt.

CWD Continues to Creep

Free-ranging cervids in 23 states have tested positive for CWD, but Wisconsin has weathered the disease the longest (since 2002). The state started with an aggressive containment strategy—essentially trying to kill every deer within a CWD eradication zone—but after resistance from hunters and landowners, it transitioned to a monitoring program. The result? CWD continued to spread.

Of the 72 counties in Wisconsin, 55 are now classified as CWD-affected. Last year, the number of CWD-affected counties was 44. The CWD prevalence rate in Wisconsin, or the estimated percentage of the population carrying CWD pathogens, is close to 10 percent, and in some counties, the prevalence rate in adult bucks is above 40 percent.

Meanwhile, the CWD prevalence rate in Illinois is closer to 2 percent. The reason could be a more aggressive approach to containment. Since 2003, Illinois has employed sharpshooters and drastically increased harvest quotas to reduce deer populations around CWD-positive locations.

Hunters Can Help Manage CWD

CWD has been found in fewer than 9 percent of jurisdictions in the U.S. That means residents of the other 91 percent can avoid the CWD problem. Here’s how.

A. Find out if the area where you hunt is CWD-positive. Visit the CWD Alliance (cwd-info.org) and click on the national map or state-specific links. If you subscribe to onX Hunt, click on the CWD layer.

B. Work to keep CWD out of your area. If you travel to hunt a CWD-positive area, submit every animal you kill for testing. Follow all carcass-transport rules, and do not eat any venison until you receive results of the CWD test. Never dispose of any part of a deer or elk from a CWD-infected area anywhere but an approved sanitary landfill. And if you hunt near a CWD area, voluntarily submit your deer for testing.

C. Report any sick or disoriented deer to the state wildlife agency. If you see someone illegally transporting whole carcasses of dead deer or any live deer, notify law enforcement immediately.

D. Reconsider your use of deer urine as a cover scent or lure. Use products approved by the Archery Trade Association’s Deer Protection Program (look for the blue ATA checkmark), which requires producers to adhere to stringent guidelines to reduce the risk of spreading CWD through infected urine.

CWD Testing is Complex

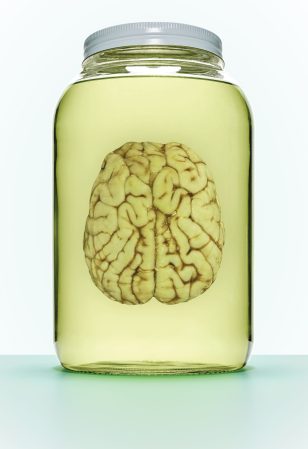

The biggest challenge for CWD testing? The animal must be dead, and recently dead at that. Because the infected prions are concentrated in the animal’s brain and lymphatic tissue, most tests begin with dissecting the brain stem.

Game agencies that solicit deer and elk heads for CWD generally pay for the testing, which can run about $80 per deer. And because samples are generally sent away to a diagnostic lab for testing, results take a couple of weeks to process and report. Individual hunters can submit samples if they’re uncertain about the health of a deer they kill. Check with your state’s wildlife agency for details about how to remove lymph nodes and how to submit them for testing.

Researchers have been studying alternatives that would allow hunters and game farmers to get test results more quickly and with less effort than a full-on brain dissection. A rectal-biopsy test can be used in limited cases, mostly large-scale game farms, to detect CWD in live cervids, but it’s expensive and time-consuming. And a blood-swipe test that would allow hunters to collect samples of dead deer in the field has promise, but researchers are still evaluating its viability.

Read Next: The Fight to Stop the Spread of Chronic Wasting Disease

CWD is Much Different Than EHD

Why worry about CWD when EHD kills more deer faster?

EHD, or epizootic hemorrhagic disease, sometimes called “blue tongue,” typically surfaces at the end of a hot, dry summer, and is spread by midges. Deer that get EHD tend to die quickly—in large numbers all at once—and often near water sources.

Higher densities of whitetails combined with warmer, drier summers have accelerated the frequency and severity of EHD outbreaks.

CWD, meanwhile, is a more cryptic killer. Its victims often die as a result of secondary causes: vehicle collisions or predation. Deer can carry CWD for years before its symptoms are visible, but because the infectious agents are shed in the environment, a single deer can infect others for years after the host has died.

While there are no ready cures for either malady, deer populations typically build resistance to EHD, so that mortality decreases with each subsequent exposure. CWD, on the other hand, is always fatal, and there’s no indication that individuals develop a resistance.